Scott AndersonEzekiel 34:11-24 † Psalm 100 † Ephesians 1:15-23 † Matthew 25:31-46

A video version of this meditation can be found here. It’s all hindsight. All of it. No one was doing what they were doing in the story because they thought they were doing it “unto Christ.” They were just doing it. The surprise was that it was, or that it is the Holy One in those who were vulnerable. And everyone was surprised!. Everyone was surprised that this would be the thing that would set them apart—right from left, sheep from goats. When did we see you hungry or thirsty, or a stranger or with no clothes on your back, or locked up?

0 Comments

Scott AndersonDeuteronomy 34:1-12 † Psalm 90:1-6, 13-17 † 1 Thessalonians 2:1-8 † Matthew 22:34-46

Back in 2000 my daughter Claire and I went camping with a dear friend and his daughter. The next year another dear college friend and his daughters joined us. Soon enough, my son Peter was old enough and he started coming, building what became a summer camping tradition that lasted some 15 years—essentially through the school years of all our kids. The annual July drive to our camping trip in Mount Rainier National Park was always a highlight of the year. We hiked all through the park and in nearby locations. We celebrated meals together and spent long hours in conversation around the fire. We created memories that shaped us and will outlast my lifetime. The kids are older now. Half of them are married and have started their own families. There was one year, one conversation I was reminded of this week. We had been going to the same campground—Ohanapecosh in the Southeast corner of the Park—for at least a decade and we dads began to wonder if we ought to change it up a bit. So we proposed the idea of a new location, a new adventure for the following year to the kids. Before we could even finish the sentence, and with one voice they all cried out: “No! It’s tradition!” Now, let me try to explain the impact of this on me in the moment. Scott AndersonActs 2:14a, 36-41 † Psalm 116:1-4, 12-19 † 1 Peter 1:17-23 † Luke 24:13-35 For over 1400 days—nearly four years—between 1992 and 1996, the city of Sarajevo was under siege. One study of the survivors found that many had developed a super-heightened sense of spatial awareness—a skill for evading bullets or bombs, a skill that they carried with them throughout their lives. “People, during times of prolonged, radical change, end up changing,” said the study’s author[i] in an article this week that takes an early run at how we might be changed on the other side of this pandemic. It makes sense. We are an adaptable species. We grow and change according to requirements on the ground, in the environment, or just at home in these times. Not surprisingly, studies from previous outbreaks—SARS, Ebola and swine flu—showed almost universal spikes in anxiety, depression and anger. But they also found that people acted to regain a sense of autonomy and control. People worked on their diet. They read more news. They made art. Who knows, maybe they made masks. You may remember those Sarajevo roses we showed you some months ago in the “before times.” Scott AndersonJeremiah 31:16 † Psalm 118:1-2, 14-24 † Acts 1:34-43 † Matthew 28:1-10

Two phrases catch my attention in these days of pandemic and social isolating. Two phrases seem especially relevant as we find ourselves a month into a disruptive reality most of us have never experienced before. The first is this: “Do not be afraid.” It is the message given by the angel—an other-worldly being who apparently looks like lightning in a jacket of snow and shows up just as a massive earthquake hits. Just to the side you have a couple of military guards laying there, by all appearances dead. I mean, the advice sounds a little unnecessary, doesn’t it? What could they possible be afraid of? Scott AndersonProverbs 8:1-31 † Psalm 8 † Romans 5:1-5 † John 16:12-15

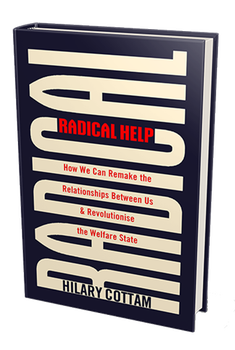

I suspect our children understand far better than we do the implications of climate change on the future. It is, after all, their future, although we are the ones who have given it to them, such as it is. So let me offer you one simple illustration that caught my attention recently. Most of us are likely aware that populism is not simply an American phenomenon. We have a president who has made a decisively inward turn, advocating for walls and putting things in terms of insiders and outsiders both within and without our country. But we are not the only country where these explosive political dynamics have found new life. There is something of an international battle going on for the soul of our lives whether its arguments over Brexit in the UK, or Yellow Vest protests in France. These are all, at their roots, populist movements, that is, they are in revolt against elites, both in an economic as well as a political sense. Scott Anderson This is Hilary Cottam in a TED talk from 2015.[i] She’s a social entrepreneur whose been thinking much of her life about how we solve some of these deep and complex social problems that have been perplexing us for some time now. She has a new book out, called Radical Help[ii] that takes a deep dive into the welfare state and how we might remake it. As you can tell, she’s doing her work in Great Britain, and has spent most of her life in Europe and Africa exploring these questions. But I think her work speaks to our own experience in the states as well, and to the needs for many of our institutions to adapt to changing realities. In her presentation, Cottam goes on to provide a pretty stark picture of how the system as it currently is does not serve Ella well or others in similar circumstances, but may, in fact, work to keep them imprisoned in a cycle of despair, even as the people and the institutions they serve were and continue to be well-intentioned. Scott AndersonDeuteronomy 26:1-11 † Psalm 91:1-2, 9-16 † Romans 10:8b-13 † Luke 4:1-13

Possession is nine-tenths of the law. No doubt you’ve heard this adage that suggests that if you possess something, you have a stronger legal claim to owning it than someone who merely says they own it. The doctrine allowed Floyd Hatfield to retain possession of the pig that the McCoys claimed was their property, although we can imagine it didn’t make their lives better or help to de-escalate the historic dispute between the Hatfields and McCoys. The old saw has underlined feuds on too many school playgrounds to count. It has destroyed countless friendships. It has been front and center in disputes in U.S. history with tragic results for many of the early dwellers of these lands. It has contributed to the fire between Palestinians and Israelis, and all of their proxies, and in too many stories to tell on every continent throughout every age. The question of ownership and land is arguably at the root of every conflict, all human violence, and the climate change peril that our planet and its inhabitants are facing. So it may interest us to note that this is something of a theme in the telling of our scriptures today. Scott AndersonJeremiah 17:5-10 † Psalm 1 † 1 Corinthians 15:12-20 † Luke 6:17-26

As I was studying our texts for today, I found myself rooting around for a way to understand blessing as it is portrayed in Luke from Jesus: Blessed are you who are poor. Blessed are you who are hungry now. Blessed are you who weep now. God is on your side. But the more I tried to unpack this idea, the more I tried to understand how really this translates into blessing, the more stuck I got. How is it a blessing to be hungry now even if you’ll get something later? How is it blessing to weep now, simply for the promise of a laugh later? Sure, there are some ways to get at this, but they are problematic, too often approaching some twisted endorsement for suffering or persecution. And how is the promise of the Kingdom a blessing now for a poor one who has nothing and is in danger? If I’m honest, I have to admit I don’t know the answer. I really don’t know how to understand this idea of blessing. I don’t understand how it is a blessing to be poor and to go without and to live on the edges of society. I don’t see it. I wish I did, but I don’t. Perhaps you do. Given that, I’ve realized I’m not in a position to unpack this first part of the passage in Luke that is blunt and gritty and material and so much in contrast to the ethereal “blessed are the poor in spirit” that Jesus proclaims in Matthew.[i] At least part of the problem, if not all, of course, is that I’m not poor. How should I expect to understand something I haven’t experienced—especially something as hard as this? And the fact is, most, if not all of us, by objective standards are not poor. If we measure ourselves and our wealth and well-being through the arc of history, this is abundantly clear. We have access to food and the basic resources needed for survival in far greater quantity and more reliably than previous generations and even more so than our pre-modern ancestors. And even if we measure ourselves in comparison to the world population as it is today, it is difficult to argue we are poor by any standard. Scott AndersonNehemiah 8:1-3, 5-6, 8-10 † Psalm 19 † 1 Corinthians 12:12-31a † Luke 4:14-21

You’ve probably heard the one about lies and statistics. It’s a quote from Mark Twain, from about 1906 that he attributed to the British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli. Rather than repeat it here, let me just defer to a less colorful paraphrase of it from a letter to the editor of the British newspaper the National Observer: “Sir, —It has been wittily remarked that there are three kinds of falsehood: the first is a ‘fib,’ the second is a downright lie, and the third and most aggravated is statistics.”[I] Anyway, I found myself thinking about this, and about statistics in particular, as I was preparing for today, and trying to get a sense of what Luke is trying to claim about Jesus and his work in this text. Jesus stands up among his hometown folk and reads from Isaiah: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me,” And then the rest of it reads like a mission statement, which is, I think, Luke’s purpose. This, Luke suggests, is what Jesus is up to, what he is about, what God is doing in this promised one of unprecedented power and truth. “He has anointed me,” Jesus reads, to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”[ii] The passage is plain, and the work is straightforward, although it may take a little unpacking. But Old Testament scholar Walter Brueggemann, in his recent book Tenacious Solidarity is concerned that we may miss the plain sense of the text. Here’s why. He says: “we have been schooled, for a variety of reasons, to read the Bible in categories that are individualistic, privatistic, other-worldly, and “spiritual.”[iii] Now, he is getting old. Perhaps he’s worried about what he sees, as he nears the twilight of his long career and his life. But he makes a compelling case that we are prone to step away from the plain meaning of this gospel to our peril. Scott AndersonIsaiah 62:1-5 † Psalm 36:5-10 † 1 Corinthians 12:1-11 † John 2:1-11

So what is going on here? Is this a story about a wedding that hasn’t been planned very well, a potential social disaster, a mother and son bickering because they don’t want their friends to be embarrassed? It could be. “Woman”--mother, why are you asking me. It’s not my time. And yet, apparently it is. Jesus’ objection seems to drown in the flow of the story as water jars are quickly filled, as an oblivious steward is astounded, and as a wedding is saved with about 400 bottles of really good wine no one accounted for. Or maybe it’s not that at all. Maybe the party wasn’t about to collapse. Maybe this wasn’t about poor planning. It could have been even worse: a story about a poor, struggling family doing their best to pull off a celebration demanded by social customs that they could not afford. Suddenly this gift not only saves the day, but delivers them from shame. Or, it could be that this was a celebration that was simply winding down: “When the wine had run out,” the story goes, as if this was the expectation, as if there was an understanding that all good celebrations have a closing time. If we read it that way, this becomes gratuitous. A story about abundance for the sake of abundance—unnecessary, saving nothing, a sign, as John tells us, the “first of his signs” of a story and a savior that is so full of life that nothing will be able to hold it back—not powers or principalities, armies or political leaders. Gratuitousness, generosity, an onslaught of extravagance. There are many ways we could read this. The story does not seem to tip its hand. This is a sign—the first of his signs, says the text. But a sign of what? What do the disciples see that makes them believe in him and sets this greater story in motion? |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed