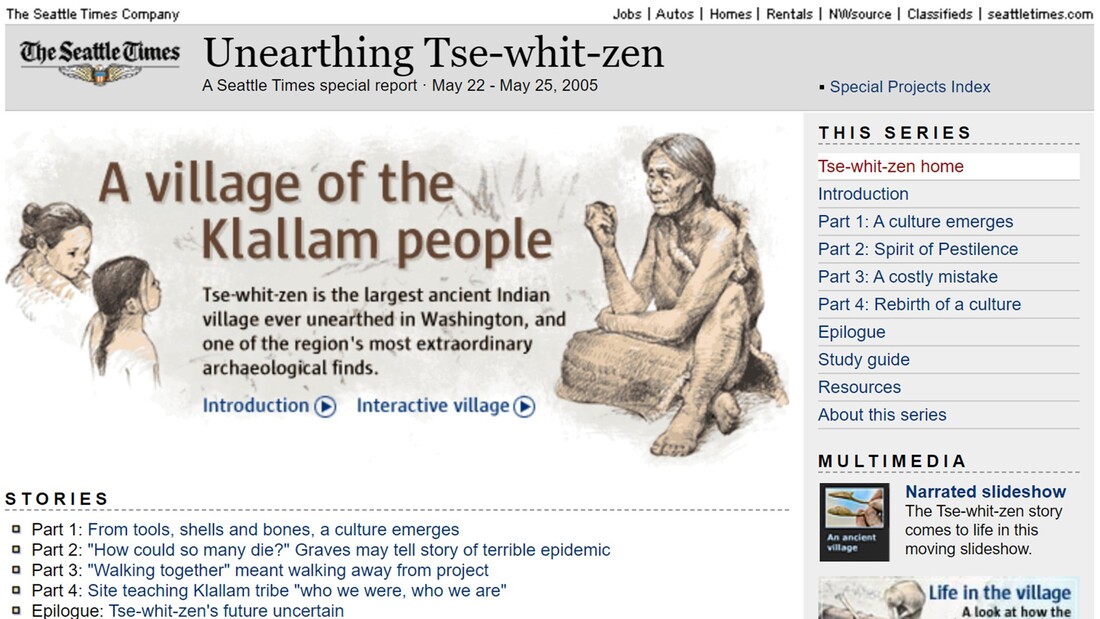

Scott AndersonEzekiel 34:11-24 † Psalm 100 † Ephesians 1:15-23 † Matthew 25:31-46 A video version of this meditation can be found here. It’s all hindsight. All of it. No one was doing what they were doing in the story because they thought they were doing it “unto Christ.” They were just doing it. The surprise was that it was, or that it is the Holy One in those who were vulnerable. And everyone was surprised!. Everyone was surprised that this would be the thing that would set them apart—right from left, sheep from goats. When did we see you hungry or thirsty, or a stranger or with no clothes on your back, or locked up? Which kind of begs the question. What were they expecting? Not so much for the goats. We know all-too-well the world in which people do “goaty” things, do for themselves, vote for their own interests or power, look out for number one, shove and claw and occupy and foul more space than they need to. This story is as old as the hills, or at least as old as Ezekiel who sounds like a modern-day prophet for climate change. “Is it not enough,” the prophet asks, for you to feed on the good pasture, but you must tread down with your feet the rest of your pasture? When you drink of clear water, must you foul the rest with your feet? And must my sheep eat what you have trodden with your feet, and drink what you have fouled with your feet?[i] The text reminds me of the difference between bison and cattle on their impact to vulnerable streams and water sources. And it reminds me that a big reason we have so many cattle and so few bison was that the US government supported their extermination as a way of driving indigenous tribes from the land that European settlers wanted for themselves. Why do we claw and fight and try to deny what others are due when there is more than enough to go around? The truth, I suspect, is that we all have a little sheep and a little goat in us—we all have contested space within us, a DMZ between Thanksgiving generosity—at a REACH meal, say, or in support of Honey Dew families, or in our embrace of those we choose to call family—and that feeding-frenzy we call Black Friday or white privilege or unjust tax structures or stolen elections. But they were all surprised—sheep and goats together. No one was expecting this. It just kind of surfaced. So if it wasn’t about pleasing, about caring, about serving as a way to meet the holy, to do it “unto Christ,” what was the motivation? Why did they do it? What did it mean? What does it say—about us? I don’t know about you, but I think for me, when I live up to my best self, when I put others before myself, when I take time to leave the place better than when I found it, I do it because I am convinced it makes it better for everyone, including me. There’s self-serving in the food line. There’s healing to be found with the sick. There’s freedom to be gained when I sit behind bars with someone who is locked up. Resilience rubs off, I suspect, when you march with people who have miles of advocacy under their belts. You become thankful when you hang out with thankful people. There’s peace and contentment in a country and a world order that works for everyone. “A lot of spiritual energy is stored in these places: loneliness, silence and fear,” according to the contemplative writer Richard Rohr. “You can find that energy by going there and staying there.”[ii] The inverse is also true. When you tend not to occupy those places, you can lose a lot. You can even lose yourself. When you don’t pay attention to what’s around you, you not only do damage to your surroundings, but you set yourself up for far worse. When a backhoe operator on the Port Angeles waterfront dug up some bones in 2003, journalist Linda Mapes was sent by the Seattle Times to cover the story. Excitement at a once-in-a-generation archaeological find quickly grew as 12,000 year-old artifacts were uncovered. It turned out that the site chosen for a massive dry dock to construct badly needed replacement pontoons for the Hood Canal Bridge was the site of Tse-whit-zen Village, the long-buried homeland of the Klallam people. But the excitement soon gave way to anguish as tribal members working alongside state construction workers encountered more and more human remains, including numerous intact burials. Couples buried next to one another, one hand in the other. The remains of children and the elderly shared what turned out to be an ancient burial ground that the state had selected for a construction site. Finally, tribal members said enough. And the project into which they had sunk 90 million dollars was stopped cold. The state, in a decision that was unprecedented, agreed to find a new site and start over. Mapes, the Seattle Times journalist, tells the story in her book Breaking Ground.[iii] And one of the things you discover pretty quickly is that it was no surprise. At least it shouldn’t have been. The village name Tse-whit-zen is translated “area inside the spit.” The ancient village was located in a natural deep-water harbor that protected the land from the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The nine-mile spit was formed as the Elwha River carried sediment 45 miles from the deep snows 8000 feet above and hundreds of inches of rain a year in the rainforest to the south called Sun-a-do by the Duwamish people—what we now know as the Olympic Mountains because some English Captain named John Meares decided to evoke Greek mythology.[iv] “In aboriginal times,” Mapes writes in Breaking Ground, “the river was home to ten different seasonal runs of salmon that fed more than twenty-two species of wildlife as well as the Klallam people.”[v] And now, not only has the village site been preserved, but the dams built on the Elwha in the 1920s have been removed. The river’s clean, cold, clear waters are once again alive with oxygen and nutrients. The salmon are even beginning to return. It was, of course, the perfect site for a village. The Elwha was once home to the mighty June Hog chinook. Some of these fish weighed as much as 100 pounds. These were the biggest salmon in Puget Sound, or should I say the Salish Sea?—its name for millennia until George Vancouver decided to crowd out the memory to honor a Huguenot lieutenant. It was a perfect site for a village. The salt tide still sluices through the cobble on the sand spit of the Ediz Hook, smoothing and rounding beach stones that fit just so in the hand. Just the right size to chip into a knife to butcher the salmon that surged by here. The tide flats along the waterfront were alive with geoducks, oysters, mussels, and clams. The Elwha watershed provided a pantry of foods that ensured the people had something to eat in every season. While our European ancestors were fighting wars with guns and ships and knives, the Klallam people fought wars with potlatches in which, during the winter season, the richest members of the tribe earned status by hosting lavish feasts and heaping presents on their guests in week-long celebrations devoted to feasting, dancing, singing, and gift-giving. Mapes explains,

The salmon mentored the Klallam people, informing a culture that mirrored the ways of the Klallam’s signature fish. Like the salmon, the Klallams showed their wealth by gifting and did not waste or hoard the largesse of the river, sea, mountains, and meadows that sustained their lives.”[vi] Of course, it was a village before it was the town of Port Angeles and the site for a deep-water dry-dock. Native people used it continuously long before the time of Jesus, and before the development of the English language. But when the Washington State Department of Transportation showed up to scout a location for its construction project, the waterfront site offered by city business and political leaders wasn’t known as an Indigenous anything. Instead it was understood as, valued as, and sold to the state as prime industrial land. The thing is they didn’t ask. They didn’t ask Adeline Smith and Bea Charles, Lower Elwha Klallam elders who could tell anyone just what was under this industrialized waterfront. Nobody asked. And more than likely they knew; they just didn’t want to remember what they had fouled under their feet. But the earth did not forget. The land cannot be kept silent forever. The right and the left would be sorted. This is one truth of this day that we call Christ the King, or the Reign of Christ. God’s justice will win out. Indeed, it breaks in time and again in our time. Something to be thankful for and mindful of. But it is the way it breaks through that is most astonishing. Gerald Bruce Miller, of the Yakama tribe is quoted at the beginning of Breaking Ground: In the early days of my grandfather, there was an ancient law. It was to keep the knowledge and memories of our ancestors alive. If a person did not do this, they would become poor, destitute, have no past or identity… They would have no foundation in their lives. They would have to borrow someone else’s culture. This was a truly sad state of affairs for a people to endure, for they would have no resiliency.[vii] If we visit our siblings who are locked up or sick or if we feed our neighbors who are hungry and thirsty, and if we house our friends who have no home for no other reason, we should do so in order to be more resilient, in order to have a foundation, in order to remember who we are and not lose ourselves or our future in whatever we choose to forget. If we visit our siblings in prison, or sit bedside or Zoom-side keeping company with the sick, if we share a meal with someone who is hungry and thirsty, and if we build houses and partner with our friends who have been historically redlined and denied home loans to listen for sustainable solutions for no other reason, we should do so because in them we meet the Holy One we know as Christ our King, the presence of love and justice and peace that reminds us of the glory of what we, together are. This is, at least, a good place to start. And perhaps it gets us to that better place where we can, like the Ephesians, be fully awake to God’s goodness, be awake to the presence of Christ in these we serve, and be awake to the presence of love that meets us there, that speaks to us of the abundance we have to share, that has the power to heal and save us. Amen. Notes: [i] Ezekiel 34:18-19. [ii] Rohr, Richard; Martos, Joseph (2011-07-07). From Wild Man to Wise Man: Reflections on Male Spirituality (p. 114). . Kindle Edition. [iii] Mapes, Linda V. Breaking Ground: The Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe and the Unearthing of Tse-whit-zen Village (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2009). [iv] See the Wikipedia entry “Olympic Mountains”. Retrieved on November 16, 2020 from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olympic_Mountains. [v] Mapes, Linda V. Breaking Ground: The Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe and the Unearthing of Tse-whit-zen Village (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2009), 26. [vi] Ibid., 27. [vii] Ibid., p. vii.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed