Scott Anderson1 Samuel 1:4-20 † 1 Samuel 2:1-10 † Hebrews 10:11-14, 19-25 † Mark 13:1-8 You can view a video of the service and sermon here. Franz Dolp was a professor of economics at Oregon State University when he began, perhaps, the greatest work of his life. As a young father and professor, his marriage had eroded, and his dream of creating an Oregon homestead with it. When he drove away from the farm intended for “till death do us part,” it was with the good-bye blessing, “I hope that your next dream turns out better than your last.”[i] He eventually found his way to forty acres on Shotpouch Creek. This logged-out, chaotic hot mess of vine maples, leggy hardwoods, and thorns was in the same Oregon coast mountains where his grandfather had made a hardscrabble homestead. In his journal, Franz wrote that he had “made the mistake of visiting the farm after it was sold. The new owners had cut it all.” I sat among the stumps and the swirling red dust, and I cried. When I moved to Shotpouch after leaving the farm, I realized that making a new home required more than building a cabin or planting an apple tree. It required some healing for me and for the land.”[ii] “My work [at Shotpouch] grew out of a deeply experienced sense of loss,” he wrote, “the loss of what should be here.”[iii] Robin Wall Kimmerer tells the story of how Franz Dolp, a wounded man, moved to live on wounded land at Shotpouch Creek in her book Braiding Sweetgrass, in a chapter she titles “Old Growth Children.” Franz wrote in his journal, “These forty acres were to be my retreat, my escape to the wild. But this was no pristine wilderness.” The land was razed by a series of clear-cuts over the years—first the venerable old-growth forest and then its children. No sooner had the Doug firs grown back than the loggers came for them again.[iv] Everything is different after land is clear-cut. Sunshine is abundant, the soil is broken open and unstable, temperatures rise, the humus blanket gives way to exposed minerals. Forest ecosystems have tools for dealing with disturbances, of course. Early plants get to work on damage control, quickly.

0 Comments

Scott AndersonRuth 3:1-5, 4:13-17 † Psalm 127 † Hebrews 9:24-28 † Mark 12:38-44

You can view a video of the service and sermon here. Robin Wall Kimmerer tells of an ancient ceremonial tradition among the indigenous coastal people in the Northwest. It always happened about this time of the year. If you’ve been out and about on the rivers in the past month or so, paying attention to what’s been happening in our waters, it may not surprise you. Kimmerer spotlights the story this way: Far out beyond the surf they felt it. Beyond the reach of any canoe, half a sea away, something stirred inside them, an ancient clock of bone and blood that said, “It’s time.” Silver-scaled body its own sort of compass needle spinning in the sea, the floating arrow turned toward home. From all directions they came, the sea a funnel of fish, narrowing their path as they gathered closer and closer, until their silver bodies lit up the water, redd-mates sent to sea, prodigal salmon coming home.[i] Scott AndersonIsaiah 25:6-9 † Psalm 24 † Revelation 21:1-6a † John 11:32-44 You can view a video of the service and sermon here. It took me about two minutes the other day to remember the name for these. I could see them in my mind’s eye, and I knew they were in the fridge right next to me, but I was determined to flex those memory muscles and work past this mind block. Every time the words came close to my consciousness, stupid broccoli kept getting in the way. Bru, bru, bru…broccoli.

No! Finally, I got it! I conquered! “Brussel sprouts!” I shouted to Barb who I suspect, by that point, was looking a bit anxious. It was almost as if I had to look out of the periphery of my brain to do it, but I prevailed! Maggie Breen1 Samuel 15:34-16:13 † Psalm 20 † 2 Corinthians 5:6-10, 14-17 † Mark 4:26-34 You can view a video recording of this sermon here.

Isn’t that the case with so much of what we experience? We take something in, and we react, sometimes quietly, sometimes less so, but so often out of these hard-earned unspoken assumptions that have this silent power to affect our lives and the lives of others.

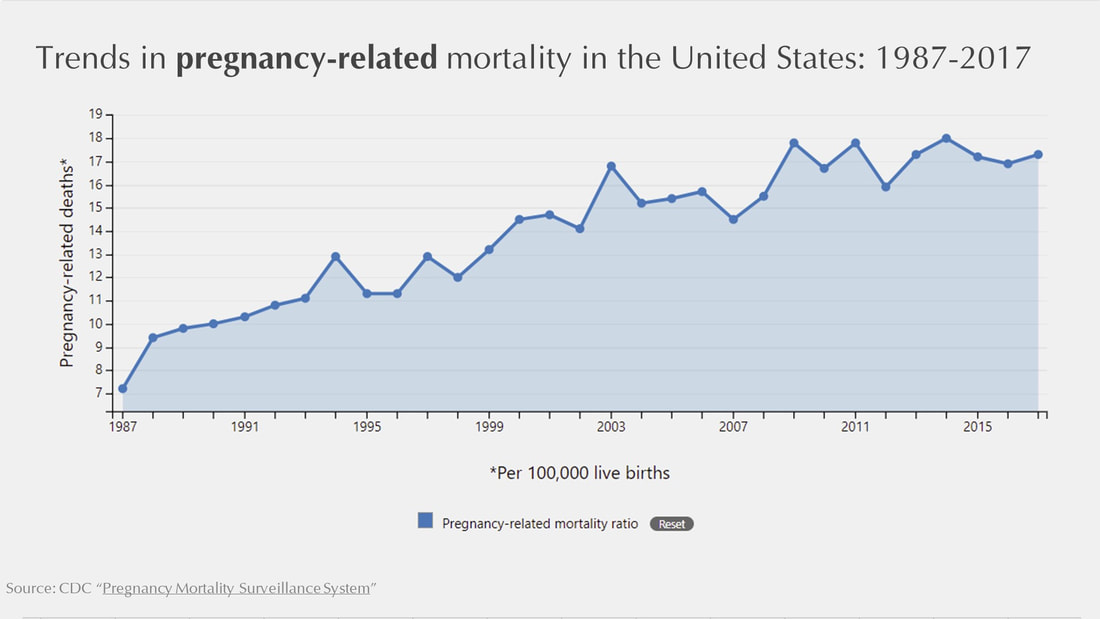

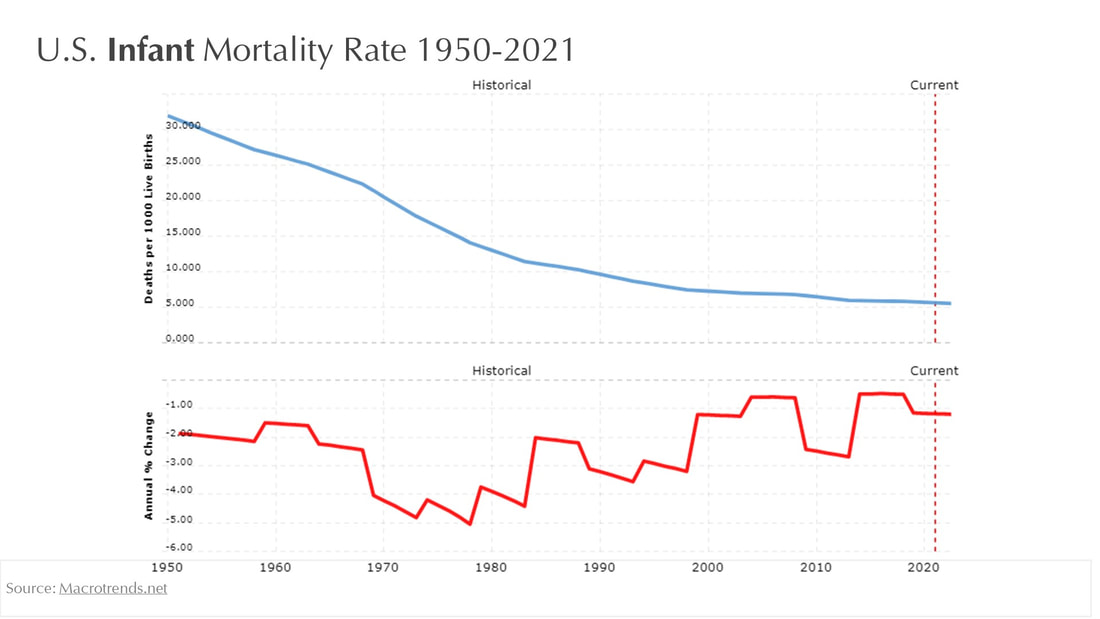

Rosebay Willowherb, for me, used to be a sign of something bad and only something bad. It grew in my family’s yard starting in the late spring and early summer each year. Those stubborn stems with their long, thin, rough, dark green leaves that seemed to me to spiral like a screwdriver or a drill making its way through the low growth. And then as summer moved on those loud pink flowers, one atop the other, clamoring for the sky. And bees, lots of bees, would hang out in that slanting swath of pink and then the flowers would turn to these long thin seed capsules that would split open seemingly overnight to reveal this tangled mess of tiny, almost invisible brown seeds hidden in a mass of silk hairs that would carry them off in clouds. Scott AndersonActs 1:15-17, 21-26 † Psalm 1 † 1 John 5:9-13 † John 17:6-9 A video version of this sermon can be found here. Perhaps you are aware that the US is the only developed country in which pregnancy-related mortality—deaths of women in childbirth—is actually going up rather than down. And while rates of infant mortality have generally gone down over the years, infant mortality remains a big problem among some populations—this in a country that has demonstrated such astonishing scientific capabilities when it comes to things like rapidly developing vaccines in a crisis that we are able to anticipate being back together next week. As of 2020, American women were far more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than women in other wealthy countries.[i] There is an important, and startling caveat to all this, though. These numbers are not trending across the board. Both of these rates are driven by what is going on with Black women and babies.

Scott AndersonJeremiah 31:31-34 † Psalm 119:9-16 † Hebrews 5:5-10 † John 12:20-33

A video version of this sermon can be found here. Unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just a single grain; but if it dies, it bears much fruit. Here is the crux, the turning point of John’s gospel. It marks the major turn in the structure of the book. The hour has indeed come, even though we are only halfway through the gospel. “Now is the judgment of this world; now the ruler of this world will be driven out.”[i] We should not miss this. And if we do not understand, we are wise to listen and open ourselves to it until we do. To accentuate the point, we hear not only the voice of Jesus, but the voice of heaven affirm it. In the other gospels—in Matthew, Mark, and Luke—the voice of God is also heard, but at Jesus’ baptism. In John, it is heard here and here only. “I have glorified it—God’s name, that is—and I will glorify it again.” Why here? And what does it mean? This is a strange affirmation to a strange fruit. Perhaps it seems counterintuitive to believe that death breeds life. We do know, though, the truth of this text so central to our Christian faith. We have seen again and again the power of self-giving and sacrifice. Martyrs through history have given themselves so that life would change for the many. Scott AndersonNumbers 21:4-9 † Psalm 107:1-3, 17-22 † Ephesians 2:1-10 † John 3:14-20

A video version of this sermon can be found here. I’m sure you’ve noted in the news that we have passed another important milestone this week. We have now spent a full year with this pandemic, with its limitations on our movement and interaction with one another. Our last in-person worship was March 8th, 2020. On that date the US had marked 22 deaths from Covid-19. None of us have been unaffected by the strains of this past year. Few of us have been untouched by the sting of death. What would we have thought, what would we have done differently if we knew at that moment that just a year later well over half a million of us would be dead from the disease in the United States and 2.6 million souls world-wide? How would we have acted differently? I suppose we in the Seattle area have a unique perspective on this having been hit first and hardest. I’m sure you’ve seen the article first published in the New York Times noting that had the rest of the country followed the lead of Washington as many as 300,000 of our neighbors—grandparents and farmworkers and health professionals—might still be alive.[i] Scott AndersonGenesis 1:1-5 † Psalm 29 † Acts 19:1-7 † Mark 1:4-11 A video version of this sermon can be found here.

Scott Anderson2 Samuel 7:1-11, 16 † Luke 1:46b-55 † Romans 16:25-27 † Luke 1:26-38

A video version of this sermon can be found here. Would it surprise you to know that this story from Second Samuel, this story of the victorious King David, now settled in his reign, now looking to build a permanent temple for God did not actually come together at a time when “the king was settled in his house and the LORD had given him rest from all his enemies around him”? Would it surprise you to know that it came about much later, during captivity in Babylon, when the temple that David’s son Solomon ultimately built for the LORD lay in ruins along with much of the civilization Israel had known at its peak, when the best and the brightest and the most privileged of Israel’s citizens had been forced to resettle as refugees in a foreign land? Would it surprise you to know that it came about when there was no rest, no house, and no king?[i] Perhaps it doesn’t surprise you. Perhaps it surprises you no more than knowing the story of Mary and the angel Gabriel was written down a full generation or two later, at a time when this one whose birth is foretold, this Jesus the Messiah had been executed as an enemy of the state and the church, and this miraculous child John, of the eighty-something year-old Elizabeth, had been beheaded, and when the very structure of Jewish life that serves as the backdrop to this story had been undercut, when there was once again no rest, no house, and no king. What is it about this hope of ours, that it seems to thrive when things are unfinished, that it seems to flourish most in trouble, in suffering, and in need? What is it about this mysterious faith of ours, that it is strongest, according to Romans, when revealed after long ages of being kept secret? What is it about this love of ours, that it is made perfect in weakness? Scott AndersonIsaiah 64:1-9 † Psalm 80:1-7, 17-19 † 1 Corinthians 1:3-9 † Mark 13:24-37

A video version of this sermon can be found here. There is no less light in the world. I understand this may be difficult for us to imagine on these days in our Pacific Northwest when light seems to be such a scarce commodity. The comments began soon after we said goodbye to Daylight Saving Time and gave ourselves that extra hour of sleep—a brief reward for the inundation of darkness that now affords us only 8 hours and change of this dripping, gray miasma we now call daylight. If you’re among the small group who still commute farther than from your bedroom to your, I don’t know, bedroom, you probably go to work and come home in this blanket of darkness. It can be overwhelming. Especially so this year. But, unless you believe in a flat earth, and the heavens as some kind of a literal canopy above it, we know this is simply a matter of perspective. There is no less light in the world. We are simply spending more time in the shadows these days as our earth has begun that part of its travels around the sun that radiates more energy and light on the southern hemisphere than the northern. It’s a matter of perspective. The sun shines just as bright. The light is there, along with the dark. It always is. It’s just that we don’t get the same angle on it that we do in those July days when the light lasts for 16 hours and the darkness is almost non-existent to those of us who go to bed by 10 or wake up after 5. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed