Maggie Breen1 Samuel 15:34-16:13 † Psalm 20 † 2 Corinthians 5:6-10, 14-17 † Mark 4:26-34 You can view a video recording of this sermon here.

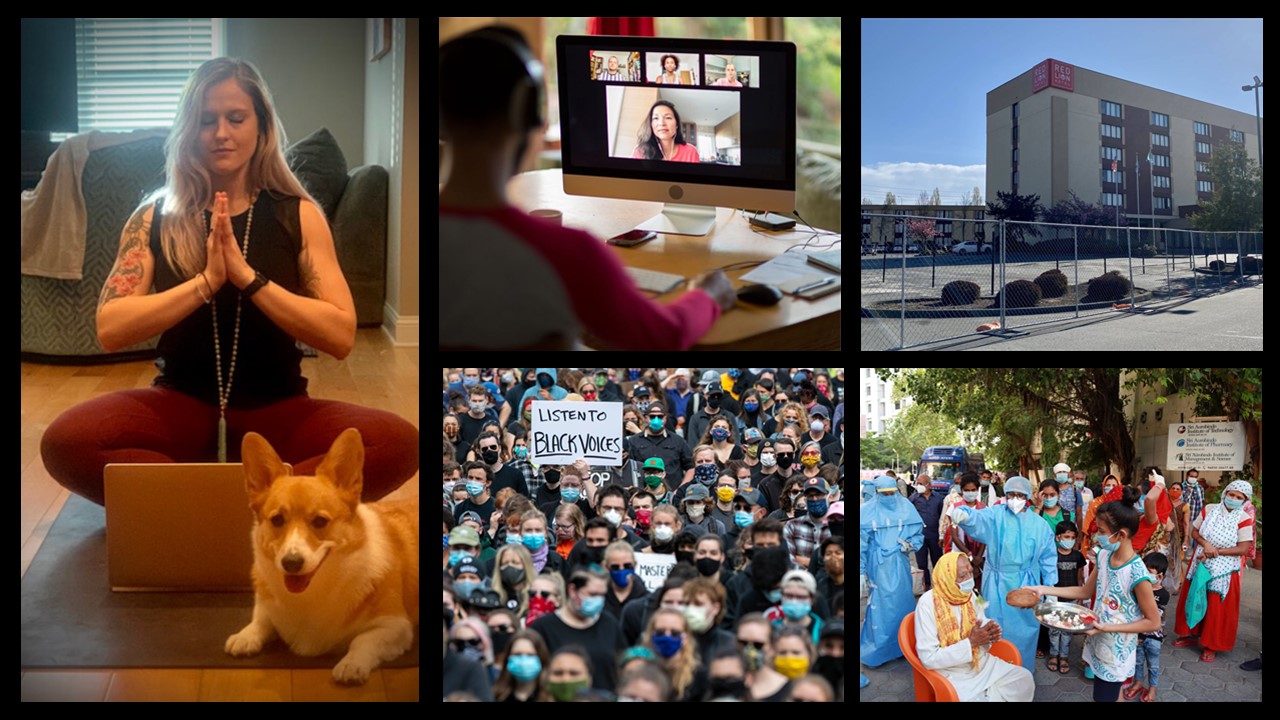

Isn’t that the case with so much of what we experience? We take something in, and we react, sometimes quietly, sometimes less so, but so often out of these hard-earned unspoken assumptions that have this silent power to affect our lives and the lives of others. Rosebay Willowherb, for me, used to be a sign of something bad and only something bad. It grew in my family’s yard starting in the late spring and early summer each year. Those stubborn stems with their long, thin, rough, dark green leaves that seemed to me to spiral like a screwdriver or a drill making its way through the low growth. And then as summer moved on those loud pink flowers, one atop the other, clamoring for the sky. And bees, lots of bees, would hang out in that slanting swath of pink and then the flowers would turn to these long thin seed capsules that would split open seemingly overnight to reveal this tangled mess of tiny, almost invisible brown seeds hidden in a mass of silk hairs that would carry them off in clouds. I lived until I was 15 years old in a long row of brick apartment buildings. Six houses per block, each block with a stone stairwell. At the bottom of each stairwell was a front door to the street and a back door that spilled out onto what felt like a lot of land – land that held so much of the lives of the people in that row of apartments. This land held two drying greens for every six houses and a small plot of yard for each family. There were no fences or hedges between the plots, except, I do remember, for an old rusty iron remnant of one in Mrs. McGee’s garden that we used for balance practice. Fireweed grew all over my yard. It also grew in some abandoned areas near our house, and around an informal dumping ground that was across and up the road a bit, and also it grew in a large piece of empty land right across from our building that didn’t seem to belong to anyone. The fireweed that grew wild in our neglected yard was to me a sign, a tall bright sign that things were not right. My parents were struggling, you see. A struggle that kept tending the yard miles from their chronically overcrowded radar. A struggle that had me on alert at all times, scared that others would find out what a mess things were, scared that at any moment things would fall apart in ways we could not possibly recover from. And that fireweed, that pink weed all over our yard that no-one went into not even during the most serious games of hide and seek, that fireweed screamed to the neighbors, screamed to my friends, that my family was not functioning as it should. It gave me away, in my mind. It made visible everything that I was trying so hard to hide. It was giving me away right there in my playground. Man, I hated that flower and long after I left my parent’s house, every time I saw it, it would send a shudder of shame and sadness and anger through my body that I knew, but that I couldn’t yet put words around. Many years later I was with some classmates reading some books trying to understand something of this new home of mine in the Pacific Northwest. The various authors we were exploring talked lovingly about the contours of this place: about indigenous folks - their rich and varied lives and their stories of persistently seeking and celebrating the promise and the love of life even after the monstrous loss that came and still comes with white settlers. About mountaineers and their knowledge, their need for and their awe of this land, and about loggers – those often vilified for the ways they have taken unsustainably from this land for the sake of earning a living, for other people’s profit, but who also in so many cases were so clearly, deeply in love with the land and looking for life also amidst their own stories of loss. One of the authors, Timothy Egan, in his book The Good Rain talked about this resilience and rebirth and held up the example as a bit of a metaphor of a number of plants that make a way after natural disaster around these parts. “Fireweed and Lupine,” He said [are] the vanguard of a forest that will take hundreds of years to return to climax phase, [and they] seem to need nothing more than air and water to proliferate” A plant that grew in empty places. I felt the tug of something I was familiar with, some part of my story, and also, at the same time this strange invitation to see something new. I stopped reading immediately to google this Fireweed he mentioned and there it was. There was that plant I hated, the sign of so much that was wrong but also somehow in his telling a vanguard, a herald, an early sign, and as it turns out the power behind something good, something beautiful. I was ready to learn more in that moment. So, I spent some time with firewood and what it meant over the next days and weeks. I explored with curiosity and this strange sense of peace and delight even the feelings and questions that were raising to the surface for me and I talked with some others who knew some things about this plant. I learned that Fireweed is a colonizer. Not like humans tend to colonize. When humans colonize, they tend to do so as a way of extracting from and exploiting the land and the people indigenous to that land. That is not what Fireweed does. Nope. Fireweed is a colonizer that brings life to spaces that seem dead. In Britain it was found all over bombsites during the war. It grows here, as you can tell from its common name, after fires. Firewood’s tiny and incredibly hardy seeds are designed to take root in the ash of destruction, and they work in those places to return nutrients to the soil. It grows rapidly, spreading underground through a powerful root system and it makes a home for bees and other pollinators, for the insects and the mammals that want to belong again. Fireweed was one of the first plants to emerge after the 1980 eruption of Mount St Helens. Over 200 square miles of forested terrain was blanketed in ash and over 100,000 young trees and saplings perished in that sudden event, yet within one month fireweed seeds had found the ashen soil and its rough green shoots were starting to drive their way to the light. It is estimated, that just a year later, Fireweed represented about 80 percent of all new seedlings around the volcano. Today thanks in large part to the early work of Fireweed and plants like it, the place is coming back to life. Colonizer plants reestablish what the ecosystem needs to be healthy again. They are nature’s response – and I think they are a good representation of the Spirit of God’s response - to trauma. Fireweed comes in these tiny seeds, seeds that can fly miles and miles, finding their way into the most unforgotten spots, and raising up colonies of plants that can grow up to 9 feet tall and can produce up to 80,000 seeds per plant. Seeds marvelously equipped and ready to fly again looking persistently for the places that need them. I had been offered a new story about something familiar to me. A story that held what I knew and at the same time pushed me just a little off kilter in its suggestion than there was more to things than the story I was stuck in. My body and my mind knew that the time was right to pursue the questions that had been planted and nurtured in me by my experience, and with the help of some wise guides, I found a bigger more life-giving reality. Now, today I know this plant as a beautiful sign of a God who never gives up on us. Who makes a way when there is no way. With what can we compare the kingdom of God, or what parable will we use for it? This is what Jesus asks those who have come to listen and to learn from him. In answer to his own question, he compares the kingdom of God in these stories today to the work of little seeds. The kingdom of God is like a seed that has all this potential which we did not create, and which we do not control, and which when ripe will produce for us a harvest. And the kingdom of God is like a mustard seed. This tiny seed that grows to produce an abundant home for others. The writer of this gospel then tells us this: “With many such parables he spoke the word to them, as they were able to hear it; 34he did not speak to them except in parables, but he explained everything in private to his disciples.” How true this is! The gospels are full of parables and a lot of them start with those words… the Kingdom of God is like…. These parables describe God’s presence amongst us in a myriad of different ways using a host of different images and characters. And they pack a punch thanks to both their ordinariness and to their strangeness. The ordinariness draws us in – their characters and subjects are familiar and we can relate. I don’t know about you, but I am still grabbed by the ordinariness of these stories from 2 millennia ago. They are stories told with love about ordinary lives, things the people of the time knew and cared about and things we know and care about still. Things like working, making a living, raising a family, cooking, eating and drinking, celebrating, and making a life with others. And as they tell their ordinary tales they concern themselves with things we all need and that we all seek – things like forgiveness, home, meaning, beauty, community, security, justice, peace. But then there is this strangeness, a turn in the story or a detail that would have made the listeners of 1st century Palestine double-take but a strangeness which might be harder for us from our vantage point to catch. The kingdom of God is like a mustard seed. A mustard seed? A mustard seed was a weed. It is firewood or dandelions or mint or blackberries. It will take over. No self-respecting farmer or serious gardener would let mustard seed take root in their carefully tended fields. This detail is intended I think to catch those who were listening and move them from images of God as triumphant, grand - like a powerful king or judge - and towards the claim that God can be one who shows up in persistent, difficult ways, in unexpected ways, in ways that we may be tempted to purge and throw away – and as one who shows up in these ways to bring abundant life not just to us, but for those diverse others that we so often don’t see or take account of. We must as followers of Jesus and as people of the book mine these old biblical stories carefully to get to some of these important insights, insights that we might otherwise miss, and we should also remember that stories of God, the stories of how God is at work in our lives do not start and finish with the stories in this book. The Spirit of God is at work all the time weaving its ordinary and strange tales in your life and in mine and in the stories of the world around us. Stories that will whisper to us from unexpected places. Stories that will nudge us and push us slightly off kilter with suggestions of new and wider truths in the things we thought we knew. Stories that will speak deeply to our experience and catch as we are ready, beckoning us to pay attention for new broader realizations that are growing in and amongst us. Stories that we must take to this book and to this way and to each other so that we as we discern together, figure out what they have to say about how God is showing up in our world today. Now honestly, if we were not in this strange post-pandemic time, I think I might be preaching on the need to be open to the places that God is trying push us off kilter, asking us to look beyond what we know, asking us to see a larger reality, but right now, beloved, we do not have to look very far or very hard for stories that will challenge what we thought we knew. We together, all of us, each of us, have been through something big these last 16 months. It has been ordinary, so very ordinary. Long, long, ordinary days at home, caring and hoping that those we know, and those we don’t, will stay well and have what they need. Long ordinary days just trying to keep it all together. And it has been beyond strange – wouldn’t you say? There are new perspectives and invitations to see in new ways all around us: in how our work might get done and how much work we really want to do; in how we might care for ourselves and the things that bring us life; in new slants on how we might build community and take care of each other; in rising, urgent, persistent demands around how health care, housing, income, you name it gets delivered and to whom; in new realizations about how best children might be educated and what they need to grow fully; and in new questions and thoughts about what it looks like to show up for others that are not treated with equity and just what we are or what we are not willing to risk to do so. I certainly think that in the midst of this unsettling, strange time, the charge to look for where God might be calling us to see something new and pursue it is as important as ever. And also beloved, if you are feeling overwhelmed and trying to recover; if you are feeling unsure about what questions are yours to pursue and how all that is being raised up intersects with your particular tender story, your particular experience and gifts; if you are scared, anxious, that it will all be too much for us and we will rush back to “normal” without leveraging this opportunity for something new, something better then I think the good news today might be that we can take the breath we need and trust that God will see to fruition the seeds that God has planted in us and around us. We can trust, we really can, that the questions that are ours to follow will not let us go, they will be there ripe for harvest when we are ready, and God who planted will tend to then, tend to us and will wait for us to harvest them. So maybe you are feeling strong and ready to give voice and to pursue new perspectives and new questions; maybe you are unsure and need some time to recover and work out what is next; or maybe you are feeling some combination of these or other things. Know beloved, trust that you are where you should be, and the Spirit of God is with you in all of it, all of it. The Spirit of God is with you like fireweed after change making a way, setting the conditions for new life. May we trust this, and may we be with each other tenderly in this new place nurturing and tending to what is real. May we, in God’s peace, find the courage and the safe space to name what is real for us and to offer the kind of space that helps do the same as they are ready and able. And as the time is right may we with curiosity and hope catch and follow what is rising up for us, and what needs to be pursued for the sake of widening the story so that we and all others may have the full life that God wants for all.

Amen

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed