Scott Anderson1 Samuel 1:4-20 † 1 Samuel 2:1-10 † Hebrews 10:11-14, 19-25 † Mark 13:1-8 You can view a video of the service and sermon here. Franz Dolp was a professor of economics at Oregon State University when he began, perhaps, the greatest work of his life. As a young father and professor, his marriage had eroded, and his dream of creating an Oregon homestead with it. When he drove away from the farm intended for “till death do us part,” it was with the good-bye blessing, “I hope that your next dream turns out better than your last.”[i] He eventually found his way to forty acres on Shotpouch Creek. This logged-out, chaotic hot mess of vine maples, leggy hardwoods, and thorns was in the same Oregon coast mountains where his grandfather had made a hardscrabble homestead. In his journal, Franz wrote that he had “made the mistake of visiting the farm after it was sold. The new owners had cut it all.” I sat among the stumps and the swirling red dust, and I cried. When I moved to Shotpouch after leaving the farm, I realized that making a new home required more than building a cabin or planting an apple tree. It required some healing for me and for the land.”[ii] “My work [at Shotpouch] grew out of a deeply experienced sense of loss,” he wrote, “the loss of what should be here.”[iii] Robin Wall Kimmerer tells the story of how Franz Dolp, a wounded man, moved to live on wounded land at Shotpouch Creek in her book Braiding Sweetgrass, in a chapter she titles “Old Growth Children.” Franz wrote in his journal, “These forty acres were to be my retreat, my escape to the wild. But this was no pristine wilderness.” The land was razed by a series of clear-cuts over the years—first the venerable old-growth forest and then its children. No sooner had the Doug firs grown back than the loggers came for them again.[iv] Everything is different after land is clear-cut. Sunshine is abundant, the soil is broken open and unstable, temperatures rise, the humus blanket gives way to exposed minerals. Forest ecosystems have tools for dealing with disturbances, of course. Early plants get to work on damage control, quickly.

0 Comments

Scott AndersonRuth 3:1-5, 4:13-17 † Psalm 127 † Hebrews 9:24-28 † Mark 12:38-44

You can view a video of the service and sermon here. Robin Wall Kimmerer tells of an ancient ceremonial tradition among the indigenous coastal people in the Northwest. It always happened about this time of the year. If you’ve been out and about on the rivers in the past month or so, paying attention to what’s been happening in our waters, it may not surprise you. Kimmerer spotlights the story this way: Far out beyond the surf they felt it. Beyond the reach of any canoe, half a sea away, something stirred inside them, an ancient clock of bone and blood that said, “It’s time.” Silver-scaled body its own sort of compass needle spinning in the sea, the floating arrow turned toward home. From all directions they came, the sea a funnel of fish, narrowing their path as they gathered closer and closer, until their silver bodies lit up the water, redd-mates sent to sea, prodigal salmon coming home.[i] Scott AndersonIsaiah 25:6-9 † Psalm 24 † Revelation 21:1-6a † John 11:32-44 You can view a video of the service and sermon here. It took me about two minutes the other day to remember the name for these. I could see them in my mind’s eye, and I knew they were in the fridge right next to me, but I was determined to flex those memory muscles and work past this mind block. Every time the words came close to my consciousness, stupid broccoli kept getting in the way. Bru, bru, bru…broccoli.

No! Finally, I got it! I conquered! “Brussel sprouts!” I shouted to Barb who I suspect, by that point, was looking a bit anxious. It was almost as if I had to look out of the periphery of my brain to do it, but I prevailed! Scott Anderson1 Samuel 17:57-18:5, 10-16 † Psalm 133 † 2 Corinthians 6:1-13 † Mark 4:35-41 You can view a video recording of this sermon here. I had never before noticed the cushion. Did you catch it? Jesus was in the back of the boat, asleep on the cushion before they woke him up. That’s a peculiar detail that is included only in Mark. I mean, what are we talking about here? Was it some kind of flotation device or seat pad? Maybe it was something more practical for the skipper. I mean, how luxurious was this setup?

I did have to laugh though when I read this detail in my research: “… it is important to avoid a translation which would suggest that Jesus was so small or coiled up as to be able to sleep on a single pillow.”[i] Maggie Breen1 Samuel 15:34-16:13 † Psalm 20 † 2 Corinthians 5:6-10, 14-17 † Mark 4:26-34 You can view a video recording of this sermon here.

Isn’t that the case with so much of what we experience? We take something in, and we react, sometimes quietly, sometimes less so, but so often out of these hard-earned unspoken assumptions that have this silent power to affect our lives and the lives of others.

Rosebay Willowherb, for me, used to be a sign of something bad and only something bad. It grew in my family’s yard starting in the late spring and early summer each year. Those stubborn stems with their long, thin, rough, dark green leaves that seemed to me to spiral like a screwdriver or a drill making its way through the low growth. And then as summer moved on those loud pink flowers, one atop the other, clamoring for the sky. And bees, lots of bees, would hang out in that slanting swath of pink and then the flowers would turn to these long thin seed capsules that would split open seemingly overnight to reveal this tangled mess of tiny, almost invisible brown seeds hidden in a mass of silk hairs that would carry them off in clouds. Scott Anderson Isaiah 6:1-8 † Psalm 29 † Romans 8:12-17 † John 3:1-17 For perhaps ten thousand years on this continent, long before modern industrial monoculture farming methods became dominant, women mounded up the earth and planted three seeds right next to each other in the ground. Robin Wall Kimmerer tells us of this story of the Three Sisters in her book Braiding Sweetgrass.

Together these plants—corn, beans, and squash—feed the people, feed the land, and feed our imaginations, telling us how we might live. For millennia, from Mexico to Montana, women have mounded up the earth and laid these three seeds in the ground, all in the same square foot of soil.[1] Do you recognize the strands of knowledge and understanding, and mystery Kimmerer is braiding together here as she talks about these plants—corn, beans and squash? The plants feed the people, feed the land. And they feed imaginations. They teach lessons about morality and purpose, about what it takes to live fully, to live well, and to live long—if we have ears to hear (no pun intended). Scott AndersonActs 2:1-21 † Psalm 104:24-35b † Romans 8:22-27 † John 15:26-27, 16:4b-15

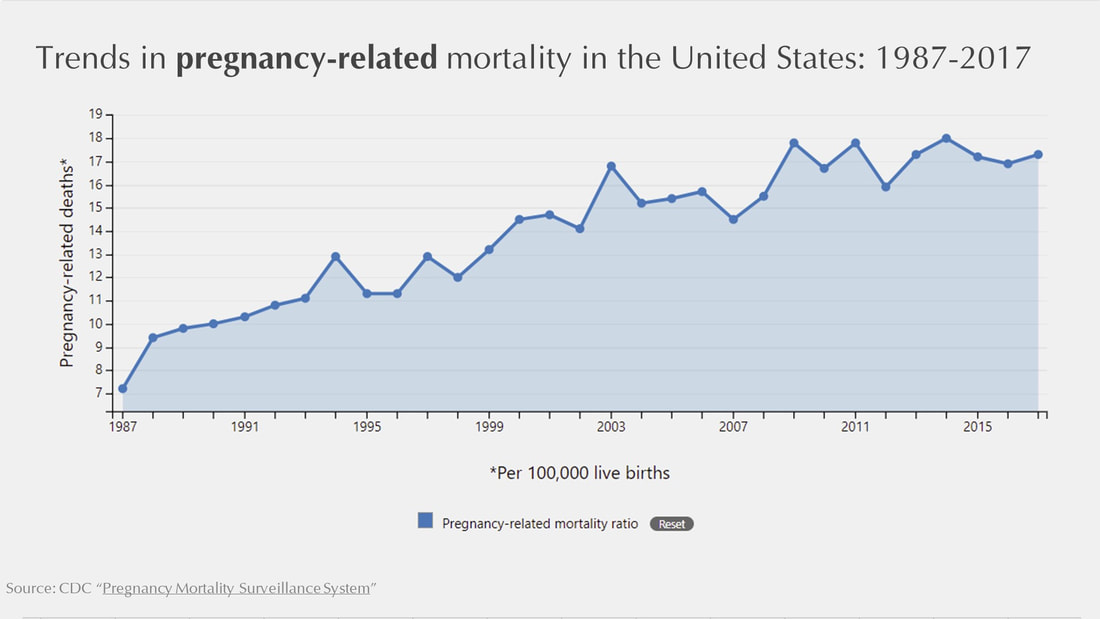

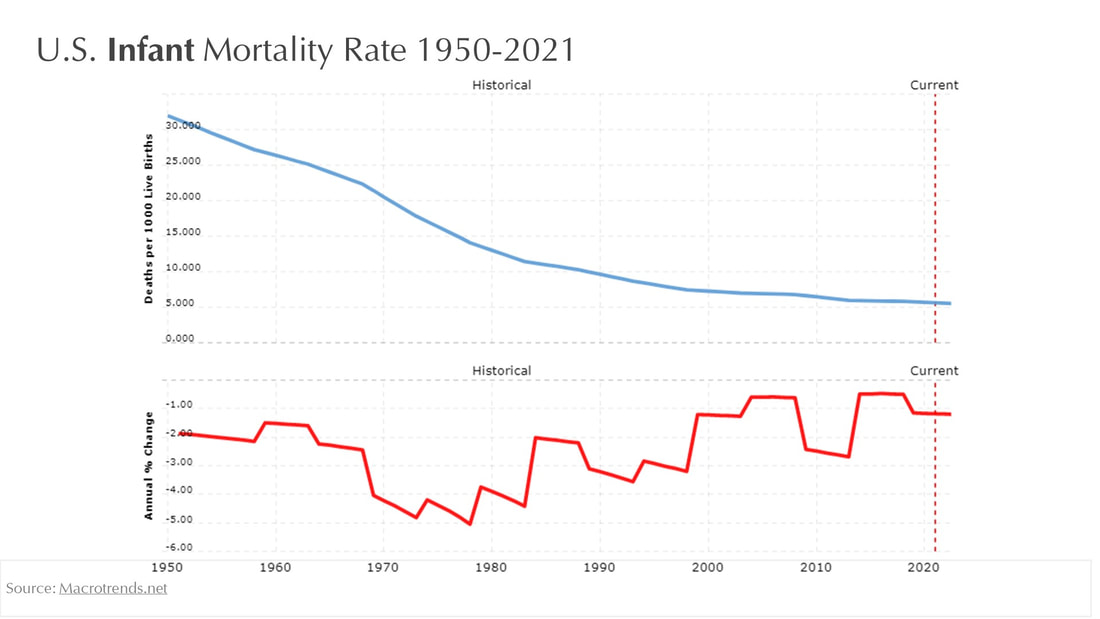

This was not the first time that fire from heaven came down on the earth. It had happened before. In Exodus[i] we read that fire from heaven descended on the Tent of Meeting. It says, “Moses was not able to enter the tent of meeting because the cloud settled upon it, and the glory of the Lord filled the tabernacle.” Amid the 40 years of wilderness wanderings, whenever it lifted the Israelites would move, but when the cloud of fire settled on it, the Lord was in the tabernacle, and they stayed where they were. The theologian N.T. Wright[ii] reminds us it happened again in 1 Kings[iii]. For generations God lived in the Tent of Meeting, even after David the king had a home of his own. Finally, around 950bce, Solomon, David’s son, had finished the temple. God finally had a permanent home, and on the day of dedication, fire filled the temple in much the same way it had filled the tent of meeting. “The Lord has said that he would dwell in thick darkness,” Solomon proclaims. “I have built you an exalted house, a place for you to dwell forever.” And so God’s presence was assured for the Jewish people, and, in the thinking of this small tribal affiliation known as Israel, Solomon’s Temple became the centering place of the whole world. Scott AndersonActs 1:15-17, 21-26 † Psalm 1 † 1 John 5:9-13 † John 17:6-9 A video version of this sermon can be found here. Perhaps you are aware that the US is the only developed country in which pregnancy-related mortality—deaths of women in childbirth—is actually going up rather than down. And while rates of infant mortality have generally gone down over the years, infant mortality remains a big problem among some populations—this in a country that has demonstrated such astonishing scientific capabilities when it comes to things like rapidly developing vaccines in a crisis that we are able to anticipate being back together next week. As of 2020, American women were far more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than women in other wealthy countries.[i] There is an important, and startling caveat to all this, though. These numbers are not trending across the board. Both of these rates are driven by what is going on with Black women and babies.

Scott Anderson Acts 10:44-48 † Psalm 98 † 1 John 5:1-6 † John 15:9-17 A video version of this sermon can be found here. You likely read the quote from the Robin Wall Kimmerer we included in the invitation to worship. Here it is again, from her book Braiding Sweetgrass: “It’s funny,” she writes, “how the nature of an object—let’s say a strawberry or a pair of socks—is so changed by the way it has come into your hands, as a gift or as a commodity. The pair of wool socks that I buy at the store, red and gray striped, are warm and cozy. I might feel grateful for the sheep that made the wool and the worker who ran the knitting machine. I hope so. But I have no inherent obligation to those socks as a commodity, as private property. There is no bond beyond the politely exchanged “thank yous” with the clerk. I have paid for them and our reciprocity ended the minute I handed her the money. The exchange ends once parity has been established, an equal exchange. They become my property. I don’t write a thank-you note to JCPenney.[i]

Scott AndersonActs 8:26-40 † Psalm 22:25-31 † 1 John 4:7-21 † John 15:1-8

A video version of this sermon can be found www.standrewpc.org/sermons/5th-sunday-of-easter-year-bhere. It is important to notice, when we look at this Acts story of Philip and the Ethiopian Eunuch that it is a story with three characters not just two. Great detail is provided about the first two—unusually detailed information, in fact. This isn’t like some of Luke’s other stories where people are left in mystery. We know a great deal about Philip from other texts in Acts—he is a deacon: one of seven Greek-speaking Jewish Christians appointed by the Twelve to tend to the needs of others, especially widows in the Greek-speaking portion of the fledgling Christian community. He is known as Philip the evangelist. He eventually settled in Caesarea, a government seat in first-century Palestine. He had four daughters who were considered prophets.[i] We know perhaps more than we want to know about the Ethiopian. They are in charge of the treasury of the Candace, which is the official title of the queen mother who is head of the Ethiopian government. We know by their chariot that they have status. We know by their scroll that they can afford rare things. We know by their Greek that they are educated. We know by their reading Isaiah that they are devout. We know by their invitation that this Ethiopian is humble enough to know what they don’t understand and to ask for help, and hospitable enough to respond to Philip when he approaches. And we know, because the author of the two volume Luke-Acts story tells us five times, that they are a eunuch. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed