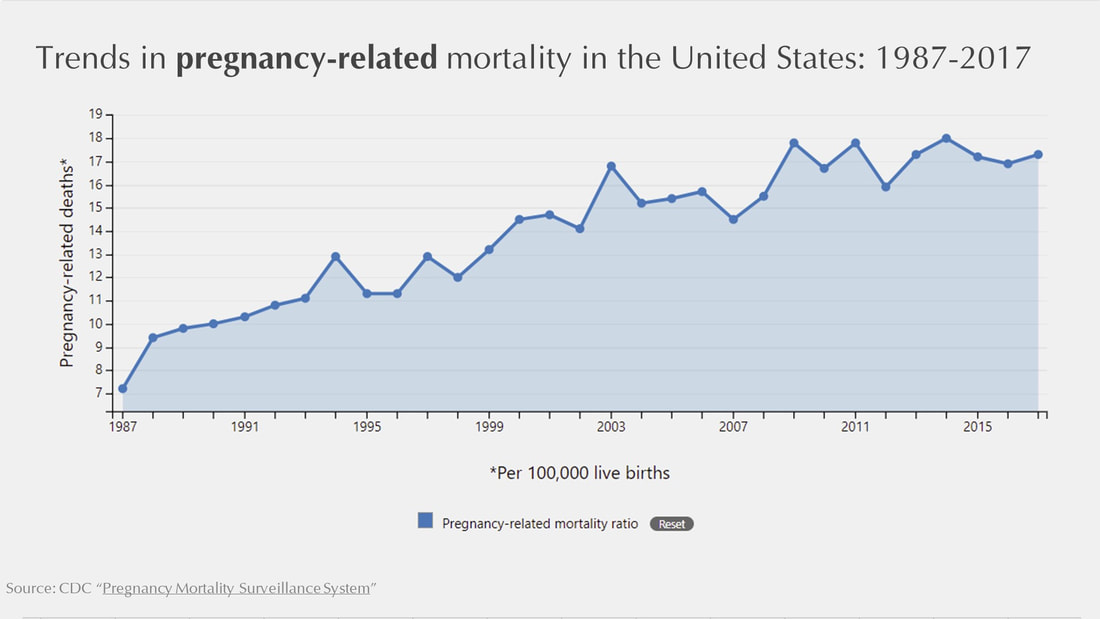

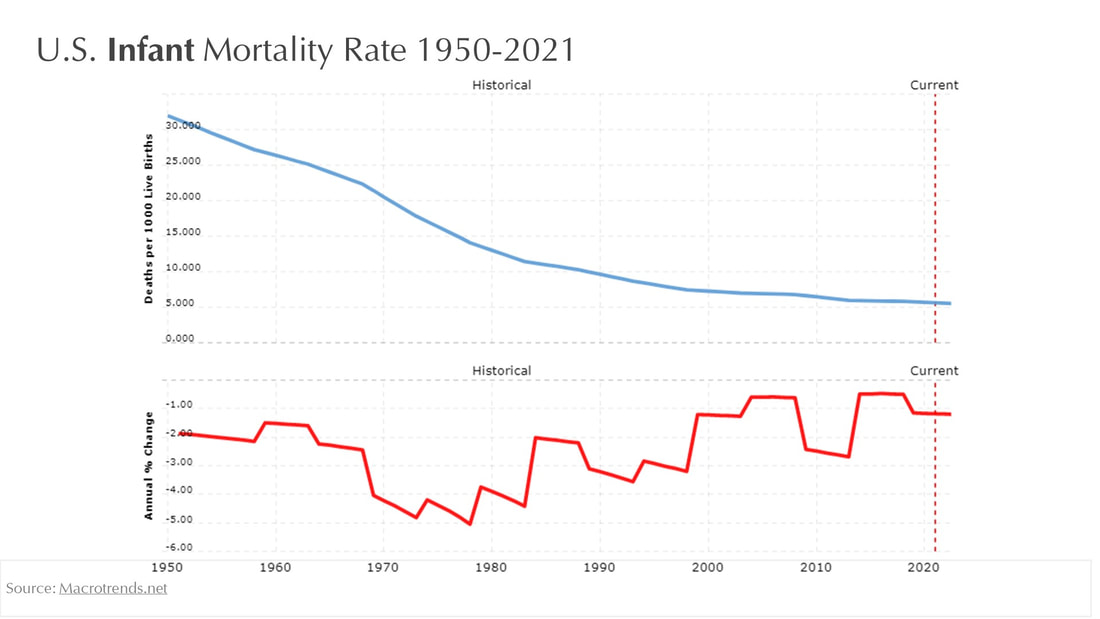

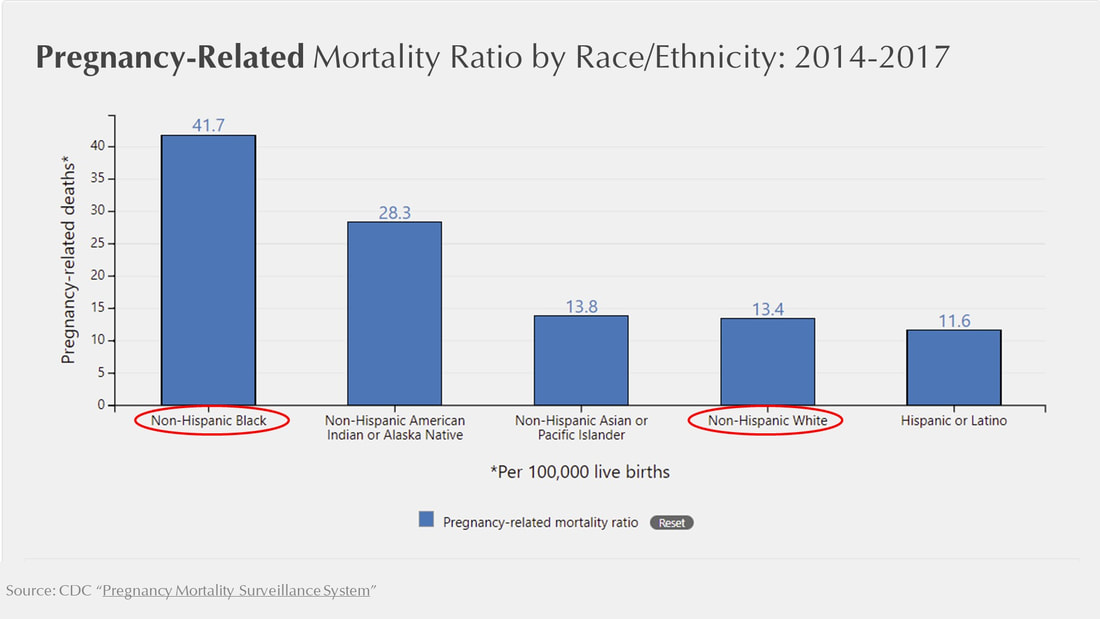

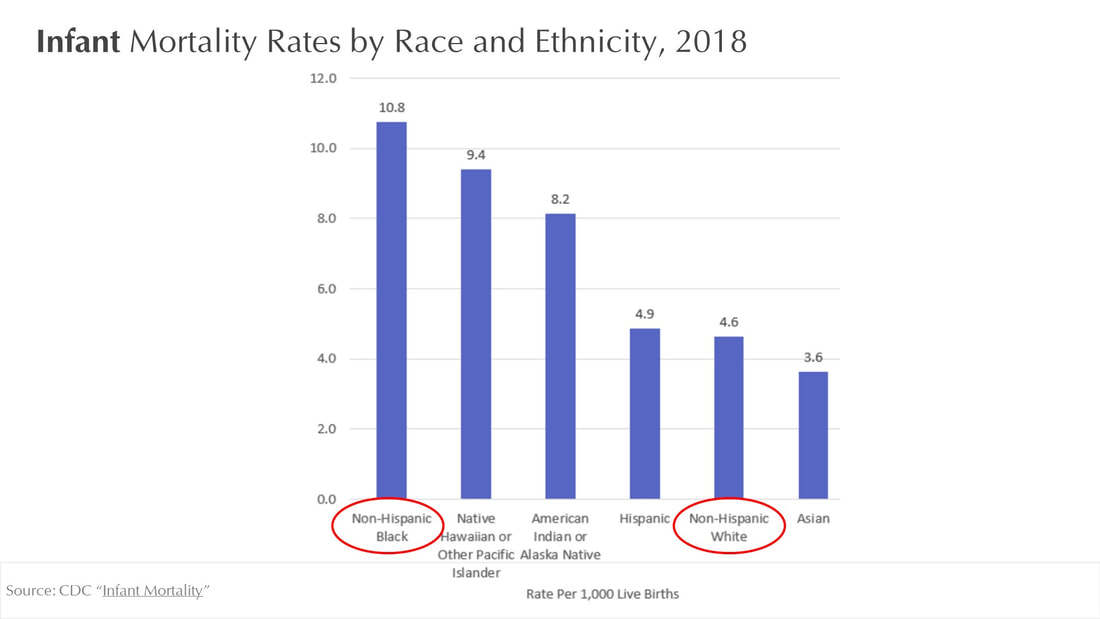

Scott AndersonActs 1:15-17, 21-26 † Psalm 1 † 1 John 5:9-13 † John 17:6-9 A video version of this sermon can be found here. Perhaps you are aware that the US is the only developed country in which pregnancy-related mortality—deaths of women in childbirth—is actually going up rather than down. And while rates of infant mortality have generally gone down over the years, infant mortality remains a big problem among some populations—this in a country that has demonstrated such astonishing scientific capabilities when it comes to things like rapidly developing vaccines in a crisis that we are able to anticipate being back together next week. As of 2020, American women were far more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than women in other wealthy countries.[i] There is an important, and startling caveat to all this, though. These numbers are not trending across the board. Both of these rates are driven by what is going on with Black women and babies. Black women are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes as white women, and Black infants are more than twice as likely to die as white babies—this disparity is actually wider than it was in 1850, 15 years before the end of slavery.[ii] Let that sink in, for a moment. In comparison to other groups, the divide in the experience of quality of care in childbirth is wider now that it was when Black women and their children were enslaved and counted as property. And the problem is so significant among Black women and babies that it drives up the entire US rate for both statistics.[iii] The problem, plain and simple, is racism. When it comes, for example, to infant and maternal mortality, research has clarified what is behind these startlingly incongruent rates. It is not because Black women do not take care of themselves. It is not because they get inadequate pre-natal care either—although they often do. It is not because they are somehow more irresponsible than any other mother. When pre-natal care is equal, Black women still have small and pre-term babies. It also does not have to do with education. In fact, a Black woman with an advanced degree is more likely to lose her baby or die in delivery than a white woman with less than an eighth-grade education.[iv] And it also doesn’t have anything to do with genetic differences. Simply put, something about growing up as a Black woman in America is bad for your baby’s birth weight and threatening to her survival. It isn’t poverty. It isn’t irresponsibility. It isn’t inherited. It is the lived experience of being Black in America. It is the result of systemic racism. A sea of research over the last few decades has clearly indicated that these disparities are directly attributable to bias and to toxic psychological stress experienced as a result of systemic racism. An article in the New York Times Magazine spells it out for us: For Black women in America, an inescapable atmosphere of societal and systemic racism can create a kind of toxic physiological stress, resulting in conditions — including hypertension and pre-eclampsia — that lead directly to higher rates of infant and maternal death. And that societal racism is further expressed in a pervasive, longstanding racial bias in health care — including the dismissal of legitimate concerns and symptoms — that can help explain poor birth outcomes even in the case of Black women with the most advantages.[v] In other words, it is solvable, even as it goes to the very heart of who we are, the morality of our culture, the story of us we have told ourselves for so long, and our willingness to give ourselves to a new story of reciprocity, to a larger sense that we belong together, that we are responsible for one another. It is, for we who consider ourselves followers of Jesus, a matter of living out our faith. Jesus’ prayer in John is confusing, and it creates challenges because of language that seems to limit the God who so loved the world, really the cosmos so much that, as Eugene Peterson’s translation The Message translates it, God moved into the neighborhood. But that’s what these texts for today are talking about. When Jesus says he and his followers are not of the world, but in it, I suspect it is fair to say that we understand ourselves to be committed to a different set of values, a different code that what is generally held in our broader culture—an anti-racist stance that is built on this idea that we belong to each other, that we are our brothers and sisters keepers, that our well-being is tied up in the well-being of others, and that as long as Black women and their children are at risk, or poor people are at risk, or our siblings with disabilities are at risk, then we all are at risk. We will see this more next week in the story of Pentecost. In that story something new happens. In biblical imagery before this, the glory of God had fallen in the form of fire from heaven onto the temple. At Pentecost it now descends on people. All people! Not just Jews, but Gentiles, people from throughout the world. Insiders and outsiders, poor and rich, slave and free alike. This, beloved siblings, is the beginning of our story. I suspect it is so important for us to remember that this story did not begin with us. We are the adopted children. This story begins in the fertile crescent we now know as the Middle East. And it began in Northern Africa. It began with Black and brown people, like Jesus. We are the ones who have been adopted into it. We are the ones who benefit from the witness of those first believers. We are the latecomers, the recipients of the generosity of the Spirit of Life. Jesus prays to his Abba an aspiration we seem to be so far removed from at this point in history: “Holy Father, protect them in your name that you have given me so that they may be one, as we are one.”[vi] We are not of the world, Jesus suggests; we are not to mirror its brokenness and toxic zero-sum competition. But we belong to the world and its well-being. We are to be different. We practice a different code, a different set of commitments that refuses to imagine we are not dedicated to its well-being. I’ve shared with you before a beautiful spoken word piece by a poet named Joseph Solomon. It is a Mother’s Day piece, but I think it illustrates this broader love beautifully, even as it takes seriously the unique dangers that people of Black and brown skin face disproportionately. It speaks to the deep sense of belonging and responsibility that falls in direct line with the truth of Jesus’ life and the faith that did not begin with us, but into which we are gratefully adopted. It was inspired by his experience at an airport. Have a look. We know without a doubt, Christianity was born in adversity, and its truest forms thrive there. We who have so much, who worry about so little, we can learn from this. And we can join it. Be a part. Learn from the wisdom that exists outside of our experience. And as we anticipate being together once again, as we are joined together on the other side of this pandemic experience having seen things we cannot unsee, our eyes opened to realities we can no longer deny, we can make a change. We can be a part of the tipping of this American life and this cosmic life towards a well-being that only comes with justice rooted in this mystical bond—our belonging to each other. We are one as God is one, and we can learn to live into this truth. And in so-doing we can realize what makes for our own life, our own renewal, our own salvation as well.

Thanks be to God. Notes: [i] Norton, Amy. “U.S. Leads Wealthy Nations in Pregnancy-Related Deaths.” WebMD, November 18, 2020. Retrieved on May 14, 2021 from: https://www.webmd.com/baby/news/20201118/us-leads-wealthy-nations-in-pregnancy-related-deaths#1. [ii] Linda Villarosa, “Why America’s Black Mothers and Babies Are in a Life-or-Death Crisis.” April 11, 2018 in The New York Times. Retrieved on May 11, 2018 from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/11/magazine/black-mothers-babies-death-maternal-mortality.html. [iii] See Michael Barbaro’s “The Daily” Podcast “A Life-or-Death Crisis for Black Mothers”. This statistic is cited at 10:30 in the podcast. Retrieved on May 11, 2018 from: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/11/podcasts/the-daily/mortality-black-mothers-babies.html?rref=collection%2Fbyline%2Fmichael-barbaro&action=click&contentCollection=undefined®ion=stream&module=stream_unit&version=latest&contentPlacement=1&pgtype=collection. [iv] See Michael Barbaro’s “The Daily” Podcast “A Life-or-Death Crisis for Black Mothers”. This statistic is cited at 11:00 in the podcast. Retrieved on May 11, 2018 from: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/11/podcasts/the-daily/mortality-black-mothers-babies.html?rref=collection%2Fbyline%2Fmichael-barbaro&action=click&contentCollection=undefined®ion=stream&module=stream_unit&version=latest&contentPlacement=1&pgtype=collection. [v] Linda Villarosa, “Why America’s Black Mothers and Babies Are in a Life-or-Death Crisis.” April 11, 2018 in The New York Times. Retrieved on May 11, 2018 from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/11/magazine/black-mothers-babies-death-maternal-mortality.html. [vi] John 17:1b.

1 Comment

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed