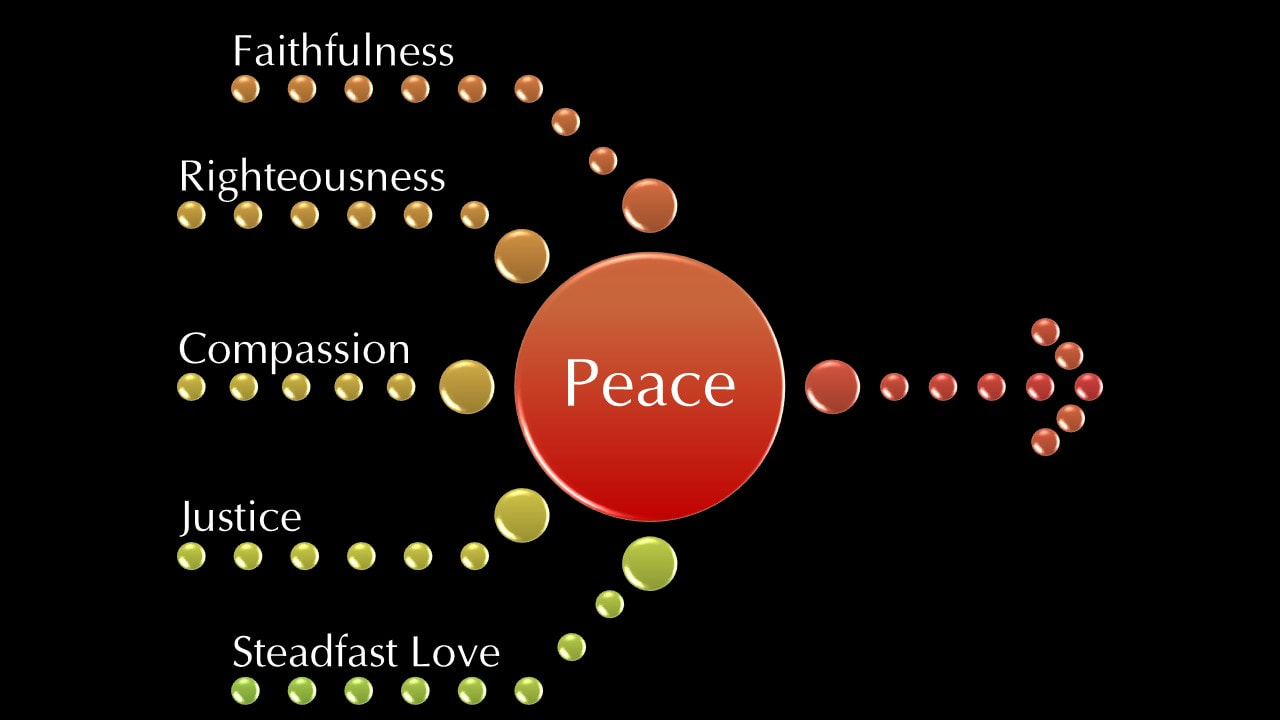

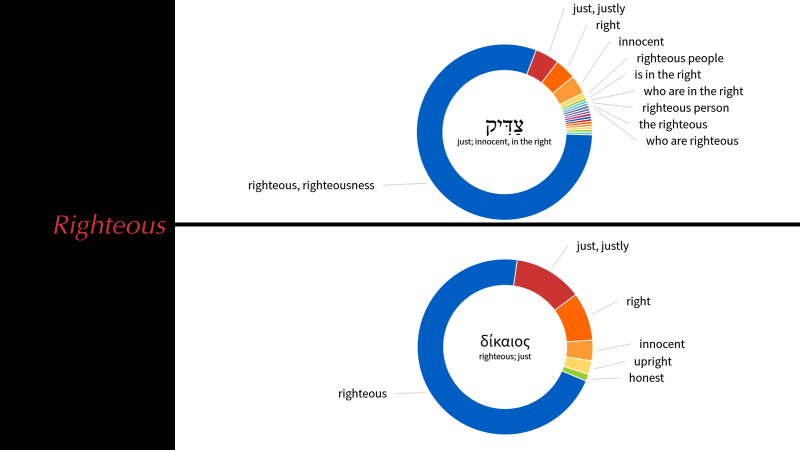

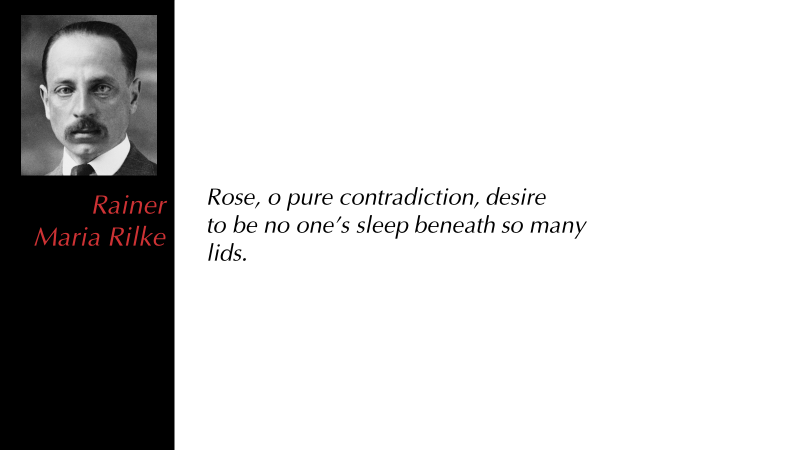

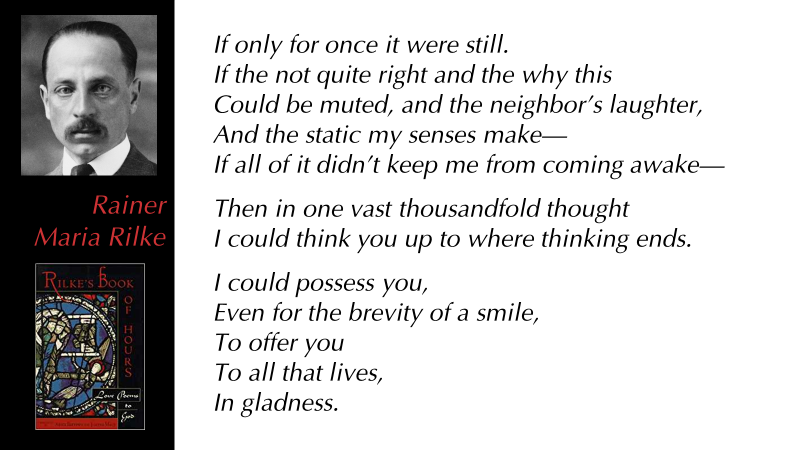

Scott AndersonJeremiah 2:4-13 † Psalm 81:1, 1—16 † Hebrews 13:1-8, 15-16 † Luke 14:1, 7-14 There’s a lot of things I love about doing this work I get to do with you. But one that always tends to bubble to the top for me is the privilege you sometimes give me to hold your stories—especially the most vulnerable and fragile ones. I wonder if you feel the same way about the life you share with one another? I wonder if you experience as well the mutual gift that it is to hold something fragile for someone else. I suspect those stories that feel most delicate for us feel that way because they scrape close to some of the deeper truths of our lives—those things we just can’t let go of, nor get past, the scars of our lives, the injuries that become something more. Their memories linger. They stay with us. Hold us and haunt us, and indelibly shape us. To share in those with you is, for me, to get close to bedrock, something deep and true and stable. Although it is also, and in the same breathless moment, to brush against something wild and feather-light. Maybe it’s something like this Hebrew notion of entertaining those angels unaware—our best nature and deepest truths—without knowing it, until the moment is past and all we have is the hindsight of resurrection and righteousness. I love, by the way, that these words we spent time with during Advent keep showing up. We shouldn’t be surprised, of course. They too are bedrock. You will remember these ideas, those words, those golden threads that wind their way through our scriptures and our traditions, that give us hand-holds when the way is slippery and uncertain, when meaning is manipulated, facts are denied, and truth is hard to hold onto, like it is in our current cultural moment: so faithfulness, righteousness, compassion, justice, and steadfast love lead us to the peace we crave. These words that wind their way through our scriptures, these complex ideas with their surplus of meaning stitch together our stories, sit us down at a table of love enfleshed, afford us waypoints to surely and steadily navigate our way when life is dropping bombs all around us. So, Jesus ends his story of a banquet with resurrection and righteousness. Sedeq in the Hebrew. Dikaion in the Greek. They carry all this nuance: Good deeds, righteous help, innocence, vindication, good judgment, right order, integrity. God’s will for salvation in action. Abraham believed God and it was reckoned to him as righteousness. Righteousness, which leads to peace. These are Sarajevo Roses. These are memorials of a sort in Sarajevo made by filling with a colored resin a scar in the concrete caused by an explosion. As you can see, there are quite a few of them—around 200—throughout Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina. They are the result of mortar rounds that fell on the city during the so-called siege of Sarajevo which lasted 1425 days—almost 4 years—in the early 1990s during the Bosnian War.[i] Someone noticed the scars left in the concrete looked like flowers, and so, from trauma came art that preserved and transformed a memory in a way that refused to forget and refused to give up. I wonder if this gospel story is trying to do something of the same thing—transforming a moment, making something new possible in the midst of a mess of a situation. The environment has become somewhat toxic, it seems, for Jeremiah and for Jesus. Moments intended to bring people together instead divide—the social pecking order, has become abundantly evident in the most common of events. For Jesus, a social gathering, a meal, has been reduced to one more mechanism to establish dominance, to identify insiders and outsiders. And the visual is evidence of a deeper need, of something going on in the human heart and in society, evidence of righteousness, or its absence. And so Jesus suggests a practice that just might change everything. Can physical relocation lead to the re-centering of our hearts? Can practice make us, if not perfect, perhaps more at peace? I’m talking about waking up—to what makes us truly alive. I’m speaking of expectations. Where you expect to be seated. What you expect to happen. Who you expect to engage in conversation and what you’ll talk about. Could it be that giving up our control, giving up our need to be somebody, opening up to what comes our way that we didn’t manufacture, might be just the key to our being the fullness of who we truly are? What needs do you bring to your tables and your social situations and your networks that may, in fact, limit you, undermine you, negate you? Settle yourself at a lower place. Humble yourself. Could that be just the thing we need for our renewal? “For all who exalt themselves will be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted.”[ii] Give up the need for privilege in whatever form it is most enticing: respect, honor, competence, expertise. And see what might happen. In other words, Jesus’ invitation to his table is an invitation to soul work. It is an invitation to remember who we already are, not what we think we need to become. Secure in the knowledge of God’s love for us we no longer have the need to promote ourselves. And through this righteous soul work, we begin to find our way to peace. No longer needing to be justified, we find ourselves ready to welcome the stranger to our table, and discover the stranger in each of us is welcome too. And we find ever-greater capacity to do the same more broadly—to joyfully welcome the poor, the lame, the crippled and the blind, the widow, the orphan, the immigrant—across our borders and into our hearts. Ready and able to share our food, and even our vulnerable, scarred and better selves. There’s a poet who, for me, is right for our time. He lived and wrote in Europe around the turn of the 19th century, in an age of disbelief, solitude, and profound anxiety. He died young, at 51 and chose a poem for his own epitaph that captures, I think, his captivation with the contradictions of life as he knew them, and Sarajevo, and us as well, no doubt. And they capture the desire to wholeness that I think lives deeply in each of us and around all our tables. But there’s another poem or prayer that Rilke left that I’ll leave us with. This from his astonishing Book of Hours, a collection of what I think could best be understood as a collection of prayers to God. Perhaps his fragile prayer is ours as well as we seek this narrow path of faith, scars and all. Amen.

Notes: [i] See, among others, the articles “Sarajevo Rose” and “Siege of Sarajevo” on Wikipedia. Retrieved on August 29, 2019 from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarajevo_Rose and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Sarajevo. [ii] Luke 14:11.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed