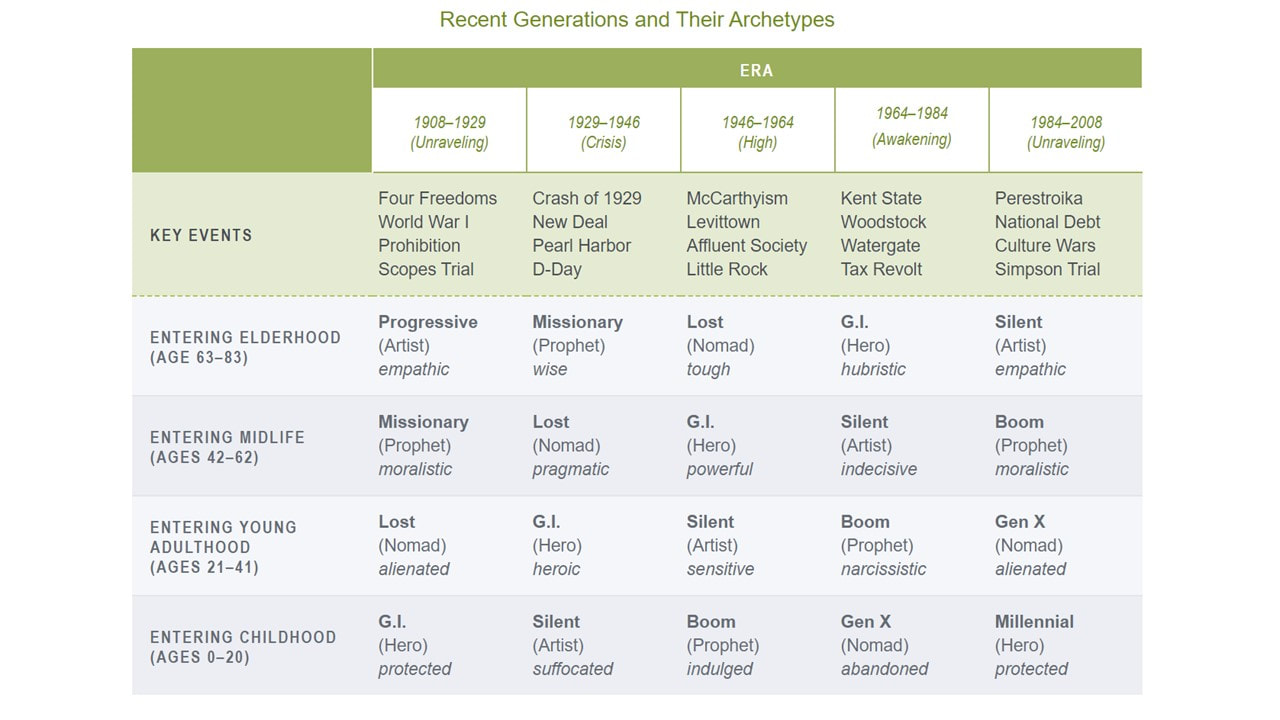

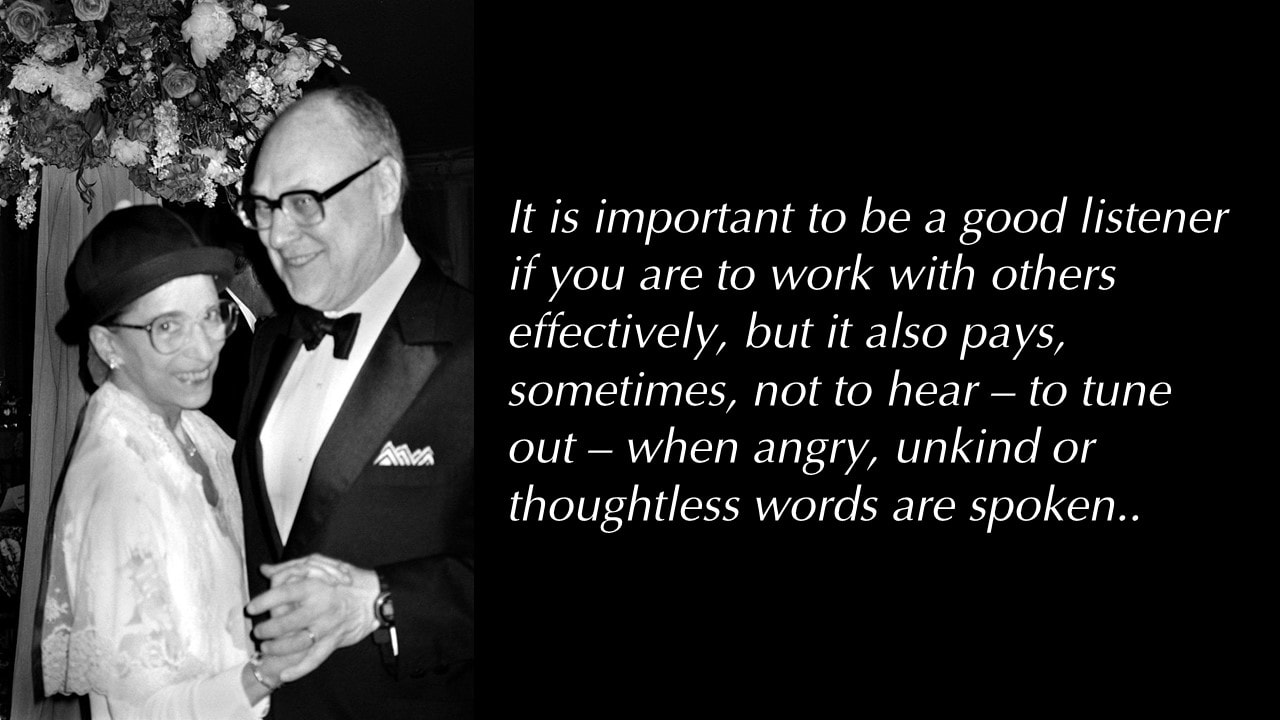

Scott AndersonDeuteronomy 34:1-12 † Psalm 90:1-6, 13-17 † 1 Thessalonians 2:1-8 † Matthew 22:34-46 Back in 2000 my daughter Claire and I went camping with a dear friend and his daughter. The next year another dear college friend and his daughters joined us. Soon enough, my son Peter was old enough and he started coming, building what became a summer camping tradition that lasted some 15 years—essentially through the school years of all our kids. The annual July drive to our camping trip in Mount Rainier National Park was always a highlight of the year. We hiked all through the park and in nearby locations. We celebrated meals together and spent long hours in conversation around the fire. We created memories that shaped us and will outlast my lifetime. The kids are older now. Half of them are married and have started their own families. There was one year, one conversation I was reminded of this week. We had been going to the same campground—Ohanapecosh in the Southeast corner of the Park—for at least a decade and we dads began to wonder if we ought to change it up a bit. So we proposed the idea of a new location, a new adventure for the following year to the kids. Before we could even finish the sentence, and with one voice they all cried out: “No! It’s tradition!” Now, let me try to explain the impact of this on me in the moment. This was about the same time that we were making some changes to the way we worship together here at St. Andrew. And I don’t mind saying, there was a bit of grief about it all. Some folks were understandably resistant to those changes and what they signaled, crying out a little like Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof, about the power of tradition to shape us, and resisting changes that seemed to threaten that identity. So to hear amidst a summer break from it all, the chorus line of my own children and their friends crying out on behalf of tradition caught me with, well, let’s just say a hint of irony. We have been talking for some years now about this era as one of major shifts. The old no longer works like it once did. Generations are pushing against other generations struggling to find ways into the future that work for everyone, even as it seems we are moving backwards more than we are forwards. The Sunday we mark the 503rd anniversary of the Protestant Reformation, so I suppose that also has me thinking about the nature of progress and transition in human life. Now, I’m a Gen Xer—an early representative to be sure, but that’s where I fall in the model theorized by William Strauss and Neil Howe as they lay out these generational archetypes in their books Generations and Turnings. One of the important aspects of my generation’s story is that we seem to be something of a middling bunch; we are nomads between settled homelands. Now, often that’s interpreted as a generalized judgment on the whole cohort—we’re just not that into being “into” things. You might call us a little cynical for our experiences having spent our early adult years alienated by something of an unraveling of society as we know it. But I also think it equips us for the role that we find ourselves in the moment, as we seek to find a way between perhaps more solid notions of what has been and what we hope will be, and as we as a cohort tend to be inclined to look for the way to new promises. That’s why I think Moses caught my attention this week, up there on the mountain looking down and being told he would not be going any further. We might read this story with some sorrow—that this leader who was “unequaled,”[i] who had given so much of himself to his people, must now end his journey before he can see for himself the fulfilment of all his efforts. It is a familiar story for my generation. I suspect it is even more familiar to the generations before mine—the artists and prophets among us who put all of their idealism and energy into creating a life for themselves and their children, who built up the institutions that are once again teetering and on the cusp of change, and—I believe—renewal and new possibility. It is no easy task to give up what you’ve known, and even more, to let go of those unfulfilled expectations. It is no easy task to give up the reigns of control when you feel like you know exactly what is required to engineer the promise you can just see on the horizon. But I suspect Moses’ story here speaks to the necessity of doing just that, ceding the future to those who will live in it. Blessing them with everything that you are. Indeed, this becomes one of the most important, and perhaps most difficult tasks of our lives. Cornel West, professor of philosophy at Union Seminary whose leadership has made tracks all over the landscape has said on many occasions that “justice is what love looks like in public. During a speech at Howard University in 2011[ii] he set the familiar quote in the context of a broader message which was, in a nutshell, “it’s not about you.” We might say it this way: it is never about me or you. It is always about us. Dr. West’s broader subject matter in 2011 was the hardship black and brown folks have experienced in America—the result of greed and selfishness, which are the roots of exploitation that produce the opposite of justice. But when it becomes about us and our well-being together, when we recognize the power we have to bless others and to bless other generations, when we recognize we have the ability to give our lives away, and to discover that to do so is to see it return to us, to see it reflected in a vastly better quality of life for all of us, to see it preserve a future of security and abundance and peace—whether that future represents the twilight of our lives, or simply a next chapter—then we have begun to realize the vision that Jesus imagined as he summed up all the law and the prophets in the commandments to love God and to love neighbor. Letting go is hard—especially if we want to do it in ways that empower the next generation, rather than further burden it. It involves a form of mentoring that does two things: We have to remain engaged. We must take all the power, all the control, all the wisdom and resources we have grown so accustomed to, and give it away to those who would take the reigns of leadership. It requires a generosity of spirit that keeps us lovingly engaged, while letting go of all those things you once thought were non-negotiable. Permission giving, and what Ruth Bader Ginsburg called being a “little hard of hearing” when the response to your sacrifice is not all you hoped it would be. Joe Ager, a pastor in Tacoma notes that in Matthew 22, Jesus’ opponents try to entrap Jesus in a war of words—first on politics, then on theology, then on the law. As they try with all their might to hold onto their power, their game is readily apparent: They are trying to trap Jesus in an impossible, exhausting, demoralizing purity test that he will later call a “heavy burden, hard to bear.”[iii]

How we know this feeling! The work of Christ, the work of now, is to remove those heavy burdens, to make way for others. The apostle shows us how in Thessalonians (2:7-8): “though we might have made demands as apostles of Christ:” But we were infants among you, like a nurse tenderly caring for her own children. So deeply do we care for you that we are determined to share with you not only the gospel of God but also our own selves, because you have become very dear to us. And for you who are younger, waiting in the wings, or perhaps deciding whether it’s worth the energy to take the lead, hear this: there is no time like the present. Now is your time to lend your leadership and your vision, to take on what needs to be done, even if it is not easily given or received. We do not know what will happen in these next few uncertain weeks, but it is very clear to me that, regardless of the election outcomes, we are on the brink of something new—a moment of the Spirit. So let us together take hold of the moment and live as children of the light—easing the burdens of a generation. And how do we know that God is with us? One of my favorite answers to this question is found in one of the great prayers of the church: We know because we will be led to places we did not plan to go. Thanks be to God! Eternal God, you call us to ventures of which we cannot see the ending, by paths as yet untrodden, through perils unknown. Give us faith to go out with courage, not knowing where we go, but only that your hand is leading us and your love supporting us; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen. Notes: [i] Deuteronomy 34:11. [ii] A summary of West’s presentation can be found at https://www.traffickinginstitute.org/incontext-cornel-west/ (Retrieved on October 23, 2020). The recording (linked in the text can also be found here: https://youtu.be/nGqP7S_WO6o (Also retrieved on October 23, 2020). [iii] Joey Ager. Word from Below: “The Impossible Purity Tests” Street Psalms listserv, October 23, 2020.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed