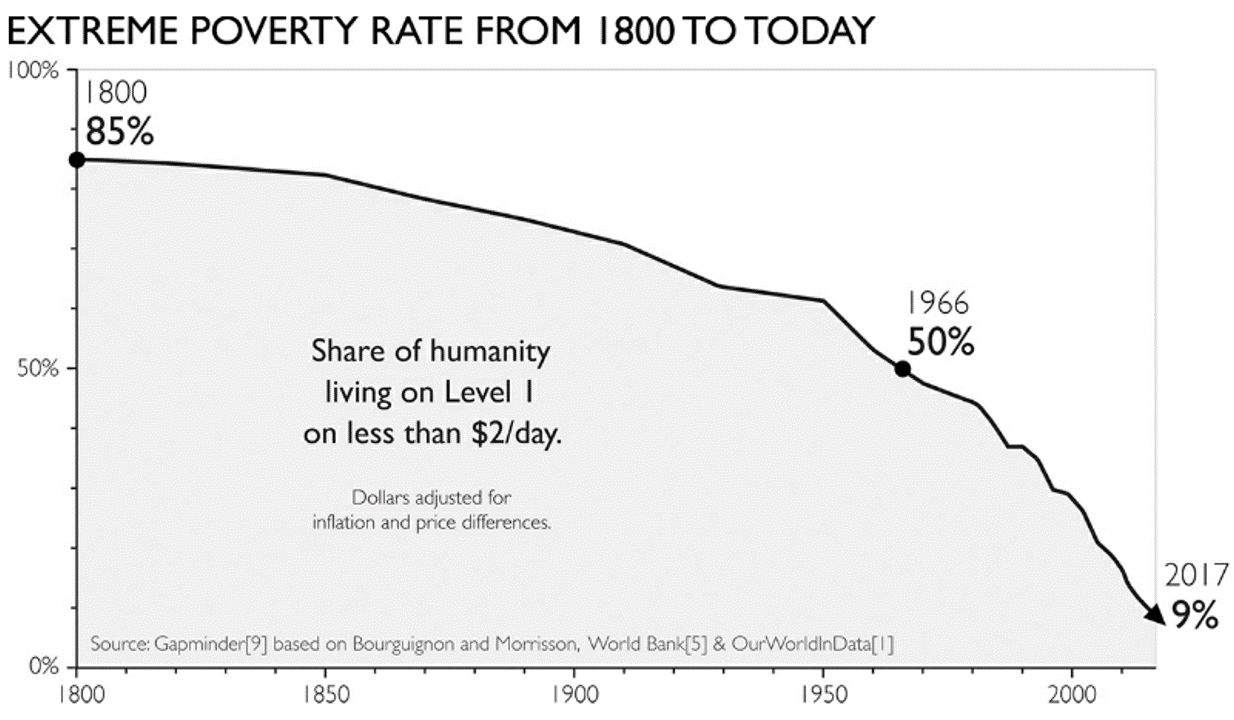

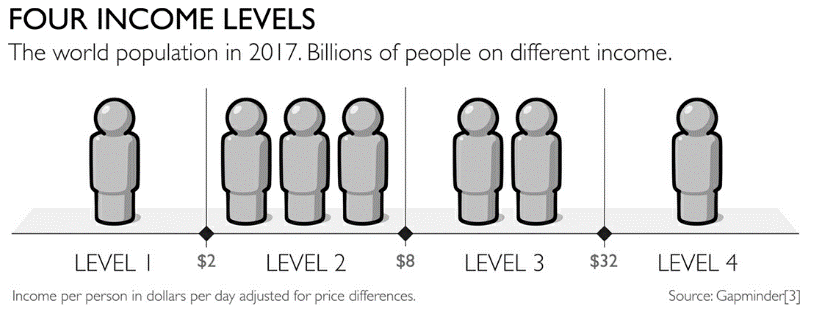

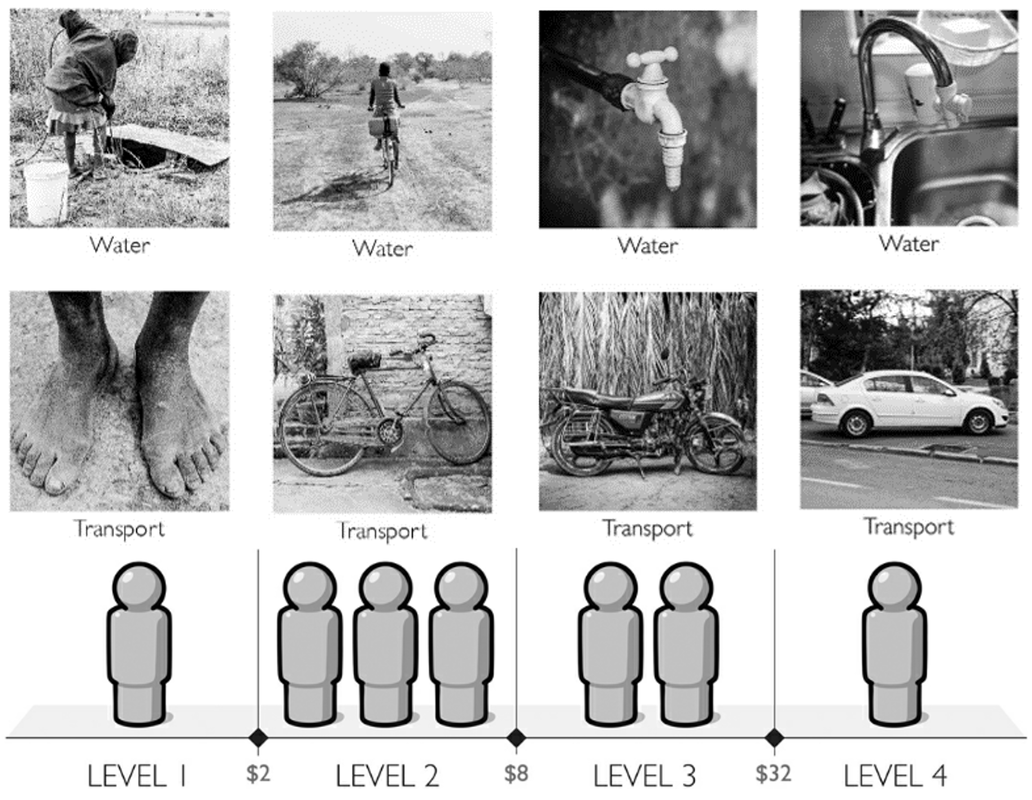

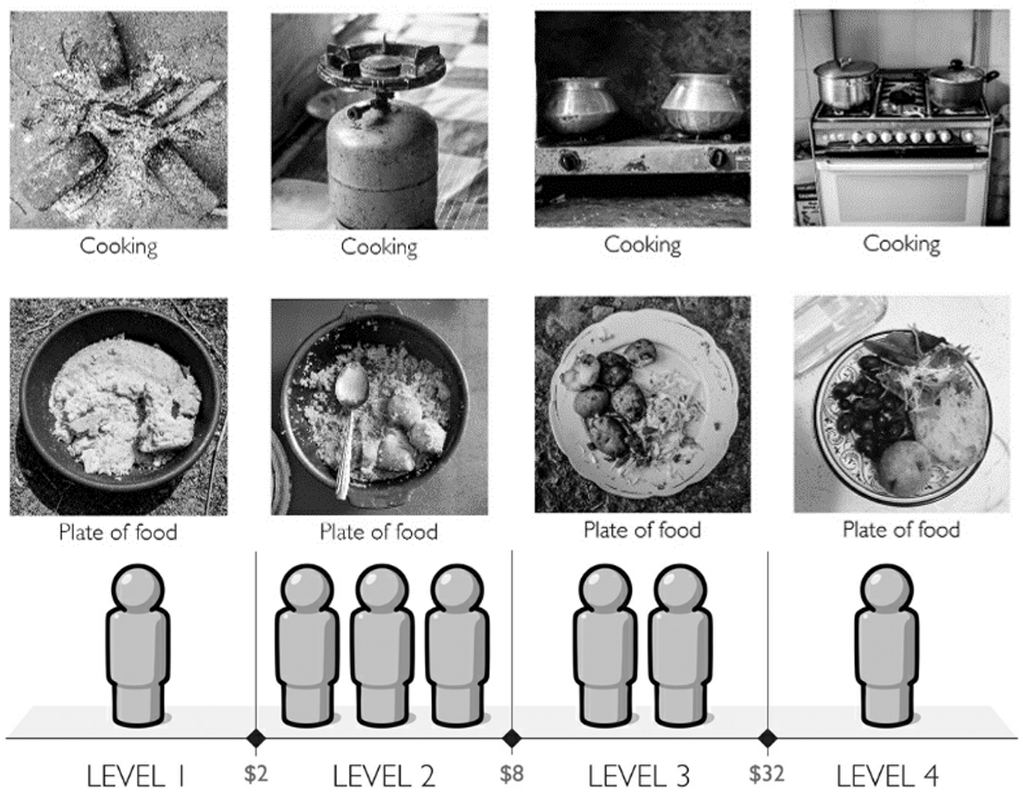

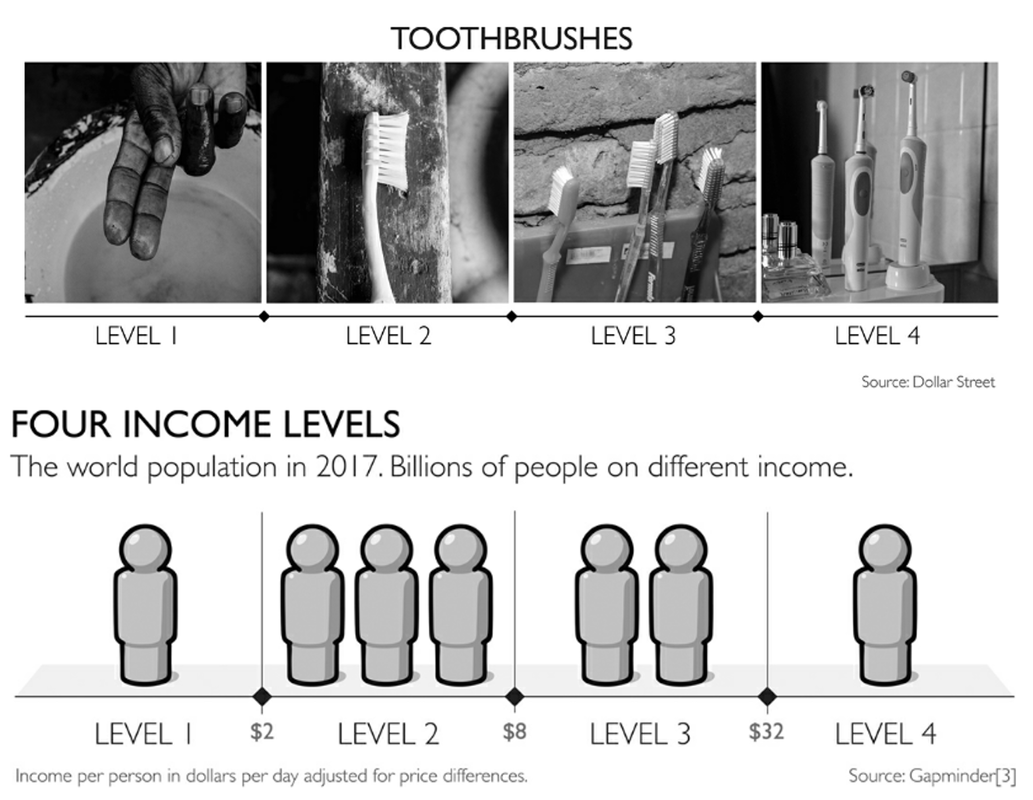

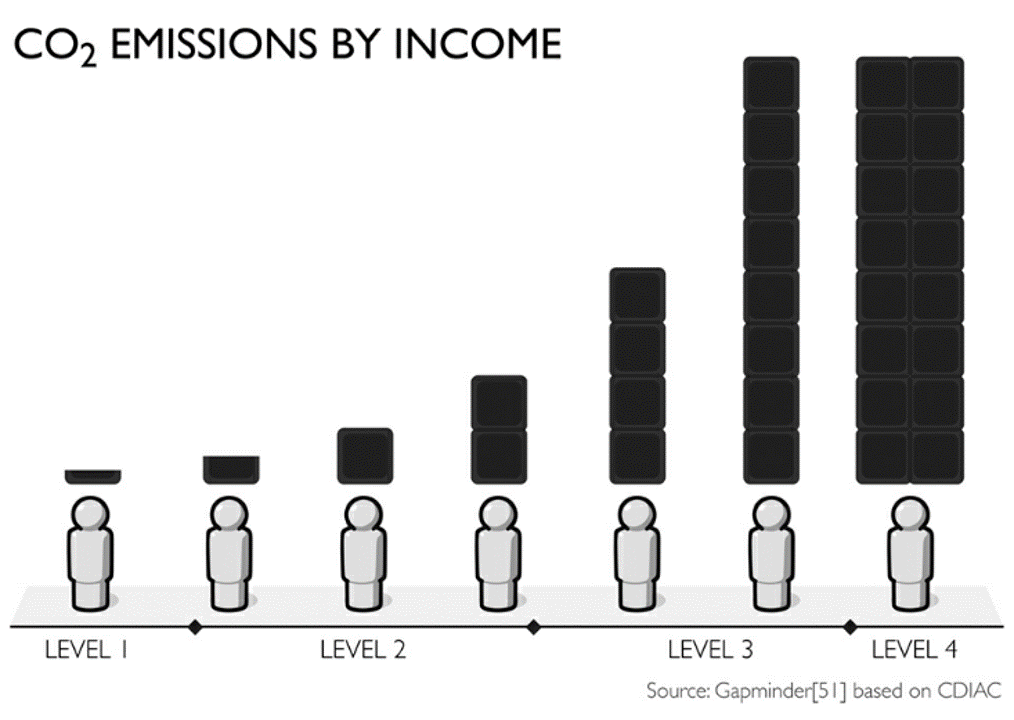

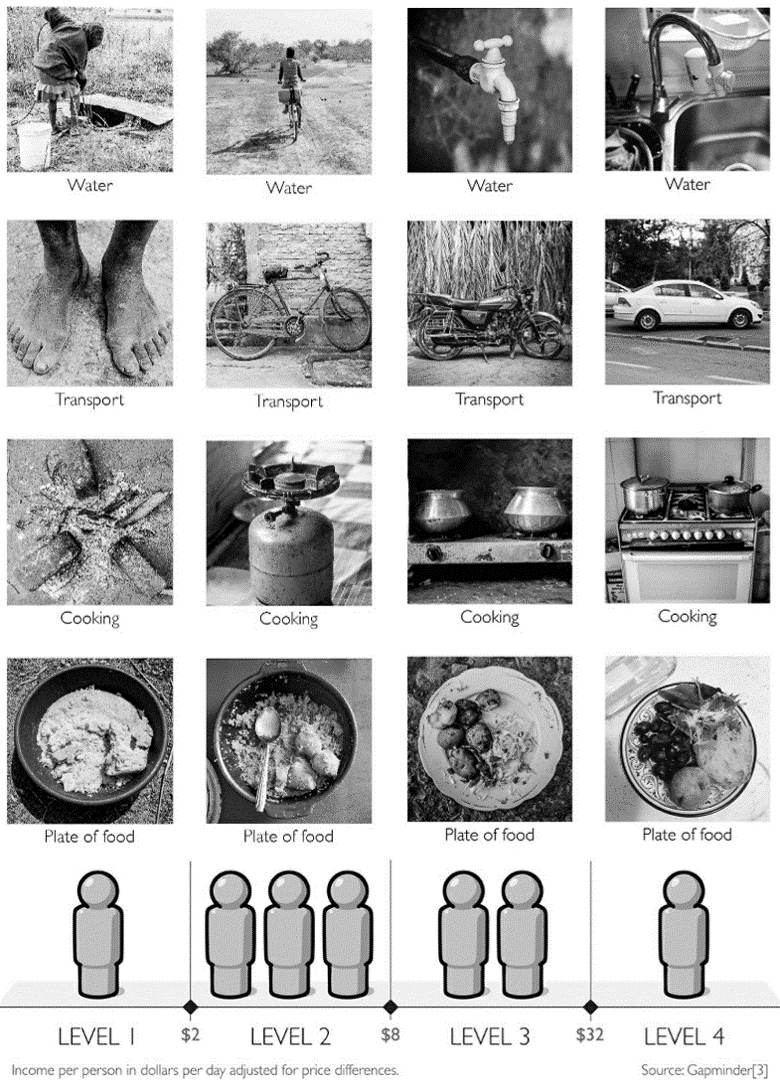

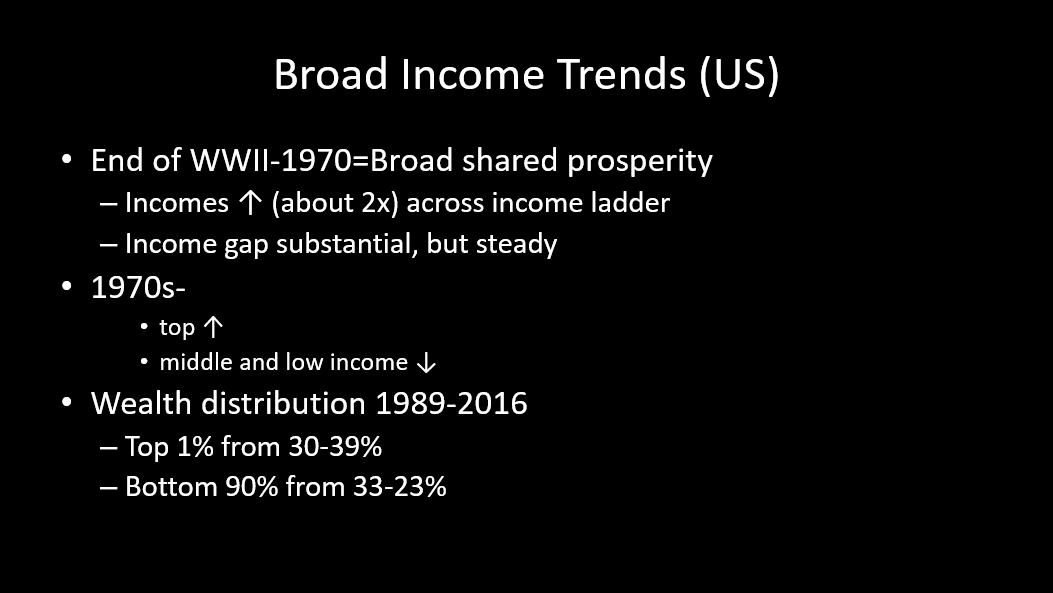

Scott AndersonNehemiah 8:1-3, 5-6, 8-10 † Psalm 19 † 1 Corinthians 12:12-31a † Luke 4:14-21 You’ve probably heard the one about lies and statistics. It’s a quote from Mark Twain, from about 1906 that he attributed to the British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli. Rather than repeat it here, let me just defer to a less colorful paraphrase of it from a letter to the editor of the British newspaper the National Observer: “Sir, —It has been wittily remarked that there are three kinds of falsehood: the first is a ‘fib,’ the second is a downright lie, and the third and most aggravated is statistics.”[I] Anyway, I found myself thinking about this, and about statistics in particular, as I was preparing for today, and trying to get a sense of what Luke is trying to claim about Jesus and his work in this text. Jesus stands up among his hometown folk and reads from Isaiah: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me,” And then the rest of it reads like a mission statement, which is, I think, Luke’s purpose. This, Luke suggests, is what Jesus is up to, what he is about, what God is doing in this promised one of unprecedented power and truth. “He has anointed me,” Jesus reads, to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”[ii] The passage is plain, and the work is straightforward, although it may take a little unpacking. But Old Testament scholar Walter Brueggemann, in his recent book Tenacious Solidarity is concerned that we may miss the plain sense of the text. Here’s why. He says: “we have been schooled, for a variety of reasons, to read the Bible in categories that are individualistic, privatistic, other-worldly, and “spiritual.”[iii] Now, he is getting old. Perhaps he’s worried about what he sees, as he nears the twilight of his long career and his life. But he makes a compelling case that we are prone to step away from the plain meaning of this gospel to our peril. Release to the captives, recovery of sight to the blind, freedom for the oppressed. Why would we read these in any way but literally, since these are the things that proceed to happen in Luke’s gospel? And the last one too: “proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.” That’s Jubilee, after all. That’s the story that runs through the law and the prophets that understands justice to require the forgiveness of debts. Again—a very literal notion that every 50th year all debts were to be cancelled. The slate was to be wiped clean. Indentured servants—slaves who were enslaved because they owed something were to be set free and what they still owed, forgiven, regardless of the amount. Brueggemann has a shorthand for this: economies of neighborliness, he calls them—economies that put people first, that look to the well-being of the whole, rather than a few, that attend to practices that give everyone the possibility to flourish. They stand in contrast to what we and most societies through history have also known, which he terms economies of extraction—"policies and practices,” according to Brueggemann, in which wealth is extracted from vulnerable people and transferred to powerful people, so that that wealth can be incorporated into their surplus holdings. Such extraction, accomplished by the force of government and of corporations, is characteristically legal, even if it is destructive and … immoral. Brueggemann goes on to note that the means for extraction are typically disguised, hidden from view with euphemisms and social and ideological coercion that conceals what is really happening.[iv] Once you begin to notice, it becomes obvious that much of our economy is tilted toward extraction. The signs are all over. This last week, for example, we learned that the world’s 26 wealthiest people now hold more wealth than the poorest 50%— 3.8 billion people.[v] This is not good for anyone. Statistics can be shaped to support all sorts of claims, of course. Especially when the question is so complex. You’ve heard me cite a more hopeful perspective, for example, from Hans Rosling.  In his book Factfulness, he noted that the world population is improving its lot, increasingly moving out of absolute poverty toward better standards of living. For example, Rosling reminds us that “Over the past twenty years, the proportion of the global population living in extreme poverty has halved.”[vi] Not only is this revolutionary, he asserts, but it reflects a dramatic reduction that continues a long global trend beginning with the industrial revolution. I suspect it’s worth a closer look at these seemingly inconsistent claims. Rosling is talking about global poverty. And his first point is that it does not serve us well to talk in either/or categories. The reality is usually far more complex. So rather than talking about rich or poor, Rosling wants us to talk about degrees of poverty and well-being. He identifies four levels of income that result in profoundly different standards of living for the seven billion people who now live on this blue marble of ours. You can see from this illustration the numbers of people, by billions, that currently live within these differing levels of income ranging from extreme poverty, which he considers as less than $2 per day, to relative wealth, which he pegs at above $32 per day. So, as of 2017, the best estimates are that about 1 billion of our siblings are living in extreme poverty, while about the same number of us live quite comfortably, with about 5 billion people living somewhere in-between. So what does this actually look like? Well, he helps us out with that as well, giving us some images that help us to visualize what that means when it comes to everyday life. How easy is it for you to get water for your daily needs, for example? What modes of transportation do you have available to you? The phrase we’ve heard for years from the CROP walk, for example—"we walk because they walk”—represents the reality of the poorest of the poor who must walk miles each day, just to get water, whereas others of us have an easier time of it. Likewise cooking and eating—the variety and amount of food we have available to us varies considerably among these four levels of poverty and wealth that characterize the 7 billion of us who share the planet and its resources. And then there are other ways of visualizing—both mundane and yet compelling—that help us to get a picture of our different life experiences. And the size of our footprint, when thinking about economies of extraction, is not equal. There are real implications when it comes to our access to things like transportation, power, and the like. So we begin to fill out our understanding, to see things in a more nuanced way that resists the binary thinking so encouraged by so many of our institutions, including, notably, the media. And one more thing before we try to broaden our understanding of the reality even more. Rosling’s website, which provides all sorts of great tools to help us see things with greater clarity provides a helpful visual narrative of our improved lot when it comes to health, wealth, and well-being among our world neighbors. At the risk of completely losing you we’re going to run this slide while I talk about it. Here you can see the movement out of extreme poverty for all the countries of the world since 1800. Circle size corresponds to population, so the circles for China—red, and India—aqua, for example, stand out because of their population size. You can also find the United States in yellow near the front of the pack. The continents are color-coded according to the graphic in the upper right-hand corner. You’ll see regressions that correspond to the world wars, and advances that correspond to periods of prosperity that occurred in the fifties and beyond. You can also see the dramatic movement overall through the income levels roughly demarcated at the top of the graph, clearly illustrating Rosling’s assertion that quality of life is improving overall among the world population. And while this is true, we know there is complexity here. Take for example other trends that are apparent as we begin to look closer to home, in our American reality in which most of us are comfortably situated in a level 4 level of living. While Rosling’s data generalizes in broad, national terms, we are also correct in our understanding that the divide between rich and poor continues to expand under current political and economic policies. This is where we get back to this statistics thing. According to the nonpartisan Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, there is a very evident turn that occurred in the 1970s, reversing trends that saw a growing prosperity shared among a broad spectrum of the population. Incomes generally doubled across the board over this period. This began to change in the 1970s and 80s in the West, and in the United States in particular. Income growth for households in the middle and lower parts of the distribution slowed sharply, while incomes at the top continued to grow strongly. The concentration of income at the very top of the distribution rose to levels last seen 90 years ago during the “Roaring Twenties” and, notably, before the worst economic downturn in the history of the industrialized world. And the thing is, this gospel of ours does not ignore these realities, but understands that the material and the spiritual together make up who we are. If our theology of incarnation is about anything, it is surely about this. And it recognizes that economies built around greed will inevitably fail, and everyone will suffer. This was true in the time of Solomon, and the reading in Nehemiah responds to the aftermath of just such a time with a renewal of economic policy and neighborly well-being. Brueggemann points out that one of the most significant books of our Bible is titled exit, or exodus. And it tells the story of salvation as a people exiting an economy of extraction, and God leading the way. Forgive us our debts, Jesus instructs his disciples to pray, as we forgive our debtors. This is economic language. It is neighborly language that understands that the ethics of this faith that Jesus taught are fundamentally neighborly.

The Bible lives amid various extraction systems. Yet, in its main contention, the Scripture does more than live among them. It responds to them in various forms of resistance. It refuses to accept the fiction that sustains them, but instead speaks truth into them: The economy, after all, is a human construction, and it can be ordered differently. Endless acquisition evokes endless anxiety because once we go down this road of greed, we can never have enough. And it offers daring proposals for an alternative economy. This faith of ours understands that there is another way. A better way, a life-giving alternative that is possible. It’s not an economic theory. It is this way of neighborliness Jesus proclaimed, and its promise of life to the full as we give ourselves to it. Amen. Notes: [i] Wikipedia: “Lies, damned lies, and statistics”. Retrieved on January 25, 2019 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lies,_damned_lies,_and_statistics. [ii] Luke 4:18-19. [iii] Brueggemann, Walter. Tenacious Solidarity. Fortress Press. Kindle Edition (Location 891). [iv] Brueggemann, Walter. Tenacious Solidarity. Fortress Press. Kindle Edition (Location 966). [v] The Guardian. “World’s 26 riches people own as much as poorest 50%, says Oxfam” Retrieved on January 22, 2019 from https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/jan/21/world-26-richest-people-own-as-much-as-poorest-50-per-cent-oxfam-report. [vi] Rosling, Hans. Factfulness: Ten Reasons We're Wrong About the World--and Why Things Are Better Than You Think (p. 6). Flatiron Books. Kindle Edition.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed