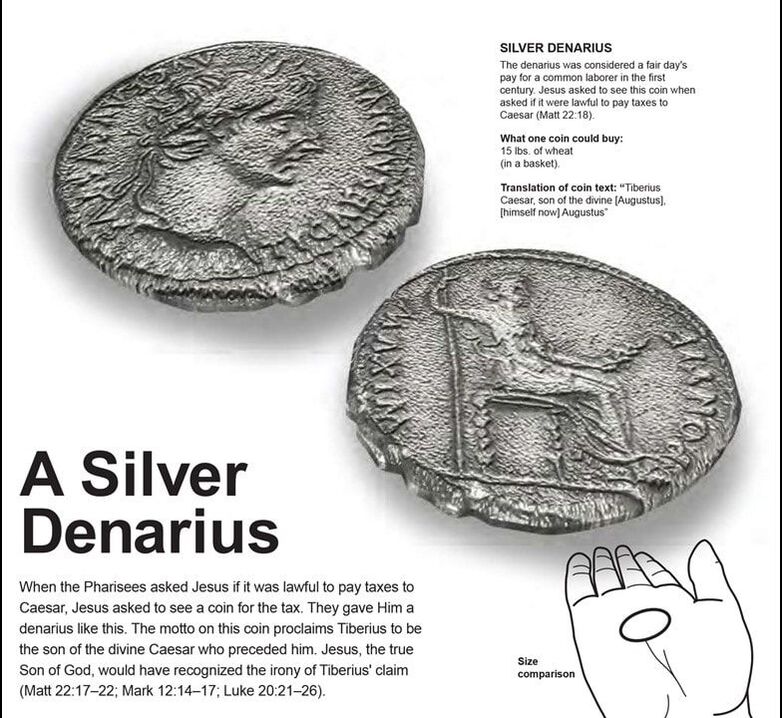

Scott AndersonIsaiah 45:1-7 † Psalm 96:1-13 † 1 Thessalonians 1:1-10 † Matthew 22:15-22 A video version of this sermon can be found in the context of online worship here. We know from the outset that there is no good will here. Matthew tells us at the beginning that the Pharisees are out to entrap Jesus. They are looking to take him down. They are not seeking truth. They are long past that point. They are out for blood. And we know well enough they will soon get it. And they form a strange alliance to set their trap. Now, we don’t know much about the Herodians in the Matthew text, but their name suggests they are loyal to Herod. They are not religious; they are political—Roman partisans. They see the heavy hand of Roman rule on the Jewish people as justified, which puts them in opposition to the large population of Jerusalem that bristled under ongoing Roman occupation and rose up in popular armed rebellions on both sides of this story. So let’s just say there is some tension here. I suppose we might know a thing or two about that. Now, the Pharisees are in no way happy about Roman occupation. They had decided it was a tolerable evil as long as Rome didn’t step on the church’s freedom—and the power of these privileged leaders to operate within it. The Pharisees objected on religious grounds to the coin, the denarius that was produced which had an image of “the divine Caesar” on it, at least a violation of the first two commandments against other gods and graven images. And yet, here it was, easily found within the temple walls—things rendered to Caesar and things rendered to God comingled on the most holy ground. That someone was able to produce the coin so easily points to the corruption of the system that was in place. So the trap is set. If Jesus says don’t pay the tax, then they can accuse him of sedition—just another middle-easterner out to destroy this great empire—and Pilate can send him to Guantanamo. If he supports the tax, which was a huge burden on the people and a symbol of their oppression, then Jesus is going to lose some of the populist base that just welcomed him into Jerusalem on that donkey. The trap is set, but Jesus astonishes. His answer is both confounding and compelling. “Give to the emperor what is the emperor’s and to God what is God’s.” It caught me that this is one of the few times that Jesus doesn’t answer a question with another question. But he might as well have, because the answer only raises more questions in the story, and importantly, for us. He not only evades the trap that was laid for him; he throws the issue back at them, and onto us. Now we who may have been in the stands rooting for one side or another are suddenly down in the playing field. We are faced with a lion of a question: what does belong to Caesar and what belongs to God? Jesus offers thinking words. He cuts through the middle of this toxic partisan reality and compels us to move beyond our settled perspectives, to consider again what core values shape us. Suddenly we find ourselves checking the ways in which we have become so preoccupied with partisan concerns, with goals so narrow that we are willing to sacrifice all manner of other principles in order to achieve them. Jesus’ response does more than just outwit his opponents. The coin bears Caesar’s image on it, which reminds them that humans—all humans—bare the image of God. They may pay the poll tax that Caesar demands, but they are not Caesar’s and they never will be. They belong to God. And so do we. And so does our neighbor, and so does the earth. God and the emperor are not equals, as Isaiah’s astonishing poetry suggests. Isaiah claims God’s power even to use unwitting outsiders for God’s purposes. That’s what’s going on with Cyrus the king of Persia who was the conqueror of Israel’s conqueror. Cyrus takes down the Babylonian empire which had taken much of Israel into captivity and makes way for their homecoming. Cyrus, who is no worshiper of Israel’s God is claimed as God’s instrument, God’s anointed, God’s messiah.

Now, I don’t know about you, but for me, this notion creates as much trouble as it resolves. There are all sorts of dangers to claiming to have God in our pocket. And everyone seems to be doing it these days. And yet we can cling to the promise that there is always more going on than we are aware of, the broader claim of the shepherding embrace of an engaged God who is Love. What we cannot now perceive as in any way “divine” might just belong to the providential plan that leads to our salvation. God’s ways remain just as inscrutable to us as to anyone else. And there is this: a thread that runs throughout the biblical story of an ever-expanding circle of God’s saving good will to more and more people. Consider just the Isaiah texts in the last few weeks. What began two weeks ago as a parochial, garden variety household—a vineyard that grew wild grapes in Isaiah 5 expands to include the banquet table we encountered last week for all people on the holy mountain in Isaiah 25, to include God’s saving act through an agent that is not only outside of the household of faith, but possibly completely unaware of it in today’s text, and is yet drawn into the inner circle of God’s purposes.[i] God and the emperor are not equals, and they are not symbolic names for separate but equal realms. The force of the story is quite the opposite: humans bear God’s image, so wherever we live, wherever we operate, whether it is in the social, religious, political or economic realm we belong to God. The earth is the Lord’s and everything in it. And everything that we do follows from this premise. Make no mistake: this is good news. So what does it mean to belong to God? What is God’s then, and what is Caesar’s? This was a particularly important question for many German Christians as they watched the rise of Hitler’s administration as it grew increasingly friendly with a segment of the German church. It was enough of a concern that they wrote about it in what came to be known as the Barmen Declaration—one of confessions. They wrote this: As Jesus Christ is God's assurance of the forgiveness of all our sins, so in the same way and with the same seriousness is he also God's mighty claim upon our whole life. We reject the false doctrine, as though there were areas of our life in which we would not belong to Jesus Christ, but to other lords.[ii] Barmen echoes the claim that all things, all areas of our life belong to God. And yet, it is unmistakable that we who belong to God must live and engage in a world filled with others who belong to God. We pay taxes within it that either help or hurt our neighbor who belongs to God. We take out mortgages or we are denied home ownership and the building of wealth by policies that affect all who belong to God unequally. All people belong to God whether they are housed in mansions or emergency shelters or cages, whether we dismiss them as outside the realm of God’s household or inside. Render to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to God what is God’s. This is no simple task, but a constant and holy working out of how we live, what we value, whom we support, and how we bear the image of Christ from one moment to the next. This is the work of those who are called to be imitators of Christ. And it is everything. Thanks be to God. Notes: [i] Feasting on the Word: Year A, Volume 4: Season after Pentecost 2 (Propers 17-Reign of Christ) (Feasting on the Word: Year A volume). Presbyterian Publishing Corporation. Kindle Edition. [ii] Barmen Declaration 8.14-15.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed