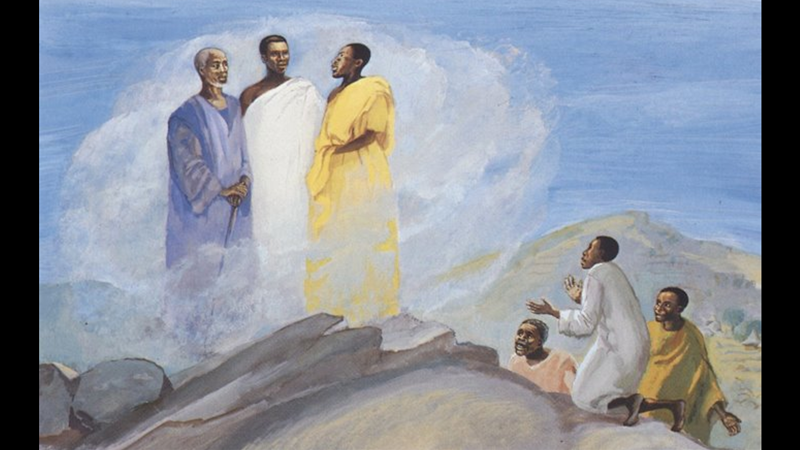

Scott AndersonExodus 24:12-18 † Psalm 2 † 2 Peter 1:16-21 † Matthew 17:1-9 When you are out in the wilderness and you see a big cloud coming, you start to look for shelter. You don’t need to be an expert hiker to know this. You feel it first. This is especially true when you are up high and exposed. Conditions can change in an instant, and if you are not prepared, you can find yourself in danger far more quickly than you would imagine down here near sea level, among the trees. And yet, many of us—especially in this region—are drawn to the mountains and the wilderness and the unknown, despite the inherent dangers. We are looking for something, it seems, that we do not regularly encounter. We are seeking something that cannot be readily obtained in the ordinariness of our day-to-day lives here in the lowlands. “I’m drawn to places,” writes Eric Weiner, “that beguile and inspire, sedate and stir, places where, for a few blissful moments I loosen my death grip on life, and can breathe again.”[i] Heaven and earth, the Celtic saying goes, are only three feet apart. Yet these ancient seekers knew that in some places—they called them “thin places”—the distance is even shorter. There is something about these places. You feel it when you’re there. And they are everywhere. Like up near Lake Tipsoo on the edge of Rainier National Park and the mountain the early settlers of this land knew as Tahoma. They are a common reality in the Pacific Northwest—a draw to many who would rather spend their weekends heading for the hills and the mountains and the oceans and the streams than spend them in low-slung church buildings.  It does make sense, of course. There’s something here that lifts our spirits, that opens up our imagination, that fills us with elation, that not only makes us dance, but simultaneously draws us to the edge, that wells up within us an awe and wonder that we just don’t find many other places. It’s the beauty of it, but its more, isn’t it, that brings heaven and earth even closer? So much that draws us out is a draw to our limits, to a tree-top or to a precipice where we fight vertigo in order to peek over the edge, an encounter with a power that is bigger than our own, a grandeur that can swallow us up. I understand that before there was Christmas, before there was Easter, even, there was Transfiguration in the early church. If this is true, if the celebration of this story which we find all over the scriptures—paralleled in Matthew, Mark, and Luke, and referenced in our 2nd Peter reading—predates the institution of those more dominant stories[ii], then there was and perhaps there is something to pay attention to here—a thin place in this reading that harkens back to Moses’ encounter with God, and Elijah’s, and the common link they all have to the core truth of our life as creatures on earth, made for justice, drawn to peace, where the question of who we are and who we are to be is called into fine focus, where the limitless and the limited confer, where a cloud of mystery and a voice from the heavens just might reveal something about our everydayness that we cannot survive without. I suspect there’s something here that’s not just about our wanderlust. I suspect these stories, and this recurrent theme of the encounter of God in the far-off, desolate and dangerous places—on the edges—by those who are looking for a life that makes a difference for all, that matters at its center, has everything to do with learning to trust God in our most profane moments—waking from the slumber of lives that have lost their center, where kids in cages have ceased to offend our senses, perhaps, or the obscene distances between haves and have nots no longer scandalize us. Where we have lost sight of the unique importance of your life and mine, where we have lost our voice, or begun to imagine we are expendable or unnecessary. In a sense, this is precisely the work of Lent, and why these stories and this Transfiguration Sunday have been placed at the beginning of it. During this season the stories and texts and poetry we encounter invite us to ask about our true home and our place among it. It is worth noting, I suspect, that the terror of the disciples doesn’t come with the transfiguration of Jesus. Their terror is not caused by the mysterious presence of these two giants of the faith—Moses and Elijah—who represent the fullness of the religious tradition in this thin moment. It doesn’t even come with the sudden arrival of the cloud and all that it obscures and threatens, much like it did the Israelites below who watched the cloud envelop Moses on that mountain. In fact, Peter seems thrilled, elated even. “This is great!” he says. It is so good we are here. We can build some shelters. We can construct tabernacles, just as the ancient Israelites did every year, to commemorate our emancipation from slavery in Egypt, to remember how God sheltered us when we were most exposed. And he’s not wrong. It’s just that he isn’t right either. By the way, I love the way the text treats him. It seems pretty clear he is missing the point, getting himself caught up in a moment that is not about him, but about something sublime, essential, and pivotal. But nobody shames him. Nobody shushes him. The story simply moves forward with singular focus toward what truly matters. It’s not a bad model of the ways in which we might be with each other with grace and purpose. The moment of terror for Peter and James and John comes with that voice. Verse six tells us, “When the disciples heard this, they fell to the ground and were overcome by fear.” It is the voice that reminds them of where they are and who they are. It is the voice that says, this is my son. Listen to him. Listen to him. And immediately, Jesus touches them. Immediately he is there with the simplest of physical acts. Here is something tangible and real that once again settles them. The story ends with grace. Jesus touches them as he did the leper, as he did Peter’s mother-in-law, as he did the two blind men. He speaks words of reassurance and says follow me. And we are invited into that deep unknowing, that deep mystery that promises us that at that very point that we find ourselves at our limits, as we lose ourselves and are engulfed in this fiery truth that holds us, that our lives just may begin to mirror the glory of God.

So there is this strange tension here. We long for those limits that bring us to the edge of our creatureliness. They are, for whatever reason, tied to our best living. Yet these thin, ethereal moments are forever dependent on the most ordinary and mundane aspects of our lives as well. You have heard me say before that the church is not the means of salvation. The church does not save. If transfiguration teaches us anything, it is surely this. The church simply points to what does, to that which is beyond, yet always in our midst. God saves, but the church and our lives in it exist as a sign of salvation. I don’t know about you, but I find this less than satisfying at times. I have a love-hate relationship with the church and the strange experience we have within it of this imperfect community that both draws and frustrates us. Here we are, a populous of decidedly imperfect people. Yet it is what we have that is tangible, that fills out those limit experiences, those thin places with touch and sound and materiality and generosity that is seen and heard—water and fire and bread—measurable and quantifiable and ever astonishing for its unexpectedness. Paradoxically, the place of fearfulness—the place of risk—is also, the place of being known and loved. For whatever reason, we are continually lured by God, through increasing levels of obscurity and vulnerability, to a deeper knowledge and love. So Transfiguration Sunday and the Holy it points to offers us a gateway to this work, which is accentuated in Lent as we move toward the edges of our lives to glimpse just what God might be up to. Amen. Notes: [i] Eric Weiner. “Where Heaven and Earth Come Closer” in the New York Times, March 9, 2012. Retrieved March 2, 2019 from https://nyti.ms/2jE0b5N. [ii] Cf. Matthew 17.1—8; Mark 9.2—8; 2 Peter 1.16—18.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed