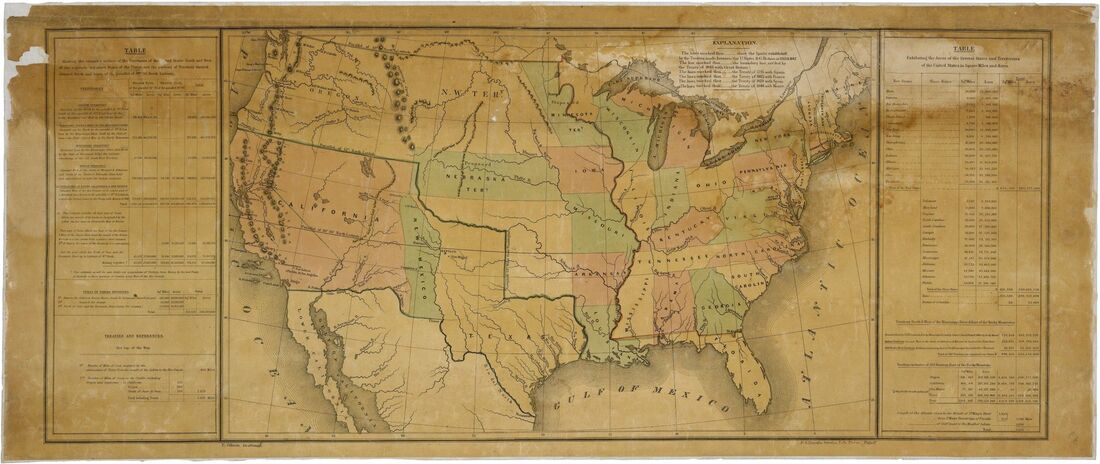

Scott AndersonActs 17:22-31 † Psalm 66 † 1 Peter 3:13-22 † John 14:15-21 If you get the environment right, every single one of us has the capacity to do remarkable things. Not only that, if you get the environment right, good deeds breed good deeds. When the conditions are right, safety, self-sacrifice, mutual love all increase exponentially. Generosity evokes further generosity. We’ve certainly seen that of late with your remarkable generosity toward this community and the church’s work within it. It builds on itself. Advocacy breeds further advocacy. An advocate shapes an environment of mutual support. Advocacy gets the environment right. In John’s story Jesus speaks of the Spirit as an advocate. “If you love me, you will keep my commandments. And I will ask God to give you another Advocate to be with you forever.” Our Christian tradition understands this in a Trinitarian sense—that the Spirit of God in Christ is now with us forever as an advocate—a force of love absolutely and undeniably for us and for our corporate well-being. A force that abides in the very heart of God. It didn’t start with the Spirit, of course. Jesus, in his very life has been an unflinching advocate for these disciples and for those who will follow. He is for them, giving of himself, showing them the way by his example, washing and kissing their feet, loving them to the end. He was there, listening deeply to the story of the hemorrhaging woman, and to the woman at the well—drinking in her story and letting it shape his own life. He was the one who saw in others such a measureless value that he forgave them even when they crucified him. Jesus, the advocate sent to us another advocate, and in so doing modeled for us that advocacy is the very shape of the Christian life. This notion of advocacy is an especially important one, I think, for the church in this time. As we navigate a life-altering pandemic, the tattered edges of our life together are becoming clearer. We are being invited to a reckoning, to ask, as Lainey Sickinger helped us to do last Tuesday in our Zoom discussion, to consider what we are learning in this time—what we want to let go of, what we want to hold onto, and what we want to reach for. I am reminded of a phrase Timothy Egan uses in his 1998 book Lasso the Wind to describe the American West and the forces that continue to shape it: “They use a false view of history to disguise most of what they are up to.”[i] I am chastened by it, because it could refer to much of what we are being invited to notice these days: I had heard too many lies about the “Real West,” flimflam and fraud retold as gilded narrative by people whose grandparents took the land by force and have been draining the public trough ever since to keep it locked in a peculiar time warp of history.[ii] Egan uses the chapters of his 1998 book to allow these complex stories of the American West to make his point, but for us today, in the context of these scriptures, the idea speaks to the polar opposite of advocacy, and to one of the big strategies by which those who have the power seek to maintain and expand it at the expense of others. And it speaks to the truth-telling that is required of us if we are to be advocates in the way of the One who said to his disciples, “They who have my commandments and keep them are those who love me.”[iii] First Peter says, “It is better to suffer for doing good…than to suffer for doing evil.” While we surely would prefer to eliminate suffering, this sentiment rings true in a way we might not first recognize. We think of the idea of justice as outcomes that correspond to our actions. So, we might think that suffering for doing evil is better, because it is “just”—appropriate punishment, if you will. While suffering for doing good is surely unjust—because you don’t deserve it. Yet at the heart of this Gospel of ours is the clear understanding that Jesus was punished for his good works, for calling out what was unfair, for pointing to the damage people and their systems were doing to all of creation and its creatures, even if the governments and religions of the day didn’t want to hear it. Even as they punished him for it, while claiming the moral high ground. At the heart of our story, in other words, is the clear message that Jesus came to expose those who “use a false view of history to disguise most of what they are up to.” But that is only the beginning. It was for a larger purpose. It was to replace these kingdoms with a new Kingdom, these forms of government with a new governance that promised life to the full for everyone, not just a few. So First Peter understands it is better to suffer for doing good because—even though it is unjust—that suffering can be the catalyst for changing everything, for renewing the earth, for saving our lives. That kind of suffering has the power to eliminate suffering, to atone for it. Let me see if I can offer a few examples to illustrate this. Egan gives us the first as he reminds us of the history of the West. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed in 1848 brought an official end to the Mexican-American War and transferred over 50 percent of Mexico’s territory—which included parts of present-day Arizona, California, New Mexico, Texas, Colorado, Nevada, and Utah, to the United States. That’s when the Rio Grande became the southern boundary of the US. As a part of the deal, Latino ranchers and livestock herders of newly American New Mexico were assured that their land grants would be preserved. But it was a “hazardous legal hike” according to Egan. Going through unfamiliar and distant American courts to assure ownership of land handed down from a Spanish monarch or a Mexican general would never be easy.

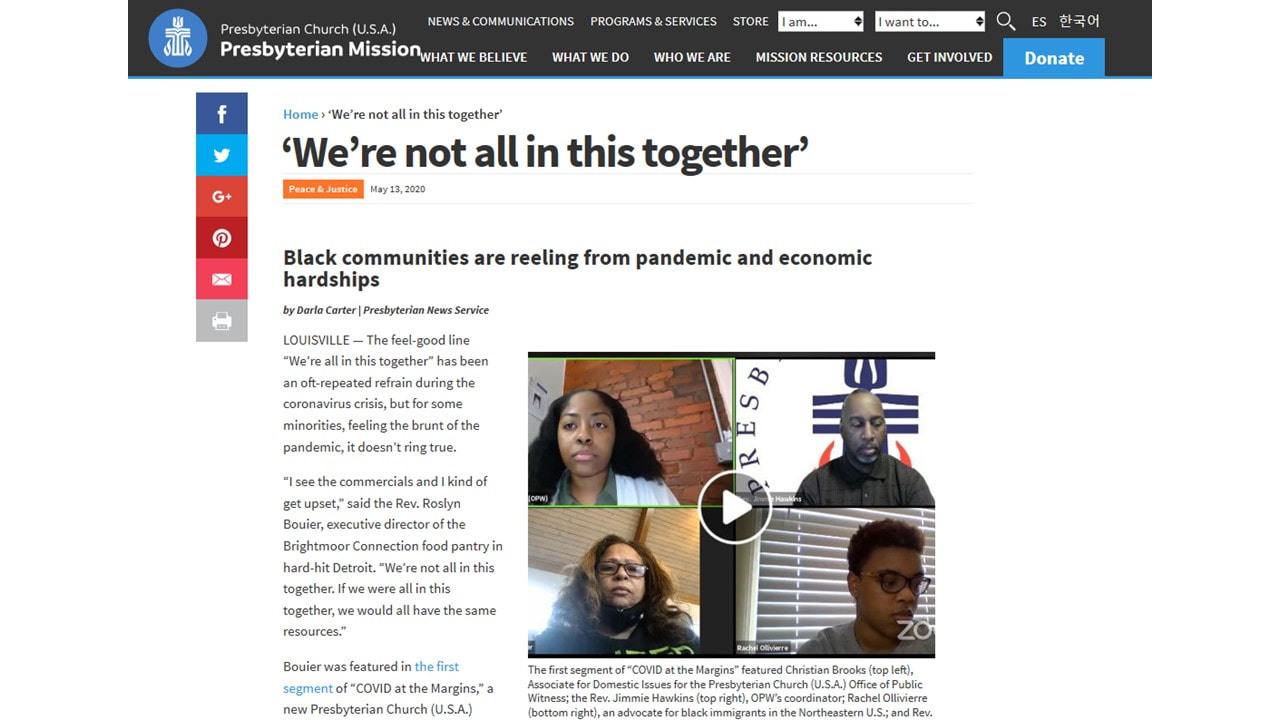

So while maintaining the moral high ground, and through entirely legal means mind you, Catron robbed the ordinary people who had been tending the land in community for centuries and added another stone to the path for the exploitation and draining of public lands ever since. Egan recites this particular part of history while on his way to Diamond Bar Ranch, a plot of land with nearly 150,000 acres in the Gila National Forest. That’s where Kit Laney and his wife Sherri were trying to raise cattle. They used to pay $22,000 a year to run his cattle on public lands. But then they stopped. They live in a little place without electricity. Kit hauls water and cuts wood for the stove. They raise pigs, milk cows, and make their own butter and bacon. “I’m fourth-generation Catron County, so’s Sherri,” he tells Egan. “We were both born here.”[v] Egan explains: The way Laney figures it, he owns the right to use the water that runs through the section of the Gila where the cattle graze. If the government wants water to keep the public forest alive, they will have to pay him for it. “I’m saying to the Forest Service, ‘You guys don’t own this water.’ And they may not even own the land. They never have been able to produce a title document. This story from over 20 years ago sounded familiar so I did my own digging, and found that Laney’s story was one in a line of many that linked to Aamon Bundy on the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge and a host of ranchers throughout the West who have protested what they see not as public subsidies from which they uniquely benefit, but as federal overreach in their regulation of public lands. There is, it seems, an age-old tradition of seeing the west as a birthright. This is not a crackpot idea. It has a logic to it, although it may be a conveniently short-sighted or false one. That’s what Egan is arguing in the book. He sets up this story in the context of describing a history that long precedes the arrival of white settlers to the land. The Gila Cliff Dwellings near Kit Laney’s Diamond Bar Ranch tell the story of the Mogollon people who had lived in the region for over 1400 years, dating back two centuries before the common era. He reminds the reader of the many ancient civilizations who lived on the land with arguably much more right to it, by Laney’s standards, not to mention much more advanced notions of civility before they were murdered, run off, or relocated by government treaties that proved time and again to be faithless. Egan offers a summary of just this one chapter in the story of the West and this “false sense of history that disguises most of what we are up to”: Every cycle produces new victors and new victims. The constant is the government—always the target. They wrote and broke treaties with virtually every native group in the West. They dammed the great rivers, paid bounty hunters to kill much of the wildlife, and auctioned off the forests. Now, as they try to make amends, they wonder why nobody trusts them.[vi] How we need advocates. And how we suffer without them. Yet there’s a lesson here for the church about what advocacy looks like. It can never be simple-minded, imagining that good deeds alone will fix what goes deep—a false sense of history, say, that disguises most of what we are up to. Our advocacy requires a deeper knowing that looks with a critical eye at the stories we tell ourselves. That’s what Ahmaud Arbery’s story is about, and Trayvon Martin’s, and Emmett Till’s, and more black men than we can count. Racially discriminatory housing, employment, and public health policies are all part of the system of white supremacy that has long existed within our country and our church. And to keep the commandments of the One we profess to love, to advocate as God advocates means to look deep into the eyes of these who suffer and the stories they have to tell and to learn from them how to reshape our world in ways that sustain all of life, not just some. So we need creativity. And we need to think systemically. Slavery was once legal. Black Codes and Sundown towns and sharecropping were legal. Jim Crow was legal. Racial covenants were legal. Mass incarceration is legal. We need to expose those laws and those systems today that continue to tell a false sense of history that disguises most of what we are up to. The Rev. Roslyn Bouier called out one of these disguises recently. “We’re not all in this together” she said, countering the frequently repeated phrase of this coronavirus crisis. “We’re not all in this together. If we were all in this together, we would all have the same resources.”

But we can be, if we get the environment right. If we give ourselves to the advocacy of the one who advocates for us. If we follow the commandments of the One who loves us. Amen. Notes: [i] Egan, Timothy. Lasso the Wind. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. [ii] Ibid. [iii] John 14:21. [iv] Egan, Timothy. Lasso the Wind. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. [v] Ibid. For other background, see, for example, this article and video from January 4, 2016: “Kit Laney Rides No More on the Diamond Bar Ranch”. Retrieved on May 15, 2020 from: http://www.sustainingamerica.com/2016/01/04/kit-laney-rides-no-more-on-the-diamond-bar-ranch/. [vi] Ibid.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed