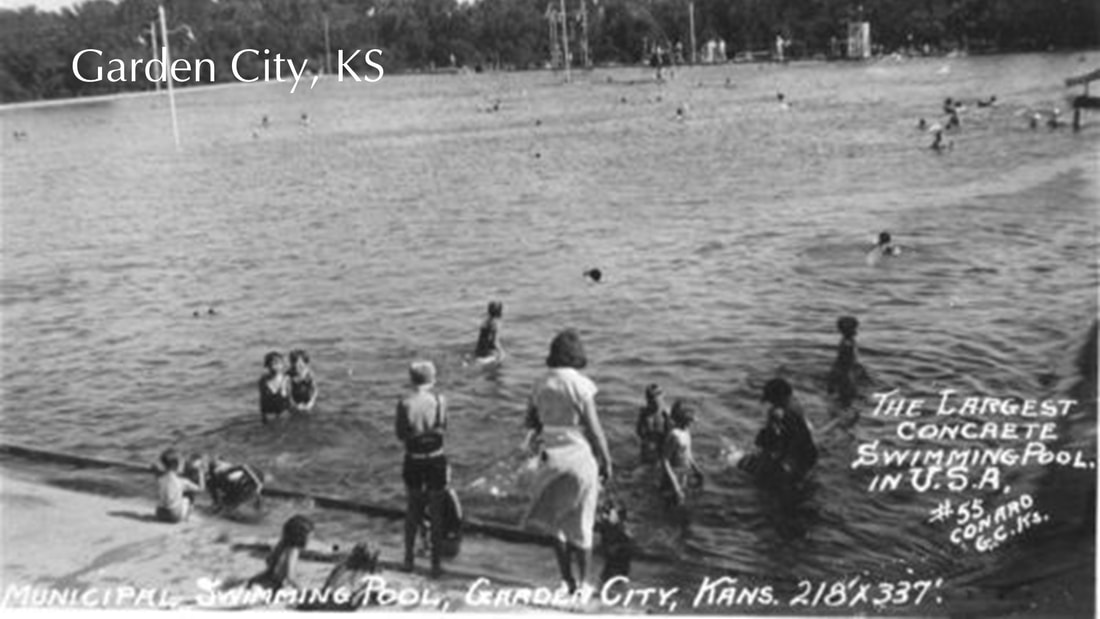

Scott AndersonGenesis 17:1-7, 15-16 † Psalm 22:23-31 † Romans 4:13-25 † Mark 8:31-9:1 A video of this sermon is available here. In the 1920s and 30s, towns and cities across the United States tried to outdo one another in building thousands of magnificent public swimming pools for their communities. They were often enormous and elaborate—community gathering places built for a rapidly expanding middle class to enjoy together. There was the Big Pool in Garden City, Kansas. Dug by hand and opened in 1922, the bath house and wading pool were added by the WPA in the 1930s. Elephants from nearby Lee Richardson Zoo swam in it after it closed for the season. In the 1980s in a promotional stunt, two Garden City youth skied on the pool to promote Finnup Park, Lee Richardson Zoo, and the world’s largest outdoor free concrete municipal swimming pool. The pool is currently closed for another face-lift with plans to reopen for a grand centennial celebration. There were others, though, that did not survive. Oak Park Pool and its shimmering facilities in Montgomery, AL were part of the first wave of investment into public pools. The pool was the grandest for miles, a crown jewel of the Parks Department. But it was only for whites. In 1953, Tommy Cummings, thirteen, drowned in Baltimore’s Patapsco River while swimming with three friends, two white and one Black, like Tommy. He was one of three Black kids to die that summer in open water. The NAACP successfully sued the city and three years later, for the first time, all Baltimore children had the chance to swim in the public pools with other children, no matter the color of their skin. Heather McGhee tells the story in her new book The Sum of Us. “Public recreation free from discrimination could, in the minds of the city’s progressive community, foster more friendships like the one Tommy was trying to enjoy when he drowned.”[i]

Sadly, this is not what happened. Instead of sharing the pool, white children stopped going to pools that were easily accessible to Black kids. And white adults, through intimidation and violence, policed public pools in white neighborhoods to ensure they would remain segregated. In smaller towns where there was only one public pool, that strategy wasn’t going to work, though. As Black community members pressed for access to the public resources their tax dollars had helped build, towns throughout the country tried all sorts of maneuvers to resist desegregation. They took public assets private, for example. In Warren, OH, they created the members only Veterans’ Swim Club and selected members by secret vote. Only white members were selected. In Montgomery, West Virginia a sparkling new resort pool built in 1942 lay untouched for four years while Black residents argued for equal access. The city eventually formed a private “Park Association” to administer the pool. The city leased the public asset to the private association for one dollar. Only whites were allowed. The Oak Park Pool in Montgomery, AL suffered a different fate. When a federal court deemed the town’s segregated recreation unconstitutional, rather than allow children of color to swim with white kids, rather than give a seat at the card tables in the rec center to Black elders, the city council closed the Parks Department and they drained the pool. Here’s McGhee again: Uncomprehending white children cried as the city contractors poured cement into the pool, paved it over, and seeded it with grass that was green by the time summer came along again. To defy desegregation, Montgomery would go on to close every single public park and padlock the doors of the community center. It even sold off the animals in the zoo. The entire public park system would stay closed for over a decade. Even after it reopened, they never rebuilt the pool.[ii] McGhee chronicles the casualties: New Orleans closed Audubon Pool in 1962. A real estate developer unearthed the old segregated pool in Stonewall, MS[iii] some 15 years ago. Racial hatred and violence finally led to St. Louis draining Fairground Park Pool, one of the most prized public pools in the world.[iv] McGhee contends the building of thousands of pools, was a symbol of something distinctly American—the investment not just in infrastructure, but in people, in working toward a vision of prosperity and well-being and quality of life in a richly diverse society: …public pools were part of an “Americanizing” project intended to overcome ethnic divisions and cohere a common identity—and it worked. A Pennsylvania county recreation director said, “Let’s build bigger, better and finer pools. That’s real democracy. Take away the sham and hypocrisy of clothes, don a swimsuit, and we’re all the same.” Of course, that vision of classlessness wasn’t expansive enough to include skin color that wasn’t, in fact, “all the same.” By the 1950s, the fight to integrate America’s prized public swimming pools would demonstrate the limits of white commitment to public goods.[v] McGhee is asking why we work against our own best interests, why we deny ourselves things rather than allow others to enjoy them. Why can’t we have nice things? And by nice things, she is thinking of public goods, basic aspects of a high-functioning society: “adequately funded schools, reliable infrastructure, wages that keep workers out of poverty, public health systems to handle pandemics.”[vi] She charts a steady decline in public investments that began with Civil Rights legislations that takes us right to our front door, to the economic prosperity we kept hearing about right before COVID. But the prosperity has a different footprint than it did when these pools were filled. Here’s the data from 2020: 40 percent of adults were not paid enough to reliably meet their needs for housing, food, healthcare, and utilities. Only about two out of three workers had jobs with basic benefits: health insurance, a retirement account (even one they had to fund themselves), or paid time off for illness or caregiving. Upward mobility, the very essence of the American idea, has become stagnant, and many of our global competitors are now performing far better on what we have long considered to be the American Dream. On the other end, money is still being made: the 350 biggest corporations pay their CEOs 278 times what they pay their average workers, up from a 58-to-1 ratio in 1989, and nearly two dozen companies have CEO-to-worker pay gaps of over 1,000 to 1. The richest 1 percent own as much wealth as the entire middle class.[vii] It is important for us to understand what Jesus seems to understand this call to self-denial, to taking up one’s cross means. As we know too well, this is a word often beaten over the head of those who already suffer at the hands of injustice and abuse. There is a distinction between this kind of suffering—that come due to abuse of power and the results of inequity and white supremacy and immoral legislation—and the suffering that we take on when we resist these forms of injustice. It is the second Jesus speaks of, the second that Jesus invites us into as disciples. Jesus resisted, nonviolently, the social evils that denied and deformed human life. He sought liberation for the marginalized and outcast. The suffering Jesus imagined would come as a response to our resistance in all that threatens what God has created—the consequences of the rejection of those who only serve self. To put it differently, humans, not God, are the source of suffering. Humans are the crucifiers. And if we are to be disciples of this one, then we, like him, will name and resist evil as he did, even as we may find ourselves paying for it. But here’s the thing. We who call ourselves disciples could argue it’s a pretty good bargain. As McGhee charts for us so well in her book, the other option hasn’t gotten us very far at all. “For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake, and for the sake of the gospel, will save it.” Amen. Notes: [i] McGhee, Heather. The Sum of Us (p. 38). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. [ii] Ibid. (p. 39). [iii] Ibid., (p. 40). See also Adam Nossiter, “Unearthing a Town Pool, and Not for Whites Only”, September 18, 2006 in NY Times. Retrieved on February 26, 2021 from: https://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/18/us/18pool.html?smid=url-share. [iv] Ibid. (p. 40). [v] Ibid. (p. 37-38). [vi] Ibid. (p. 7). [vii] Ibid. (p. 20).

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed