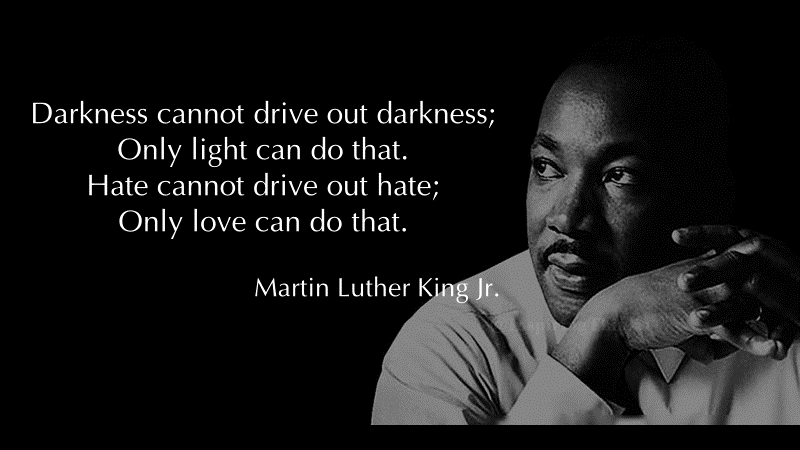

Scott AndersonI am an avid reader of the comics. If I’ve read nothing else from the paper on a Sunday morning I will look at breaking news to see what we need to be mindful of, and I will read the comics--religiously! Pearls Before Swine is one of my favorite comics these days, and I love how this one gets right to the heart of our stress-filled, bubbled, and too-often disconnected existence. And more to the point, I love how it gets to what is at the center of this gospel today: Love your enemies. Or maybe it doesn’t. To imagine the person who cut you off on the freeway is your enemy is something of a stretch, isn’t it? It’s a verbal weaponization of a pretty mundane event, to imagine my neighbor on the freeway is my enemy, and not instead, someone who may be having a bad day, like I might be. We probably shouldn’t domesticate the notion so carelessly, because there is much, much worse that is done for which we should preserve such a decisive word like enemy. In these days of Fake News, we should try to be as accurate and truthful as we possibly can. There is real abuse—abuse of people through sexual and physical violence, through manipulation and the misuse of power for personal or political gain. There’s what people do to one another in war, and through horrific programs of genocide. There’s the systematic dehumanization of people based on particular notions of sexual and cultural identity. There’s the systematic practice of extraction that takes from the poor and gives to the rich. There’s the particularly egregious abuse of the most vulnerable that happens in the name of God by our religious institutions. And we will not have to wait long at all to look back on this season of human history to recognize what an enemy we have been not only to our environment—to the plants and animals, the sea and the land—but to ourselves and our own survival in the process, through our disregard for our impact on climate and creation. There are more than enough appropriate uses for the word enemy. I suspect, then, that we should be careful not to overuse it and rob it of its meaning and impact. Which, of course, makes this text not less, but more difficult: Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you.[i] This is a hard word. It is a big ask that we need to explore. But first of all, let’s name what this is not. I think over the years we have learned enough about the nature of abuse to recognize that to turn the other cheek is not to suggest in any shape or form that a victim of abuse is obligated to continue in that abuse out of some twisted notion of loyalty or, worse, discipleship. We are, I trust, almost to that point where this caution is no longer necessary. But not yet. So let’s seek to be clear about this. Abuse in any form is never justified, and always to be resisted, especially on behalf of the most vulnerable. We need only to remember the text from last week in which, in just a breath or two earlier, Jesus gives a warning to those of us who rest in our privilege—of any form. He sides clearly with the poor and the vulnerable and with the God who also is a partisan when it comes to these matters. Blessed are the poor. Woe to we who are rich. What we have here is a continuation of a text that demonstrates the very practical and material realities of the Reign of God. And if Jesus’ words here are directed to anyone in particular, it is to those of us who are well resourced: Love your enemies. Do good and lend, without expecting to be paid back. Did you catch that? Then you’ll be like the Most High God who is kind not just to the vulnerable and the grateful, but to the ungrateful and the wicked, and even to that guy who cut you off this week. Be merciful, like God is. And herein lies the key. Here is one of the great insights of Jesus and the tradition and the leaders who taught him and those who have followed his way over the years. God’s powerful weapons to destroy strongholds and turn back evil are goodness, kindness, and generosity. God’s greatest weapon is love. This is one of the most stunning and powerful and counter-cultural insights of this gospel of ours. Turning the other cheek does not mean submitting to endless abuse, as we have already remembered. It also does not mean weak acquiescence, but the overthrowing of evil by the force of its own momentum. Turning the other cheek is about exposing evil intent for what it is. Turning the other cheek is about exposing the ultimate end of the tactics of entitlement, and exclusion, and extraction and violence. In his book Debt: The First 5000 Years, David Graeber, traces the way debt has for a long time been an important tool of the powerful against the vulnerable. A sustained and persistent process of the quantification of value, has long been supported by a readiness to enact violence against the vulnerable. Debt, in other words, has served for thousands of years as a tool of social control, as a means of assuring cheap labor, and as a reinforcement of social class status.[ii] And the fight is not a fair fight. So when he says lend without expectation of return, when he says forgive people their debts, Jesus is here suggesting a form of procreative, life-giving, asymmetrical warfare. Returning violence, not with violence, but with kindness. Returning greed not with greed, but with generosity. Returning hatred, not with hate, but with love. Resisting systemic practices that subversively trap people in poverty with overt practices that set them free. Finding, within the human spirit and within authentic communities, the strength to give ourselves for the sake of others. It is a tricky thing to talk of God’s mercy. Much of what we might count as mercy may, in fact, be privilege. I may not have to deal with trouble not because God is merciful, but because I’m a white, educated male. I may get off with a warning for speeding not because God is merciful, but because I am part of a privileged class that is more often given a pass. I may be more well-regarded than, say, a woman in the same role, not because I’m more gifted, but because I look the part, according to a tradition biased against women. When Jesus asks his listeners, “When you love someone who loves you, what credit is that to you?” the most interesting part of the question might be why credit is important? Why are we looking for credit anyway? One 20th century theologian observed that humans pray for mercy for themselves and justice for everyone else. What does this need for credit represent, and is it true? What tendency is in us to look for boxes that we can check off? To justify, to prove ourselves? To establish our goodness, as opposed to others? This, it seems, is an essential part of the sickness unto death that keeps us in conflict, the system of human oppression that not only affects the vulnerable, but the privileged. Jesus understands that these systems he names are evil in that they ultimately benefit no one in the long run. Every human life is misshaped and broken in the face of such inequality and cruelty. Creation in all its aspects is compromised.

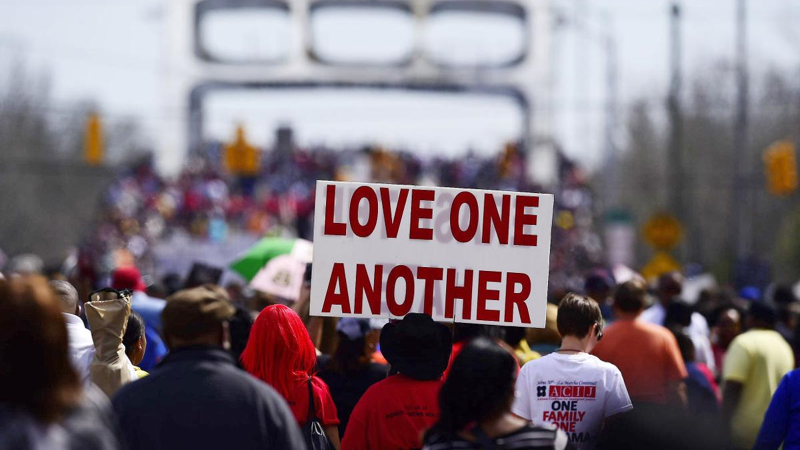

But this is not the last word. Our future is found in the courageous practice of this asymmetrical warfare we know as love—in all its specific and material ways. So in the place of entitlement, we seek neighborliness. In the place of exclusion, we practice inclusion. In the place of extraction, we seek the common good. In the place of violence, we advocate for justice and compassion. [iii] And it will be given to you. A good measure, pressed down, shaken together, running over, will be put into your lap; for the measure you give will be the measure you get back.[iv] Thanks be to God. Notes: [i] Luke 6:27-28. [ii] David Graeber, Debt: The First 5,000 Years (New York: Melville House, 2011, pp. 8, 82, 390-91). Referenced in Walter Brueggemann’s Tenacious Solidarity. Fortress Press. Kindle Edition (Location 960). [iii] Brueggemann, Walter. Tenacious Solidarity. Fortress Press. Kindle Edition (Location 3183). [iv] Luke 6:38.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed