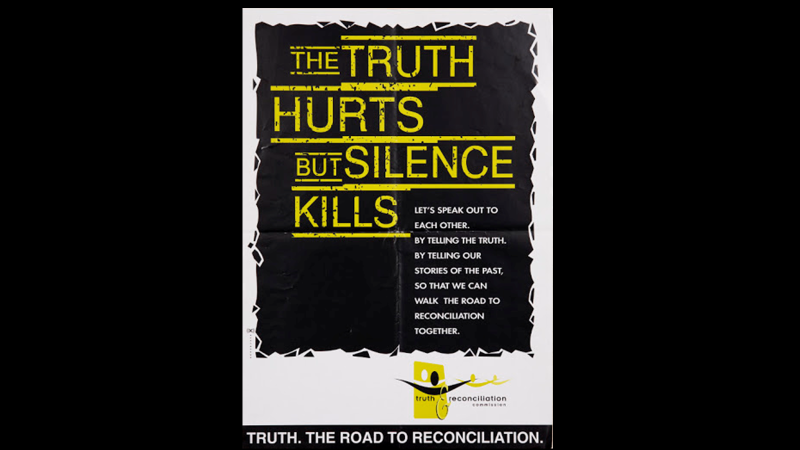

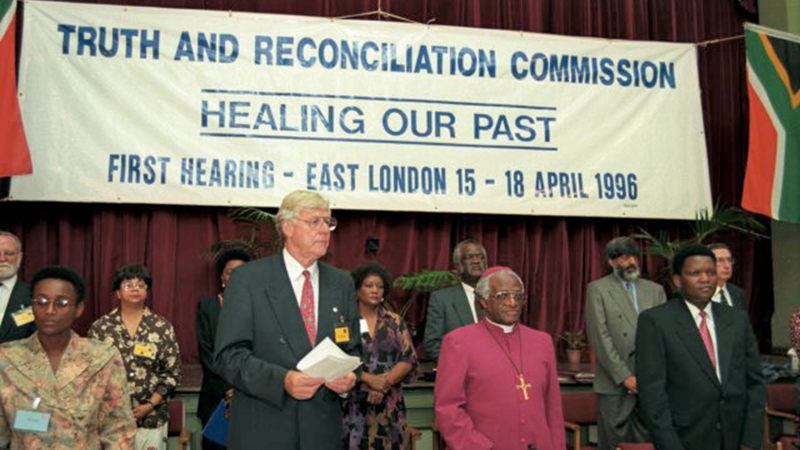

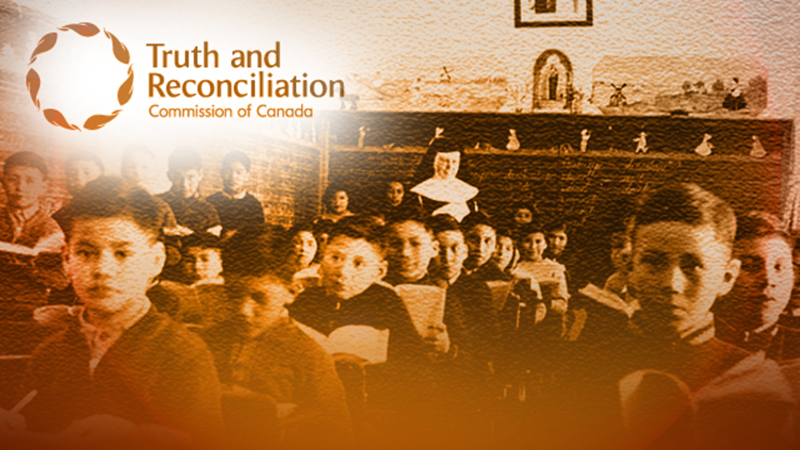

Maggie BreenIsaiah 58:1-9a † Psalm 112: 1-9 † 1 Corinthians 2:1-12 † Matthew 5:13-20 Choosing life is a painful business. Choosing life, means, choosing to take a look at the things that cause us pain. Choosing life for ourselves, and for others, means coming to terms with the things we have experienced; it means making peace somehow, with the ways we have been hurt, and the hurt we have caused. Not to overlook it, not to give up the call for justice and the need to set things right, when this is needed, but rather to engage in reconciliation – a clear eyed compassionate look - because if we don’t, if we choose to let our pain operate under the surface then we are in great danger of passing that pain on in all sorts of, often unintentional, yet nonetheless, creative and death dealing ways. Piece of cake, right? I can understand if this passage about reconciling our past wrongs leaves you feeling a little inadequate or less than inspired, because we all know, in our guts, if nowhere else, that reconciliation is hard, often excruciating work. It’s not, for the most part, a quick trot over to an offended party, an apology, a hug, and then back to the altar. Reconciliation is hard because it means looking at the truth. Looking – with as much self-awareness as we can bear (to quote Julie Kae) – at the truth of the hurt and the pain we carry around with us – pain that comes from our mistakes and the losses that come with them. Such truth-telling, such self-awareness, is nothing less than the work of a lifetime; my life and the life of those I touch depend upon ongoing acknowledgement and ever deepening compassion for the pain I carry around, and for the truths that will always in some fashion be a part of me. Now, while the rest of this passage from Matthew may not sound reassuring, there is, in fact, some good news contained in it. You have heard it said, ‘You shall not murder’; and ‘whoever murders shall be liable to judgment.’ 22But I say to you that if you are angry with a brother or sister, you will be liable to judgment. Now tell me - who on God’s good earth has never been angry? And if you insult a brother or sister, you will be liable to the council; and if you say, ‘You fool,’ you will be liable to the hell of fire. Honestly, who in heaven or on earth has never muttered an insult under their breath on in their hearts, “You have heard it was said, ‘you shall not commit adultery.’ 28But I say to you that everyone who looks at another with lust has already committed adultery with them in their heart. Hmm enough said – it’s not just the doing. Turns out even thinking about it is a serious offense. “It was also said, ‘Whoever divorces his wife, let him give her a certificate of divorce.’ 32But I say to you that anyone who divorces his wife, except on the ground of unchastity, causes her to commit adultery.” Now this one has caused much ink to be spilled as we point out the sins of others, but these words are not about divorce in and of itself, so much as they are about those with power using this power without compunction to get them what they want, just because they can. And there are too many ways to count in which those of us with power do this self-same thing. I know if doesn’t sound reassuring. But what I want you to hear from this text as we think about entering the work of reconciliation is that, if there is a line to be drawn between right and wrong, we are all on the wrong side of it. None of us is better than the next person. Absolutely, some things have more serious implications than others, but no-one, not anyone, escapes the need for the work of reconciliation, we all fall short and there is pain in the falling, but Jesus wants to let us know that we can let go of the idea that we are somehow meant to get it right in order to be acceptable. That is impossible and it’s powerful and harmful lie. If we buy into the idea, even subconsciously, that we somehow need to be perfect, that it is somehow possible to get ourselves over that line then our grip gets tight and anxious and we find ourselves, lashing out or scapegoating or despairing and just generally having a hell of a time. If on the other hand, we can loosen our grip on the belief that we can somehow measure up. Should we accept that God accepts us just as we are, well from here a peace that lasts becomes possible. This is, of course, not to say that pain doesn’t matter and that we shouldn’t hope to do well by each other. Of course, we should. But things will happen, we will make mistakes, we will hurt and get hurt, and when they do, if we can let go of imagining that we have crossed over, away from God’s good grace then we might be able to relax into a greater gentleness with ourselves as we make our way; we might see more clearly that we are not alone in carrying pain; and from this place of understanding and reconciliation with ourselves and who we are before God, the reaching out to others in peace and curiosity and love and compassion gets easier and more full of possibility. There have been calls for the US as a nation to engage in a “truth a reconciliation” process around the massive pains of Native American genocide and slavery and other serious injustices towards group of marginalized people. These calls are based in the understanding that until we face our past in intentional way we will continue in unjust patterns of oppression. Truth and reconciliation processes have been in play on the world stage since the mid-1970s. They began in countries within the continents of Africa and Central and South America as countries there emerged from the horrors of tortuous regimes. These processes have developed over the years with the most well-known taking place in South Africa between 1995 and 2003. At the end of apartheid. More recently processes have happened in North America: in Canada, between 2008 and 2015, to look at the impact of residential schools on indigenous students and their families; in Greensboro, North Carolina, between 2004 and 2006, 25 years after the Greensboro massacre in which 5 anti-clan protestors were killed, and in Maine between 2015 and 2018 as it tried to reconcile with abuses towards native children that occurred in its child welfare system. Truth and reconciliation processes take a restorative and not a retributive approach to justice. And they are anything but easy. Truth and reconciliation processes operate out of the belief that confronting and reckoning with the past is necessary for successful transitions from conflict, resentment and tension to peace and connectedness. According to the Greensboro commission “There comes a time in the life of every community when it must look humbly and seriously into its past in order to provide the best possible foundation for moving into a future based on healing and hope.” Many of the commissions that have taken place have spent years listening to victims and perpetrators, as well as to any community members who need to report their experience of the injustice in question. The process takes the truth of those injured seriously – gives this truth time and space – makes sure it is recorded and acknowledged. And then once all have been heard, the commission decides upon the steps that must be taken to make things right and to help all sides enter a process of forgiveness and healing. Many of these processes have been criticized because there is no enforcement mechanism and parties have often stopped short of implementing the recommended actions. At the same time just looking at, naming and acknowledging the truth of the injustices has been held up as healing and restorative. A witness in the South African process names this: "To me, the most important part of the truth commission was not the report, it was the seeing on television of the tears, the laments, the stories, the acknowledgements.” And, as one political scientist there put it, what the truth commission did was powerfully “convert knowledge into acknowledgment.” Reconciliation does not come without truth, and it is this step towards facing the truth of who we are that Jesus assures us we are safe to take. Its a step towards naming, acknowledging and reconciling ourselves to the truth of who we are. It takes time and deep compassionate restorative listening. Listening to ourselves and others we trust as they help us find language for what we know to be true. And truly we can let go of the idea that its possible to not be good enough. You are good enough. Truly we can hold on to the promise that we, with everything we carry, with all that we are, all that we have are have done or not done, we are forgiven, loved and claimed by God. We are as worthy of God’s love and promise as any other. No better. No worse. No difference. And truly in our acknowledging our common pain and our common acceptance before God, we are better equipped to reach out, To reach out with kindness, with compassion and humility and understanding. This is our work. To choose life. With joy and faith, as hard as it is, one step at a time, over time, looking at the truth of who we are, looking at the pain of life and the love God offers us with as much self-awareness as we can bear. From here with God and in the company of each other and all the saints we will have the foundation we need to give ourselves fully to the ways of peace. Real peace. May the peace and deep love of God be with you.

Amen

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed