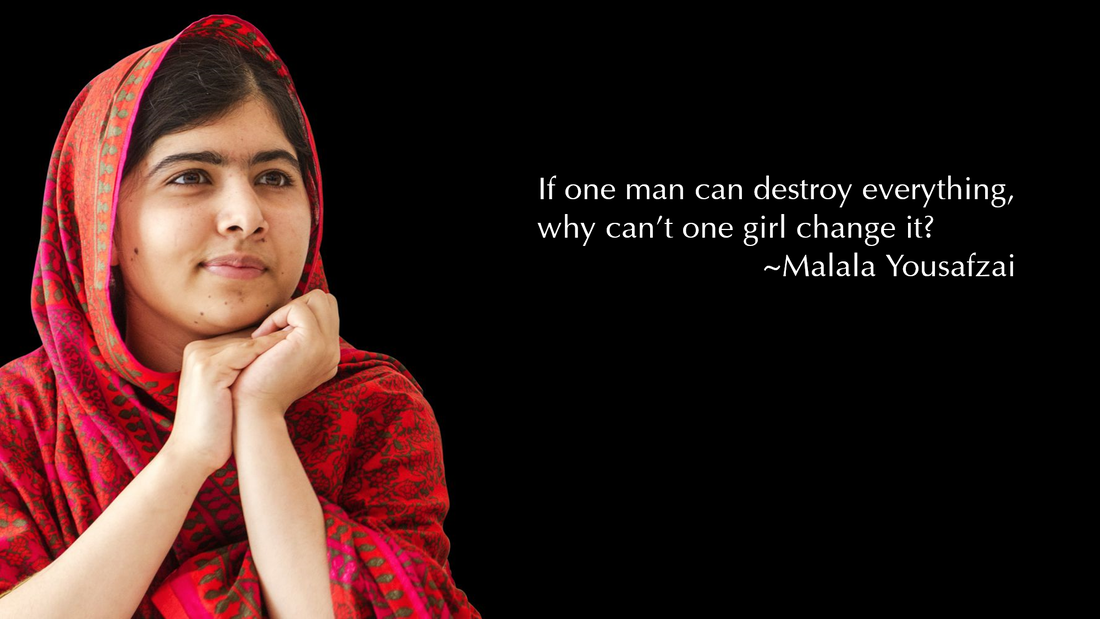

Scott AndersonDaniel 12:1-3 † Psalm 16 † Hebrews 10:11-25 † Mark 1:8 “’Hope’ is the thing with feathers,” says the 19th century poet Emily Dickinson.[i] “Hope” is the thing with feathers - That perches in the soul - And sings the tune without the words - And never stops - at all – Hope is feather-light, the smallest and most vulnerable of things, yet it has such potential to evoke possibility against unimaginable odds. Dickinson’s embodiment of hope seems a little jarring juxtaposed to the principalities and powers that show up in Daniel and Mark today. Such solidity and heft against such a fragile thing—teacher, “what large stones and what large buildings!” You get the sense anything so insignificant would be crushed in an instant, would be powerless against such size and force. But Dickinson isn’t done. In fact, she ups the ante, throwing this feathered creature into the tempest. And sweetest - in the Gale - is heard - And sore must be the storm - That could abash the little Bird That kept so many warm – Feather light, untamed, unselfconscious, pushed and pulled by the winds but not battered—as if it is the wind itself. Hope refuses to be humbled. It does not despair. Simply, it is beyond our control, a thing in flight that causes us to soar. True hope is not a thing we possess. It possesses us. It intrudes on us, claims and directs us. I’ve heard it in the chillest land - And on the strangest Sea - Yet - never - in Extremity, It asked a crumb - of me. Hope alights on these passages from both Daniel and Mark. Jesus sees this, even if the disciples don’t. Both of these texts are so-called apocalyptic literature. We will get our fill of these over the next month or so—which is important, I suspect, if for no other reason, because the sound of them is so foreign to our modern, self-sufficient ears. Apocalypse simply means to “uncover.” It is less about fanciful future prophecies and more about revealing what is true in a time of fake news. This is important to understand because there has been a strong, visible tradition in American Christianity that has taken to reading these stories like a crystal ball. Apocalyptic literature, the likes of which we encounter today, does not as much predict future events as it uncovers what in the world is going on in the here and now and where God might be in the midst of it all—huddled, let’s say, with his followers, sizing up what’s what and reminding them what truly sings. So let me say it again, Daniel, for example, or the book of Revelation, or even Mark’s Jesus are not looking across the eons to a single series of cataclysmic events; they are paying attention to their current day. And so these biblical texts seek to open our eyes and ears to God’s saving work and sublime beauty—here and now. They demolish what we imagine to be reliable, so we rely once again on what cannot be demolished—like hope, like resurrection and the irrepressible newness of life. Do you see these stones? Don’t count on them for the long term. There is stronger stuff, Jesus says. There is life that is stronger than any death. But these stones and their destruction reveal something important. Do you see it? Truth is exposed in the same way, we might venture, as a series of wildfires: Do you see these fires? Prepare for more deadly weather patterns including longer droughts, higher temperatures and even more devastating disasters. There is danger her. Wake up to it. Live and learn. Do you see this bear? Her kind will face more and more difficult odds as her habitat and her food sources continue to diminish? Do you think you are somehow disconnected from her? Do you see this child? This is 7-year old Amal, who became a symbol of the devastation of the war pitting Houthi rebels against a Saudi-led coalition. The Saudi campaign of airstrikes—aided by American bombs and intelligence, we should note—have killed thousands of civilians. And the economic warfare that has been waged alongside the bombs has worsened the despair of many Yemini families and cut off the supply of food. The conflict began three years ago. But it didn’t catch our attention until the killing of Jamal Khashoggi shined a spotlight on Saudi actions in the region. Do you see what’s going on? The little girl, Amal, died at the beginning of November at a refugee camp four miles from a hospital. The United Nations warns that the number of Yemenis relying on emergency rations could soon rise to 14 million—that’s half of Yemen’s population.[ii] Do you see these stones? Do you see them? Do you see orca J35? Do you see Tahlequah, this mother in mourning, carrying her dead calf for seventeen days? Do you see her as she somehow, knowingly shows the world her grief so we might learn? Are you surprised by these things? Don’t be. There will be wars and rumors of wars. There will be signs in the heavens and on the seas; there will be famines. Learn from them. Learn from this destruction the empathy and love and alarm we need. You see, to hope is to believe that a better response is possible. To hope is to see the life that comes to you and me. Apocalyptic literature is born out of crisis, and that is precisely what we have in Daniel, whose community is wrestling with how to respond to unhinged events in their own time. Apocalyptic writing is the result of collapsed buildings and thousand-year floods and wildfires and shrinking ice caps and fake news. And it warns against the idols that will vie for your trust and lead you down empty paths: “Many will come in my name,” Jesus says. Preacher Thomas Currie says of all the tasks to which the church is called to undertake, the one that makes the least obvious sense is to hope. Politics and wealth are perhaps the most obvious idols that replace true hope. To those he adds loneliness—the “quiet despair that pervades our conversations and manners.” He says, “Our loneliness has taught us a kind of comfortable hopelessness that narrows our vision and settles for less than the fullness that the hope of the gospel intends.”[iii] “That is the thing about hope:” he says, "it is not something we “have” so much as it is something that intrudes upon us, even claims and directs us. We hope because Jesus Christ was raised from the dead. That…is the source and substance of all hope. And we had nothing to do with that."[iv] Our hope is dependent on the one who overcame death and continues to do so, to breathe in the Spirit who breathes life into rattling bones and, sifts through the rubble of collapsed institutions to show us what is true and lasting. Like Dickinson’s bird, true hope comes to us. It is not in our control. But come, it does. Hope these days, I think, is embodied in the irrepressible nature of humanity that continues, even and especially when things are at their worst, to give themselves to the better. Is that anything but a witness to Jesus Christ raised from the dead? Hope is what comes once we see through the plays of power and control that seek individual gain at the expense of many. Hope is what comes when we find within ourselves more strength and durability and grit than we ever imagined was possible. Hope happens in our politics, among other places, but our hope is not in politics. It is seen in generosity, but our hope is not in wealth. It is found when we remember that we are not alone, but our hope is not in community. It is in the resurrection and the life that is made known even in death and destruction. It is the irrepressible spirit that lives in you and me that takes flight, sometimes only once the destruction has cleared a path for it. But soar it will, for these are the beginnings of the birth pangs, but new life is coming. Thanks be to God. Notes:

[i] Emily Dickinson, “’Hope’ is the Thing with Feathers” from The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson, ed. Thomas H. Johnson (Belknap Press, 1983). Retrieved November 16, 2018 from https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/42889/hope-is-the-thing-with-feathers-314. [i] Declan Walsh. “Yemen Girl Who Turned World’s Eyes to Famine Is Dead” in the New York Times, November 1, 2018. Retrieved on November 17, 2018 from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/01/world/middleeast/yemen-starvation-amal-hussain.html. [iii] Thomas W. Currie. “With Head Held High: Preaching Hope in a Noisy Time” in Journal for Preachers, Advent, 2018, p. 4. [iv] Thomas W. Currie. “With Head Held High: Preaching Hope in a Noisy Time” in Journal for Preachers, Advent, 2018, p. 3.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed