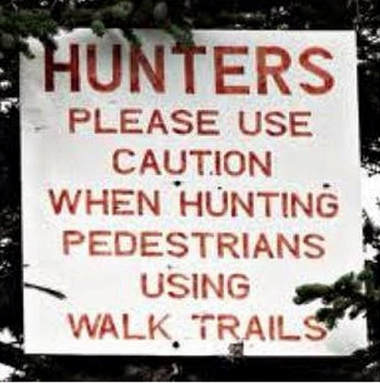

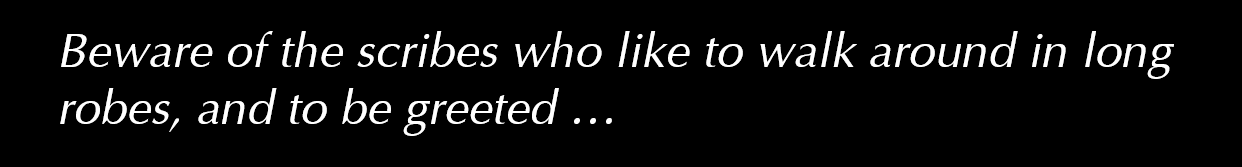

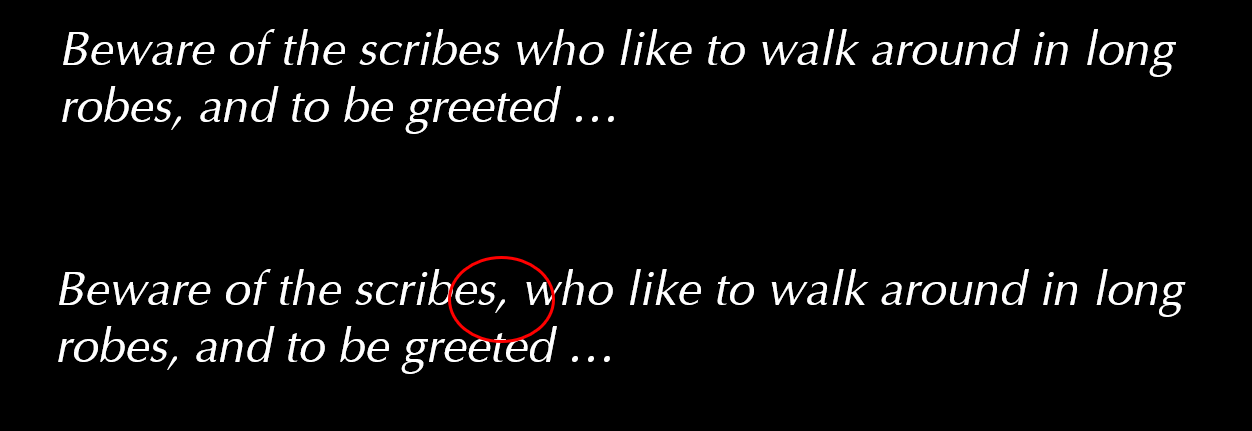

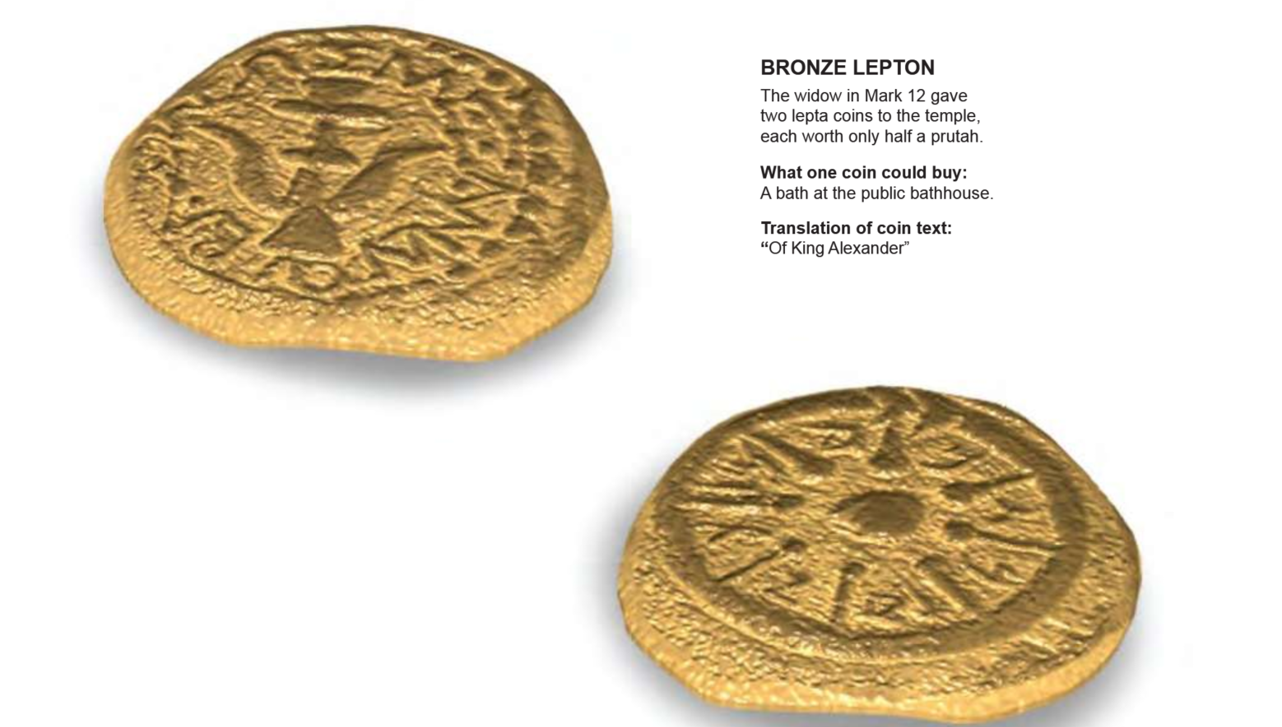

Scott Anderson1 Kings 17:8-16 † Psalm 146 † Hebrews 9:24-28 † Mark 12:38-44 Beware the comma! It can change everything. It can be a matter of life or death. It can be the difference between “Let’s eat, grandma,” and “Let’s eat grandma.” Or consider another sign I saw not too long ago:  “Hunters, please use caution when hunting pedestrians on the trails” …which could have benefitted from a comma so that it would suggest that one should be aware of the presence of others while hunting. Now when it comes to our ancient biblical texts, there is an added problem. As you may know, the original texts of both the old and new testaments didn’t have commas, or really, any punctuation at all! They were a bunch of words jammed together, that really only gained their meaning as people read the letters out loud and formed them into words. That’s part of what is behind the story of the Ethiopian Eunuch who meets Phillip in the book of Acts.[i] As language developed and real-estate on the page became more abundant, punctuation developed to help us clarify things. But that wasn’t always the case, and the challenges it presents can still haunt us as choices are made as to the meaning we give to particular stories. Take as a case in point, Jesus’ warning today about the scribe: “Beware of the scribes, who like to walk around in long robes, and to be greeted with respect in the marketplaces, and to have the best seats in the synagogues and places of honor at banquets![ii] Sometimes it takes more effort not to notice some people: Beware the scribes, he teaches his disciples. They walk around in impressive clothes and are always working to get a shout-out in public. They score court-side seats at the game and make sure they have rooms named after them at church to advertise their generosity and goodness. We know the type; we know the need for attention and self-promotion at any expense, including the expense of others. Mark is ruthless—he caricatures the scribe as one who at every stage of social life wants privilege and status and power. Of course, these attitudes are exactly opposite to Jesus’ nonstop instructions to his own community. If you want to be my disciple, you will be last, and servant of all. And some in the Mark narrative are beginning to get it, including some we might not expect. I read the text like it is punctuated in your Bibles, but, here’s another take on it: Beware the scribes who like to walk around in long robes, and to be greeted with respect in the marketplaces,” and so on. There’s a difference, isn’t there? Is this a statement about all the scribes, as if they were a monolithic class of predatory narcissists? Were all scribes cruel bullies who were only concerned about themselves? Unfortunately, such generalizations have been used through history to act against whole groups of people and to perpetuate cycles of violence that seem to have no end. You or I might have thought this was a thing of the past—a relic of ancient fears—but recent events suggest differently. In fact, according to a recent study, hate crimes in our largest cities have increased each of the last four years, and that’s against a backdrop of declining crime rates overall.[iii] And besides, if that were the case, how do we square what happens just a few verses earlier in Mark when another scribe responds positively to Jesus and Jesus looks at him and says, “You are not far from the kingdom of God”?[iv] You see, sometimes, the type is movable. Sometimes you need to give the sentence and the story it tells about people you may have already decided on a second look. I’ve been trying to do that with the story of Elijah and the widow at Zarephath. Perhaps it isn’t a problem with a comma, per se, in this story, but if you look closely, the story does start out pretty dicey. Here you have this poor widow. She woke up this morning bone hungry, at the edge of famine. She is at her end. Her last bit of flour. Ready to bake one last meagre loaf of bread for her child and herself before death brings perhaps the first comfort in a long time. We know people like this. And in comes this prophet—a foreigner demanding the hospitality her culture demands of her. Set aside your own needs, and your son’s, for this outsider and his promise. Here you have this poor widow who has nothing, and Elijah comes to her and demands courtside seats. And even worse, God sends him to do so. You can feed yourself and your son in a minute. Feed me first. Give me something to drink, first. Serve me, first. Throw those last two coins in the treasury and everything will go well with you. You get the sense that the story could have ended a lot differently, don’t you? What if he had been more like the scribes who were more interested in devouring a widow’s house than communing in it? Which would it be? “Let’s eat widows” or “Let’s eat, widows.” How would she know where the story would place the comma? It just feels wrong that these widows who have nothing should be asked to give everything. And that certainly seems to be where Jesus places his comma as he takes a seat courtside and watches people give at the temple treasury. And while this seems to work out pretty well for the mother and son in Zarephath, you don’t get the sense that the widow who has given her last two coins and her whole life is any better off in the short term. There is this consistent claim, this persistent belief in our Christian story that blessing comes when you embrace someone you aren’t supposed to, when you give of yourself in ways that go against your best interests, that take a chance. When you put yourself and your wants second. But there’s also a clear sense that widows get taken advantage of, regularly. There are systems that are so ravenous that they have no limits when it comes to what and who they will devour. It doesn’t really add up, does it? And the more we do the math, the more troubling it gets. You see, while Jesus sits and watches, he does a little math of his own. The woman puts in two small copper coins. The story says they are worth a penny, but that may be inflating it a bit. It probably took about eight of these coins to add up to a penny, so she’s closer to a quarter cent. If you round it, it becomes no thing at all. It will disappear as this woman would have, had not Jesus paid attention. It will disappear as so many of our unhoused neighbors do every night into their cars or under bridges along I-5 and the Cedar River. Yet, Jesus declares that she has given more than anyone else. How could this be?

Part of the answer is in statistics and percentages. They have given out of their abundance. We have much left over. After our offering, we’ve still got a balance in the bank account to buy the groceries and pay the heating bill and do the electronic funds transfer for the lease on the all-wheel-drive chariot with heated seats, navigation, and advanced safety features. But not this woman. She has given all she has. All of it. And it matters that she has two coins. Even though they are worth next to nothing, she has two of them. She could have held one back. She could have given one and kept one in her pocket maybe for a slice of bread for dinner for her and her son, but she didn’t. The Greek makes it even clearer; literally, she gives everything; she gives her whole life. In her silence the widow seems to embody the very kind of faith that many only pretend to live by. And Jesus sees it and points it out for all of us through history who would be disciples. Here is a witness to the gospel of Jesus Christ: this woman who has nothing and has given everything. Stop. Look at her. Listen and learn. So what are we to make of this? Our faith does not offer guarantees, does it? As much as we would love for it to peddle certainty, that’s just not where we live. We step out in faith, trusting in a self-giving, I’m-going-to-come-second Way and even more in a Presence and a Power and a Goodness that punctuates life with hope. And the hope isn’t that waves of goodness are going to come our way all the time. Perhaps not even most of the time. The hope is in a way of being and living that follows after the One who watches out for widow’s houses and praises scribes who were inclined to do the same. You see, while there is not a certainty to our faith, there is a clear and certain heart to it. And knowing that helps us to read between the lines even when the punctuation is lacking, to find our way and to hold onto the hope that is the exclamation point of these texts. It is hard to deny that Old and New Testament both are born out of poverty and displacement and speak good news into it and to the poor who find themselves trapped in cycles of suffering and death and to the outsiders who long for a home. And the brilliance of the gospel as I understand it is to see that through the speaking of good news to the least it speaks with a full-throated good news to everyone—precisely in the midst of uncertain times like these. When the least are better off, we all are. We come to know the ways of peace. We have the possibility of sharing a common and full life together that is inoculated from danger and instability. That we come to know a home only when we know it to be shared. That we know the fullness of life we crave when we choose to go second. Our hope has always been the hope of widows and orphans and immigrants and homeless. That’s why Jesus sits and watches her so intently as she offers her last two coins, and says to us across the ages, look at her, and learn. The Reign of God belongs to her. If you want to know it, if you want to know me, know her. How I come to her is how I come to you. Amen. Notes: [i] Acts 8:26-40. [ii] Mark 12:38-39. [iii] See Abigail Hauslohner, “Hate crimes jump for fourth straight year in largest U.S. cities, study shows”. Published May 11, 2018 in The Washington Post. Retrieved on November 9, 2018 from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2018/05/11/hate-crime-rates-are-still-on-the-rise/?utm_term=.06fa95e15e96. [iv] Mark 12:34.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed