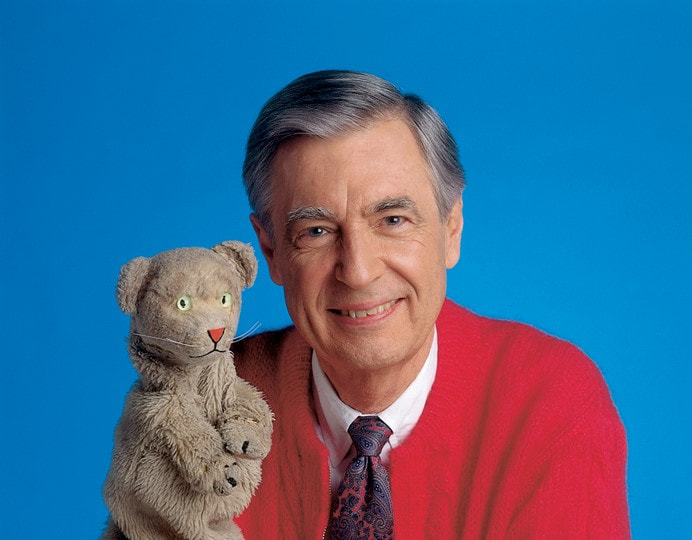

Scott AndersonFred Rogers first encountered a television in 1951 when he was a senior at Rollins College. He hated it. People were throwing pies at each other, doing goofy things. “Why is it being used in this way?” he wondered, when it could be such a “wonderful tool for education.”[i] He was so struck by its potential that he told his parents he wanted to delay his plans to become a Presbyterian minister in order to pursue a career in television. And so he did. In 1966—the year I was born—he created “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” on Pittsburgh public television. In 1968 it began a run of more than three decades on national public television. And it raised my generation and many after me. It’s slow-paced, gentle approach eventually led the show to be outflanked by the manic movements of Sponge Bob Square pants—which we loved as parents—pie-throwing included, and the psychedelics of Adventure Time, among many others. I don’t think my 20-something kids were much influenced by Mr. Rogers, but I certainly was, and I’m frequently overtaken by nostalgia for him and what he represents. But I don’t think its just nostalgia. My emotion—seriously, I can’t read or watch much about him before that lump starts to grow in my throat and my eyes start to sting—perhaps you share that. The emotion is there for me because of what he did and what he represents. Rogers built his show around themes of kindness, civility, and empathy, and through thirty years of programming, he and his show never lost sight of those core values. And as important as these themes are, especially in today’s climate, it was his consistency, and the way he seemed to never lose that sense of what it is like to be a child, that really gets me. He was and is a model of integrity and principle through fifty years of profound change. In an age when public kindness is scarce, he was a force for radical, principled generosity. Here’s an example or two: During the civil rights era, when black kids were being thrown out of swimming pools, Rogers and a repeating character on the show who was black bathed their feet together in a tub. After Bobby Kennedy was killed, Rogers gently explained what an assassination was. In 1981, Rogers devoted a week of programs to the topic of divorce. Initially, he resisted, but his staff convinced him that parental separations had become so common that kids needed help in figuring out how to deal with it. In this clip from one of those episodes, Mr. McFeely, has been reflecting on his 45 years of marriage when Mr. Rogers brings up the topic of divorce.[ii] Mirroring the anxiety of society at the time, Mr. McFeely is obviously uncomfortable, which sets the stage for the discussion that follows. Morgan Neville, the Academy Award-winning filmmaker whose documentary “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?”[iii] is now available on video says that as he began his research for the film, he discovered in Rogers, a “revelation”: “I was hearing a voice I felt I wasn’t hearing anymore,” he said. “It was a grown-up voice, someone who was looking at the long-term well-being of ourselves and our neighborhood.”[iv]

It was also a voice that had the ability to do something that I, for one, find so difficult to do—to take out the complexity of an issue without dumbing it down. “Life is deep and simple,” Rogers often said, “and what our society gives us is shallow and complicated.”[v] I suspect there may be something here for us that links deeply and simply to the texts for today as Jesus responds to the confusion and the ambitions of his followers by drawing a child near. A dear friend, one of the most gifted and loving pastors I know, shared a story of a recent experience at his church. He walked into the men’s bathroom and was taken aback to see a woman there. He offered a “hello” but his surprise was evident. It turns out an advocacy, support group that meets in his church building was on-site, and the person in question was a transgender man. Now, my friend, as I said, is not naive. He is also a gay man and married to a loving husband. He knows the territory, and he knows what it’s like to be vulnerable, and yet, even he found himself momentarily surprised, and regretting his reaction. How much more dizzying it might be for those of us who try to navigate these times when so much is shifting so rapidly. Even with the best of intentions, we don’t always keep up and we don’t always respond as we wish—we may feel childish, vulnerable as we try to navigate this brave new world. In a way, it was this sense of vulnerability we all share to one degree or another that Fred Rogers sought to speak to through the camera. There’s a clip that opens the documentary in which Rogers is trying to explain his sense of the work he is up to. He was an accomplished piano player and composer, so he’s at the piano, and he’s referring to the idea of modulating from one cord to another. “It seems to me,” he says, looking at the camera, “that there are different themes in life. And one of my main jobs is to help children through some of the difficult modulations of life.”[vi] He tries to explain further: It’s easy to go from C to F, but other modulations—like from F to F# you’ve got to weave through all sorts of things. Our ability to make our way through life comes from our connection to that which is simple and deep, that which never leaves us, those values of love that extend not just to our neighbors of all sorts, but deep within ourselves as we remember our value and holiness. “A harvest of righteousness is sown in peace,” says James, “for those who make peace.”[vii] And so Jesus looked to a child—a little one, an invisible one whose vulnerability is so present, whose authentic self has not been buried by external expectations or pressures to be what you are not. “Whoever welcomes one such child in my name welcomes me, and whoever welcomes me welcomes not me but the one who sent me.” If we take the kind of quiet moment Mr. Rogers often gave his audience, we may begin to realize what a powerful and radical and promising thing this is. There is deep within us the potential to welcome God into the fray as we welcome the child within us and within the other. Mr. Rogers said, “I don’t think anyone can grow unless they are accepted exactly as they are.” Fred Rogers is such a profound and lasting and emotional symbol for me because his life speaks to the power of goodness that is so often found in the immediacy of these children Jesus tells his disciples is the model for welcoming God. He reminds us that this is how people can be. He reminds us of the way the world can be. A director once said of the show, “you take all of the elements that make good television and do the exact opposite. You have Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood: low production values, simple set, unlikely star. Yet, it worked.” It still can—not a nostalgia for something long past, but this way of love, this kindness, this child in you. Thanks be to God. Notes: [i] See “’Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood’ at 50: 5 Memorable Moments.” New York Times, March 5, 2018. Retrieved on September 21, 2018 from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/05/arts/television/mister-rogers-neighborhood-at-50.html. [ii] Retrieved on September 21, 2018 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=48&v=p8bJ-2ScpnM. [iii] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt7681902/. [iv] Robert Ito. “Fred Rogers’s Life in 5 Artifacts” New York Times, June 5, 2018. Retrieved on September 21, 2018 from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/05/movies/mister-rogers-wont-you-be-my-neighbor.html. [v] See, for example “Mister Rogers & Me” from KPBS, Retrieved on September 21, 2018 from https://www.kpbs.org/news/2014/mar/14/mister-rogers-me/ and the Goodreads website https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/1151810-life-is-deep-and-simple-and-what-our-society-gives. [vi] Fred Rogers says this at the piano, using key modulation as a metaphor in the first scene of “Won’t You Be My Neighbor.” [vii] James 3:18.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed