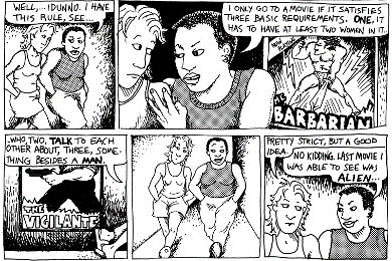

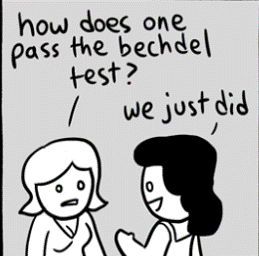

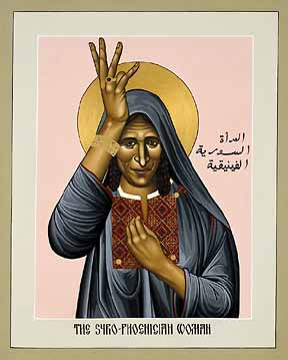

Maggie BreenJob 38:1-11 † Psalm 107:1-3, 23-32 † 2 Corinthians 6:1-13 † Mark 4:35-41 My Kids and I were watching Iron Man 3 on Friday night. We are working our way through Marvel movies – escaping the news, looking for the good guy, enjoying the quick wit. We were laying on various couches when the scene turned to Pepper Potts, the hero’s very capable assistant and now girlfriend. She was driving a car, fleeing a dangerous scene, with another woman Maya Hansen in the passenger seat. Maya is a brilliant scientist and previous acquaintance of the aforementioned hero – Mr. Stark. One woman turns to the other and they talk very briefly about the work in which the woman scientist is engaged Molly pointed from her couch and gasped – oh, I think this means this movie passes the feminist movie test. Wait, what? There is a feminist movie test? Yes, she explained there is this test used to rate movies. You ask of a movie – does it have two women in it, does they have names, and do they talk to each other about something other than their thoughts or their relationship with a man. In that one scene Iron Man 3 just scraped over the bar. This test it turns out is called the Bechdel test. It emerged from a comic strip written in 1985 by Alison Bechdel. She credits the idea to her friend Liz Wallace and to the writing of Virginia Wolf. Wolf in her 1929 essay, A Room of One’s Own, remarked that: “All these relationships between women, I thought rapidly recalling the splendid gallery of fictious women are too simple… and I tried to remember in any case in the course of my reading where two women are represented as friends. They are now and then mothers and daughters. But almost without exception they are shown in their relation to men. And how small a part of a woman's life is that.” Now this rule and others like it have been much debated and many would agree that they are nowhere near complex enough. But rules like it can be a useful place to start if you want to think about how we tell our stories and whose story is not being told. The point is not about meeting some quota, checking a box, giving a movie or other telling of tales a pass/fail. It’s about looking for and giving space to characters outside the norm – a the norm that is still very much white, male, cis-gendered, straight, young and able. It’s about being able to regularly be with their stories of real people. Stories that are complex, and rich, interesting, joyful, hard, relatable, and wonderful. The type of stories that move us to realizations of our deeply shared joys and concerns, even within all our diversity, and stories that perhaps challenge the powerful ideas we hold about of who our neighbors are and what they care really about. Many, in fact I want to say most, stories in the bible fail the Bechdel test. These stories of God moving in the world in ancient times were told in and through a time when women were not part of public life. One of my professors makes the argument though that the fact that any women show up and show up in the ways they do is really nothing short of miraculous and we should take notice. The Samaritan woman carrying the word of God to her people. The Syrophoenician woman changing Jesus’ mind and insisting that her family’s life matters too. The women at the tomb, and the women who preside and lead in the early church. These together with Jesus healing of the sick and challenges to authority turns a blind eye to suffering are all evidence that God is interested in including those whose stories we tend to hold at a distance. So it was interesting as I was thinking about the way we shape our stories and whose voices are there and whose are not that as I read today’s texts of a powerful God speaking to our fears and our confusion that I hear the voice of a mother. I have only ever heard a male voice before, but there she was to me this time A mother connected to world she has birthed in deep and powerful ways and one calling her charges back to the memory of who she is and what is expected of them. Job and his friends been through 37 chapters together before we get to today’s text and in these chapters they spend all of their time speculating and blaming and speaking for God on the topic of how Job could be in such trouble. They are telling a story of how the world works and trying to make Job’s experience fit. If you remember the story, Job had lost everything. All that he knew and relied upon. Everything. His livelihood, his family, his health. He is desperate, and his friend comes to tell him it must be his fault, to pray for divine assistance, to ask him to repent. They converse and they wrestle with the way what they see Job’s experience is bumping up against what they are sure they know about how to ensure one’s well-being and future prosperity. The good flourish, the wicked are stricken - simple as that. Job must have sinned. Repent and God will bless you again. Job insists that he has done no evil and spends significant time wrestling with how he can be where he now finds himself. He thinks about the presence of other evil in the world and where on earth God is in all of that. There are these haunting few verses in chapter 24… “There are those who snatch the orphan child from the breast, and take as a pledge the infant of the poor. …..and the throat of the wounded cries for help; yet God pays no attention to their prayer. How does this all add up he wants to know. A good man in trouble, unutterable pain in the world, and the treacherous so often apparently going scot-free. But then finally in the verses we have today God speaks. At first I hear the voice of my own mother admonishing me – who do you think you are?! But then I hear the expansiveness of this Godly parent’s claim. A cosmic mother bellowing into Job’s heart and into mine. Look at what has come from me. The very foundations of the earth. The seas that burst forth from the womb, the clouds that I made as its garments and the night as swaddling bands. These things I put in their place and showed them their limits. The rhythms of the earth, her voice goes on, and the vastness of the universe, and you, your very being alongside all of it. You think you can know? You think you can measure, put into a neat equation all experience and make it all add up? Its complex and wild and rich and beautiful and it’s under my care. It’s not an entirely satisfactory answer the why question is still there, but I do think the voice of this mothering God constructively moves us away from speculating about what God is up to and back towards each other and the suffering that we see before us. I wonder how if given the suffering that’s real if perhaps everyone in Job’s story, and in ours, would have been better served if each had shown up and operated out of what they could know for sure. This person is in pain. We are scared and unsure how to help. We don’t know why this would happen and we are angry and want to know how God can be in this. But we care for our friend and so we’ll listen to him and we’ll love him and cry and hope and wait and we’ll do all we can to comfort him and we’ll look for ways to make his situation right as best we know how. If we were to turn up in those ways much of the suffering we impose on each other would be minimized. The knowing that comes from consistently being with each other in those kind of deep and caring ways change the world. But instead it is too often the case that we like those friends try to save ourselves from the pain of it all by reaching for stories about how God measures and blesses our worth and what others have done to deserve their misfortune and what they must do to magically put it right. There are stories currently being played out that would have us stand back to assess blame and work from the assumptions that those who are suffering surely could have prevented this and are not our concern: Stories of how to treat the immigrant, the asylum seeker, the poor, the unhoused, the sick. Stories that leave them without the help they need because they don’t have the right connections, didn’t go through the channels, didn’t find the right job, didn’t keep their jobs, stay out of trouble, or save that nest egg. Last week a voice rose in response. It was, I think, the Spirit of our mothering God rising up in horror. It drew people to petitions and marches and prayer and wailing at the sight of children traumatized in this country’s name. Last week we saw pictures of children that we knew, pictures that cut through the stories we are told and that we tell ourselves. I remember and I felt again, as I looked at the picture of a little girl terrified, all the times I feared for one of my own children. Of all the times when I saw them in pain or scared and nothing would have prevented me from reaching for them and comforting them. Last week the voices that want to say but there are rules that we must follow were drowned out, if just for a little while, by a response called to life by the faces and cries of children in pain too close for us to deny. A different story broke through and there was a roar of defiance. Last week it was made even more clear to me that by getting close to the stories of those that we are conditioned to keep at a distance will in fact find what we need to get through. You see I knew that little girl. Hers was a story I was familiar with. I saw her as an ordinary little girl just like mine had been. I could see a family life full of good things. Love and learning, play and baths and sleepy dinners. I knew her. Her story was close enough and it reminded me and I think many others of who we are, what we want for ourselves and each other, and what we will not tolerate. As we find ways to get those who are normally kept at a distance as the complex, ordinary, beautiful people they are; as we find ways hear about their loves and their pains, their hopes and their fears, the more we will know the love that binds us, and the steadier we will feel, and the more prepared we will be to show up in love and mercy on behalf of those in pain. This is I am sure the way through the storm. It is the way of Jesus, the one who came to be with our story, to suffer with us, to heal, to give himself in love even when it didn’t make sense. These are stormy times. We are being battered by forces that tell us not to trust, to hate and blame each other, but like a mother who knows the pain and the utter joy that comes with loving the story of another, God will be with us. As we show up for others, even if it’s just looking for films that tell a fuller story, as we notice who is missing and learn about their ordinarily lives, the way they hurt and hope and love like we do, we will remember what is good and right and we will look for a better way ahead. Amen.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed