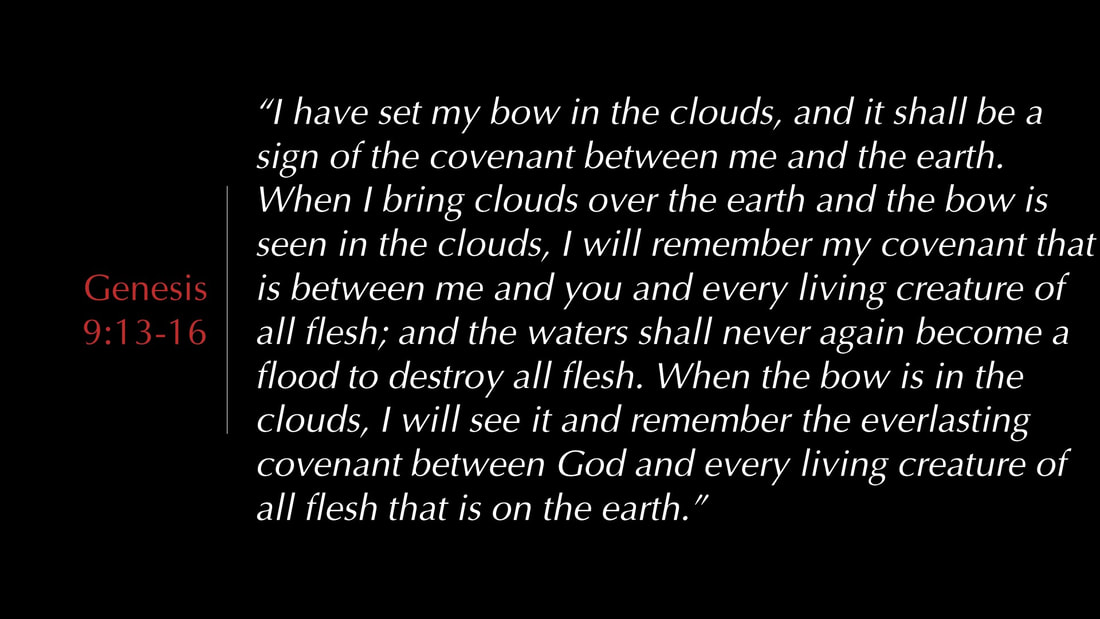

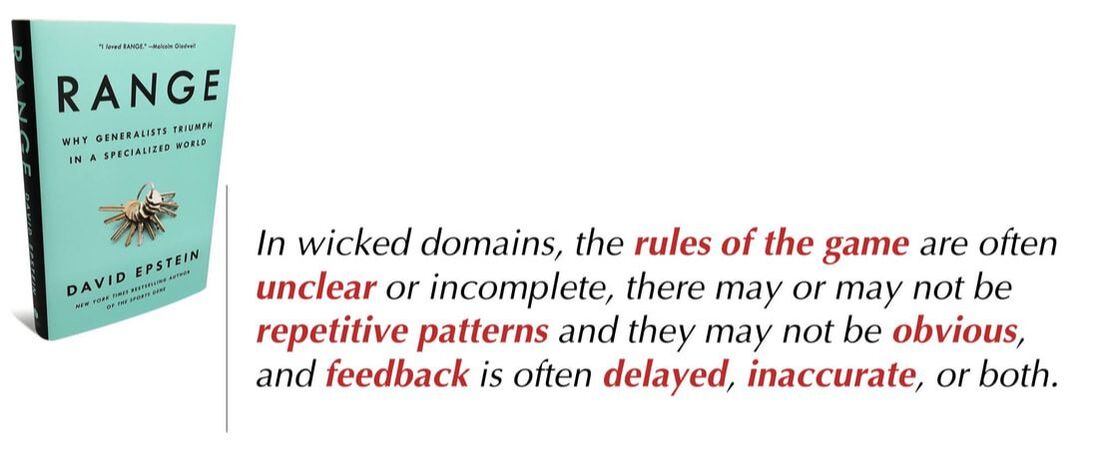

Scott AndersonGenesis 9:8-17 † Psalm 25:1-10 † 1 Peter 3:18-22 † Mark 1:9-15 A video version of this sermon can be found here. Here’s a pro tip for you. When it comes to learning, repetition is less important than struggle. This is the insight of what is known as the generation effect according to David Epstein in his book Range. Struggling to generate an answer on your own, even a wrong one, enhances subsequent learning.[i] It helps learning over the long-term in at least two ways—it makes it stick and it enhances our ability to apply our learning broadly. The struggle—doing the work—is the key. Epstein explains, “for learning that is both durable (it sticks) and flexible (it can be applied broadly), fast and easy is precisely the problem.”[ii] In terms of educational theory, you might say that the goal is to make it easy to make it hard. You want to create the right conditions that allow the struggle to go on without interruption, without fixing things in a way that short-circuit the opportunities we have for learning that will last a lifetime, learning that is both durable and flexible. I suspect our teachers know this concept well and you parents too, although it can be hard to create the right conditions. It goes against our instincts—perhaps especially in our culture, and especially within our context of privilege. We aren’t comfortable with having bewildered kids. Let’s be honest. We aren’t comfortable with being bewildered ourselves. We want understanding to come quickly and easily, but for learning that is both durable and flexible, that sticks and can be applied broadly, fast and easy is the enemy. John Gardner, the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare in the Johnson administration understood this—that possibilities are hidden like a pearl in an oyster—as he emboldened a nation to embrace the hard work and the hard soul-work of civil rights—a work which is far from finished in our own day. Epstein tells of a series of studies that illustrate this. Students were taught vocabulary in controlled settings that varied how they learned to explore the generation effect. Some were given words and definitions together. Negotiate: To discuss something in order to come to an agreement, for example. Others were shown only the definition and given a little time to think of the right word, even if they had no idea, before it was revealed. As you might guess, the students did better by far when they were not given the answer immediately, when they had to do their own thinking. This was as true for elementary kids as it was for college kids.[iii] Being forced to generate answers improves subsequent learning even if the generated answer is wrong. It can even help to be wildly wrong. [The study’s authors] repeatedly demonstrated a “hypercorrection effect.” The more confident a learner is of their wrong answer, the better the information sticks when they subsequently learn the right answer. Tolerating big mistakes can create the best learning opportunities.[iv] Here’s one take away from this important insight: we need to make it easier to make it hard. We need to create environments in our own homes and in our cultural environment—our schools, our politics—where it is ok to struggle. We have to be able to make mistakes and then have the space to learn from them, to fail spectacularly without devastating results if we hope to find our way to not only the answers, but to the implementation of them for our most devastating problems. I think there is something of this lesson that is written between the lines of our readings for this first Sunday in Lent. Struggle and suffering are everywhere here and the learning from them. It is surely uncomfortable for us to read the story of Noah in this context because it goes so against the systematic theology of modern Christianity that wants to control God, that defines God in terms that are other to human experience. If we are imperfect, God is perfect. If we don’t know everything God surely does. If we are impressionable and changeable, God is most certainly not. And yet here we find a story in which God literally repents. God commits to never again doing what God had just done in flooding the earth as punishment. “God said, ‘This is the sign of the covenant that I make between me and you and every living creature… I have set my bow in the clouds… I will remember my covenant… and the waters shall never again destroy all flesh… I will see it and remember.”[v] If you read the story closely, as it is written, the bow is there first as a memory device for God and secondly for humans. The covenant is a promise God makes. The generation effect is also written in the gospel reading, in-between the lines, as we compare Mark with the other gospels. Mark was written around the year 65, a generation after Jesus’ story was lived out on earth. It is succinct and always on the move compared to the other gospels. Consider everything that happens in today’s brief reading. There’s about one word for, for example, for every two days Jesus spent in the wilderness. The other gospels came later—over the next 50 or so years—shaping narratives that were more expansive and filled out as these early Christians continued to generate meaning from within their communities, as they tried to make sense of and application to new realities. You see, that’s the other thing about the generation effect. It doesn’t just help with retention, to make learning durable. It makes it flexible. The gift of the struggle helps us to adapt learning to new situations, to apply it broadly, to dance across disciplines, to learn not only from experience, but without experience in a rapidly changing, wicked world in which the rules are being rewritten, data is incomplete, patterns are absent, and feedback is unreliable. The struggle gifts us with conceptual reasoning skills that can connect new ideas and work across contexts.[vi]

We have been overwhelmed by a year of pandemic—I suspect far more than we realize. And this in the midst of a chaotic age in which many of our institutions, many of our assumptions, many of our agreements about a shared reality have been crumbling. Ours is a time not unlike that of those early Christians who struggled mightily to make sense of a new reality and a new and powerful story that had a hold on them in ways that would take time to figure out. It is tempting to see this as a moment of chaos and loss. I certainly hear that language a lot when it comes to the institution of the church and our fear that it is dying. But in a similar context something powerful was happening behind the scenes of that first century and I believe it is here in our own age as well. The question is whether we will work to create the conditions in which we can learn what we need, in which we become a part of the story, rather than an historical footnote to what is being birthed. In many ways, I am coming to understand that the problem of the church in this day is a white problem, a wealthy problem, a male problem. It is a problem unique to the church of the privileged who have leaned on a myth of supremacy that was never about faith but has always been rooted in control and exploitation and scarcity. It is white western culture that has never been able to face spectacular failure honestly, because that is to shatter the myth of supremacy. And that is now being ripped away. Beloved church, this is good news. Perhaps one of the greatest gifts of the chaos of this moment, and this Lent, is the gift of easing us off the illusion that our power, our control, our insisting we are better than we actually are saves us. The broad, big, long changes that we are facing are slowly tearing us away from our idolatry. The hope of this moment is that we may discover what it looks like to truly lean on God instead as a community of people, as a nation, as a human race with a deeply flawed past and a perilous future before it is too late. The Spirit is not absent. The Spirit is alive and active. The kingdom of God is fulfilled. Only two things were required to get Mark from Jesus’ baptism to this fulfilment—40 days in the wilderness and the arrest of John. What do you make of that? We have teachers all around us who know and have known this way and these deep truths. And Lent offers us another chance, a moment, to generate newness as we humble ourselves, as we fail spectacularly, even, and learn at the feet of others. Thanks be to God. Notes: [i] Epstein, David J. Range (p. 85). Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. [ii] Ibid., (p. 84-85). [iii] Ibid., (p. 85-86). [iv] Ibid., (p. 86). [v] Genesis 9:12-16, portions. [vi] Ibid., (p. 53).

1 Comment

|

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed