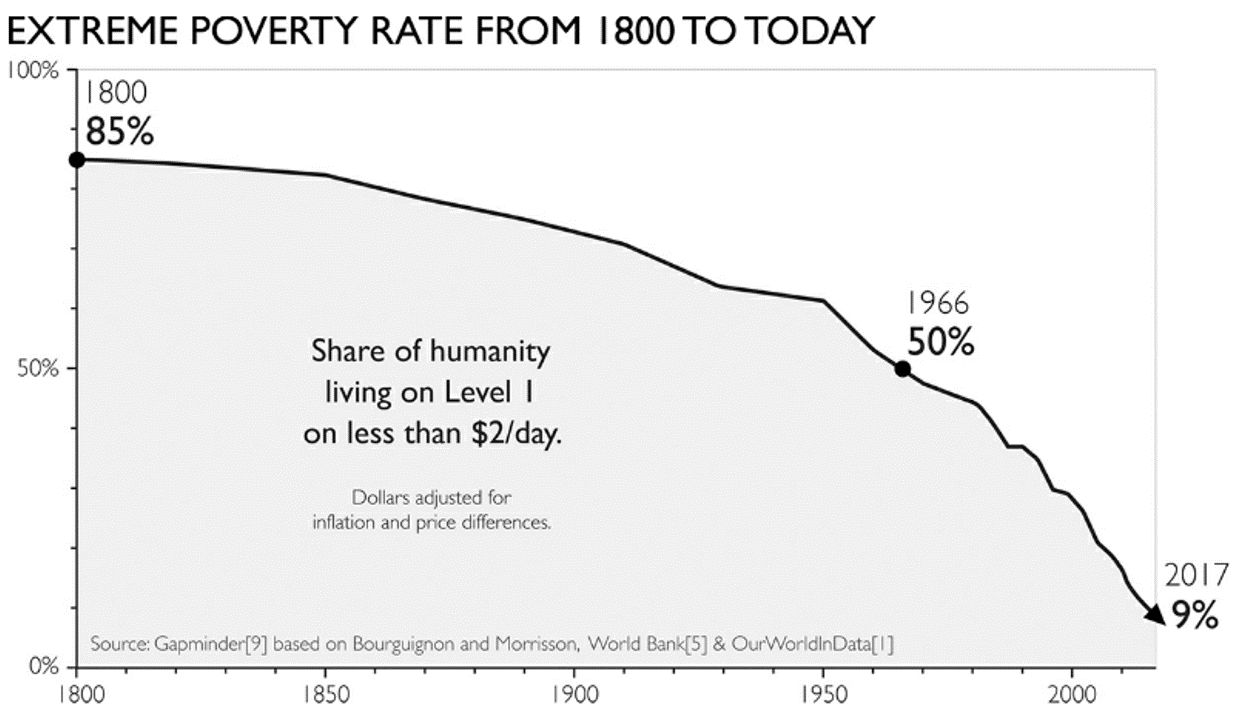

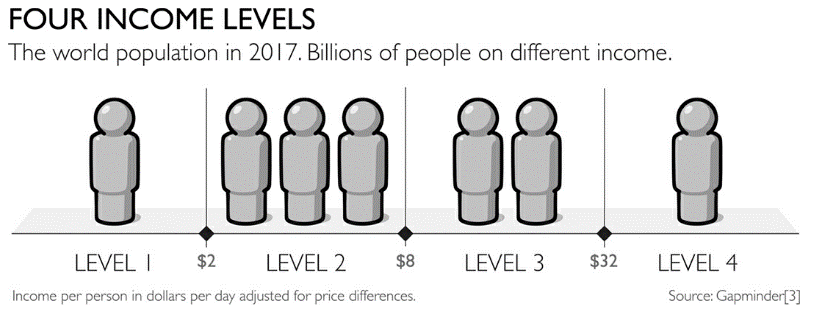

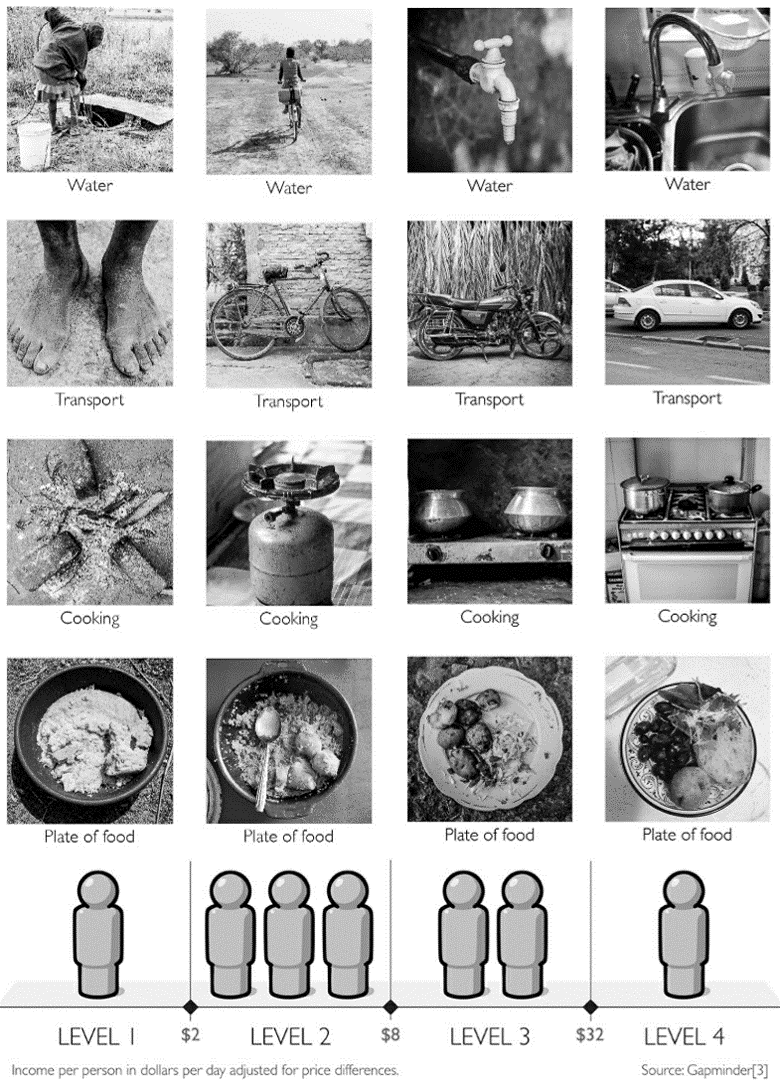

Scott AndersonIf you haven’t already, you may want to get to know these faces. These are neighbors of ours, young Americans predominantly from the northwest, with others scattered throughout the country. They range in age from 10 years-old to their mid-twenties. And they are suing the federal government for knowingly causing climate change and violating their constitutional rights. They are litigants of the youth climate lawsuit known as Juliana v. United States. Their complaint asserts that, through the government’s affirmative actions that cause climate change, it has violated the youngest generation’s constitutional rights to life, liberty, and property, as well as failed to protect essential public trust resources. The constitutional climate lawsuit was originally filed in Oregon in 2015 and has been making its way through the court system. The expectation is that the lawsuit will finally go to trial late this year, although that could change given the considerable resistance it has received from the federal government and corporate interests throughout the process. As best as I can understand, the lawsuit has found success in that it continues to move forward despite herculean attempts to dismiss the case. In one instance, for example, U.S. District Judge Ann Aiken submitted this finding: “Exercising my ‘reasoned judgment,’ I have no doubt that the right to a climate system capable of sustaining human life is fundamental to a free and ordered society.”[i] Now, don’t let anyone tell you true religion isn’t concerned with life here and now. What the judge is affirming is not significantly different from the hope of Isaiah who can imagine a world without misery in which the people know a life that is predictable and fair and fruitful. 21 They shall build houses and inhabit them; they shall plant vineyards and eat their fruit. 22 They shall not build and another inhabit; they shall not plant and another eat;… 23 They shall not labor in vain, or bear children for calamity; for they shall be offspring blessed by the Lord-- and their descendants as well.[ii] A paycheck that everyone can live on. Just reward for your labor. A future that is bright and full of promise in which hope and history rhyme. We may find ourselves wondering if these hopes are still possible given the facts on the ground, given what we’re told about how constrained and stretched we already are, given how supposedly limited our resources are. Last week we finished up a season of meetings with some folks who are newer to our congregation. Some of them joined with us as new members last night at the Easter Vigil, and we’ll introduce them to you today as well in just a little bit. One of our practices each week has been to spend time with the text for the coming Sunday, so last week, we were looking at today’s gospel reading. The way we titled it on our agenda generated a little conversation: An idle tale, they thought, according to Luke. Some scholars suggest that the word really carries an even saltier connotation. It’s BS. It’s fake news. And surely there is some hesitation to giving ourselves to the hope that is wrapped up in a future in which our kids can prosper, in a future economy in which people can afford to live in the homes they build and in the cities in which they work and not to have to choose between buying medications or paying the light bill. Surely there’s a way in which we and our descendants can live in some promise. Surely there is the hope of resurrection. No doubt you saw the news from Paris this week. The burning of the cathedral of Notre-Dame was profoundly distressing, and striking for breaking out in the midst of holy week. Surely this a sign of some kind. But a sign for what? The aftermath was rife with images and takeaways and reactions. An immediate response of generosity. Offers of hundreds of millions of dollars from obscenely rich families and corporations. And this, followed by a backlash that tapped into the current distress over the disparity in the distribution of wealth throughout the world. Yet this wasn’t the only story. We saw a spike in generosity from other corners of the world as well for other concerns. And with it questions about what kind of world we want, about what makes for the sustainable life that Isaiah envisions in the midst of idle tales, and fake news, and BS. In January, we learned that the world’s 26 wealthiest people now hold more wealth than the poorest 50%— 3.8 billion people.[iii] Can this be good for anyone? Are these the arrangements that will allow for people to inhabit the houses they build, and to eat from the fruit that they grow? Are these the conditions of a world in which people do not labor in vain or bear children for calamity? Do these realities give us confidence in a future that is a blessing to our children? These are, of course, not simple questions. Some of you will remember some of our conversations over the last year, with the work of the late Hans Rosling, captured in his book Factfulness. Rosling, notes that even with factually correct headlines like the one from Oxfam, it would be inaccurate to deny that the world population is improving its lot, increasingly moving out of absolute poverty toward better standards of living. For example, Rosling reminds us that “Over the past twenty years, the proportion of the global population living in extreme poverty has halved.”[iv] Not only is this revolutionary, he asserts, but it reflects a dramatic reduction that continues a long global trend beginning with the industrial revolution. You’ll remember that rather than talking about rich or poor, Rosling wants us to talk about degrees of poverty and well-being. He identifies four levels of income that result in profoundly different standards of living for our seven billion neighbors. You can see from this illustration the numbers of people, by billions, that currently live within these differing levels of income ranging from extreme poverty, which he considers as less than $2 per day, to relative wealth, which he pegs above $32 per day. And he helps us to visualize what life looks like within these four ranges. So, as of 2017, the best estimates are that about 1 billion of our siblings are living in extreme poverty, while about the same number of us live quite comfortably, with about 5 billion people living somewhere in-between.

But to know this is not to deny any other part of our reality, nor is it to miss that in the 1970s the divide between rich and poor began to expand again under current political and economic policies. Many Americans really do have to choose between their prescriptions and their electricity bill. That, ultimately, is Rosling’s point—and religion’s!—that the fullness of truth is what inoculates us from fake news in all its forms, and turns us toward what is ultimately possible. Isaiah says “do not remember the former things” because to engage in nostalgia, to “over remember” things, is to wall yourself off from the possibility of something new happening. And Luke, in his two-volume Luke-Acts story, warns us not to “under-remember” either. Hold onto hope. Remember what you have seen and known. Don’t give in to mental or spiritual laziness. Our future is at stake. Remember what Jesus taught you and what you saw of the possibility and power of neighborliness when God is in the mix—that the society we want is ours to form, and that this creating God has particular things in mind when it comes to the shape of this life. When we say that we believe in the resurrection of the dead, we are surely proclaiming that, no matter how much a person or a society has given in to destructive tendencies, new life is always possible with this Easter God, with this Spirit of life in the world and in us. In his book Rosling spends most of his time examining what is not true that we waste our time worrying about. But he also spends a little time addressing what we should be concerned with. Among those things he names global pandemics, a devastating world war with weapons of mass destruction, global financial collapse, and yes, climate change. And he adds, for good measure, extreme poverty where it still exists. With these concerns, he reminds us, as do these scriptures, to remember, and to remember truthfully. “There’s no innovation needed to end poverty.” Rosling writes. “It’s all about walking the last mile with what’s worked everywhere else.”[v] He is saying little different than what the gospel-writer is telling us. Little different than this biblical story tells us. Little different than this tradition tells us. To imagine that life on earth can be sustainable and peaceable when wealth is so profoundly skewed, when we are increasingly preoccupied by materialism and look to technology for security amidst increasing political unsettledness is to believe a fiction. This is fake news, an idle tale, if anything is. But to live in the hope of resurrection, is to remember what has been true before and can be again. With God, new life is always possible. Death—of any kind—is never the end. To live in the hope of resurrection is to make room once again for God’s new life to burst forth in your home and in our world. Why wouldn't you give yourself to it? Wendell Berry, the American novelist, poet, essayist, environmental activist, and farmer wrote a poem back at the beginning of the environmental movement when everyone agreed that climate change was something to concern ourselves with. I think it speaks as profoundly today as it did back in 1973. The first stanza is a warning: Love the quick profit, the annual raise, vacation with pay. Want more of everything ready-made. Be afraid to know your neighbors and to die. And you will have a window in your head. Not even your future will be a mystery any more. Your mind will be punched in a card and shut away in a little drawer. When they want you to buy something they will call you. When they want you to die for profit they will let you know. Then he leads us out with courage: So, friends, every day do something that won't compute. Love the Lord. Love the world. Work for nothing. Take all that you have and be poor. Love someone who does not deserve it. Denounce the government and embrace the flag. Hope to live in that free republic for which it stands. Give your approval to all you cannot understand. Praise ignorance, for what [humanity] has not encountered [it] has not destroyed. Ask the questions that have no answers. Invest in the millennium. Plant sequoias. Say that your main crop is the forest that you did not plant, that you will not live to harvest. Say that the leaves are harvested when they have rotted into the mold. Call that profit. Prophesy such returns. Put your faith in the two inches of humus that will build under the trees every thousand years. Listen to carrion - put your ear close, and hear the faint chattering of the songs that are to come. Expect the end of the world. Laugh. Laughter is immeasurable. Be joyful though you have considered all the facts. So long as women do not go cheap for power, please women more than men. Ask yourself: Will this satisfy a woman satisfied to bear a child? Will this disturb the sleep of a woman near to giving birth? Go with your love to the fields. Lie down in the shade. Rest your head in her lap. Swear allegiance to what is nighest your thoughts. As soon as the generals and the politicos can predict the motions of your mind, lose it. Leave it as a sign to mark the false trail, the way you didn't go. Be like the fox who makes more tracks than necessary, some in the wrong direction. Practice resurrection. Notes: [i] Quoted on the Our Children Trust website at https://www.ourchildrenstrust.org/juliana-v-us. Accessed April 19, 2019. [ii] Isaiah 65:21-23, excerpts. [iii] The Guardian. “World’s 26 riches people own as much as poorest 50%, says Oxfam” Retrieved on January 22, 2019 from https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/jan/21/world-26-richest-people-own-as-much-as-poorest-50-per-cent-oxfam-report. [iv] Rosling, Hans. Factfulness: Ten Reasons We're Wrong About the World--and Why Things Are Better Than You Think (p. 6). Flatiron Books. Kindle Edition. [v] Rosling, Hans. Factfulness: Ten Reasons We're Wrong About the World--and Why Things Are Better Than You Think (p. 240). Flatiron Books. Kindle Edition.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed