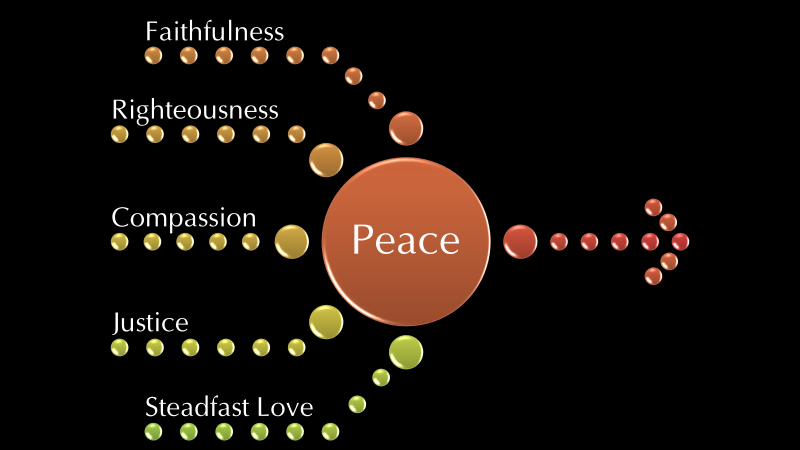

Scott AndersonActs 11:1-18 † Psalm 148 † Revelation 21:1-6 † John 13:31-35 According to local legend, the largest octopus in the world lives below the Tacoma Narrows Bridge. Some say it’s a 600-pound creature, once named King Octopus by The News Tribune.[i] Others say it lives among the ruins of Galloping Gertie, the wreckage of the bridge that collapsed during the November 7th, 1940 storm into the white-capped waters of the Puget Sound. Douglass Brown was 15 when he saw a giant tentacle emerge from Puget Sound. He was walking along the beach with a girl he wanted to impress when he saw this arm come out of the water. “It was 10, 15 feet in the air,” he told a reporter for KUOW. “It looked like an octopus or something like that, and I just took off running.”[iii] Not surprisingly, there is no report on how the relationship fared after that fateful day. “They try to scare you,” says commercial diver Kerry Donahue of these big octopi. “Their big defense mechanism [is that] they get bigger than you are.” The first time it happened to Donahue, it terrified him. “Because your radio is to the surface,” he told the reporter, “you take a lot of flak for screaming like a 2-year-old when you run into an octopus.” They can also get small, though. National Geographic set up a tank and shot a video to demonstrate how malleable these creatures are.[iv] They have an arm span of up to 20 feet, but because the only hard part of them are their beaks, they can squeeze their 600 pound bodies through small cracks and holes the size of a quarter. Once Donohue was working underwater with a team cutting metal with a burning rod. Another diver had a stack of rods nearby, but they kept disappearing. “He’s like, ‘I’m losing my rods. Where are they going?” And then he took a rod from his hand, held it out into the murky water, “and this tentacle comes snaking out and grabbed the rod and took it from him.” A New York Times article said this about a neighbor of the octopus: Sperm whales’ brains are the largest ever known, around six times the size of humans’. They have an oversize neocortex and a profusion of highly developed neurons called spindle cells that, in humans, govern things like emotional suffering, compassion and speech…Sperm whales live in close-knit societies; they are raised by matriarchal units that can include three generations; they appear to share regional dialects and family nicknames.[v] Yet, in the past 150 years, humans have killed off about 70 percent of the sperm whale population. Around 360,000 remain. That number is expected to drop even faster as the ocean warms and acidifies.[vi] Perhaps the ancient poet of Psalm 148 had a better idea then than we do now of the wonder of creation: I like the way the our gathering song captures the meaning: Let all that lives, all that has breath, sing the praise of God, hallelujah! whales doing backflips in the air, squid and octopi dancing under bridges; giant sequoias stretching to the sky, seals getting suntans on rocks Let all that lives praise God. This plea takes on new meaning, of course, as we hear ever-more exhaustive and dire evidence from international experts that we humans are speeding extinction and altering the natural world at an unprecedented pace.[vii] The novelist Tayari Jones had an article in an October edition of TIME Magazine, with a provocative title: “There’s Nothing Virtuous About Finding Common Ground”. She makes the argument that trying to “meet in the middle” is not the answer. “The middle is a point equidistant from two poles. That’s it,” she writes: There is nothing inherently virtuous about being neither here nor there. Buried in this is a false equivalency of ideas, what you might call the “good people on both sides” phenomenon. When we revisit our shameful past, ask yourself, Where was the middle? Rather than chattel slavery, perhaps we could agree on a nice program of indentured servitude? Instead of subjecting Japanese-American citizens to indefinite detention during WW II, what if we had agreed to give them actual sentences and perhaps provided a receipt for them to reclaim their things when they were released? What is halfway between moral and immoral? [viii] Jones brings us to our Acts text, and to a story that is far more important than we have tended to understand. The question the story presents us with is this: How did the church change its mind? Because there was no middle ground here. These early Jewish followers of Jesus were facing the kind of question that tears denominations and communities apart—the kind of question that gets people killed or, in the alternative, can heal a society. It was a sea change. Peter’s dream—the “pigs in a blanket” dream, as my friend Bob describes it—gets at the big deal: Everything these Gentiles ate, everything they did was different. For Jews to even associate themselves with these people, was a profanity. How in the world could they find any common ground to exist together, much less deal with the reality that they were being drawn to a life together by forces out of their control! This is the story, of course, that is replayed in some form every day on the news, it is replayed in your schools and your places of work and on Twitter and state assembly halls and in a thousand other places where there seems to be no room for compromise. And yet they found a way. That is why it is so remarkable, so astonishing. The story is only the last act of seven—a drama that takes up sixty-six verses in Acts. This is the longest single narrative in the book. And the story of this vision is told three times all together. First, in Acts chapter 10, we are told the story. Then in Acts 11, there is a story of Peter telling the story. Then, once he returns from his first mission to the Gentiles, in Acts 15 there is the story of Peter telling the story of the story that he had previously told them. So how did the church arrive at this turning point where cautious insiders were willing to risk their way of life to include outsiders, where those who were separate could become one? How did they arrive at this remarkable point of peacemaking where even the Gentiles found the “repentance that leads to life.” The answer, of course, is at a congregational meeting. Of course! A congregational meeting! How did we not see this? Well, perhaps this congregational meeting doesn’t provide an exact parallel to the one that will follow worship today, but there is something going on here. Peter has been called to account before the others: “Why did you go to uncircumcised men and eat with them?” Tell us you didn’t sell your soul; tell us you didn’t ruin our good name along with yours!” What is halfway between moral and immoral, Peter? Peter’s actions have threatened to tear the community apart, but what is so surprising is what happens next. He tells a story. He tells a story of a change of heart. Stories, not arguments, change lives. “You see all these unkosher things?” God says to Peter and us in his vision. “You see all these things that have defined your spiritual self at a fundamental level for your rejection of them? Well, start eating.” And stop making these bone-deep distinctions you’ve been making for millennia, and imagine yourself part of a new creation, a broader family that includes everything you thought unclean or even to be despised. It all changes now. The Acts story underscores the difficult challenge of change, and with it, I suspect, the slippery slope feeling when it comes to wholesale change and the fear of losing ourselves—whether it is one that has been held at the core of Judaism for generations upon generations, or other more recent challenges like our effect on the climate or the intractable debate over human life or gender identity in all its forms. Of course, sometimes the challenges are not quite as dire or well-reasoned, and this can help us to think more clearly about what we’re facing. How do we hold both the wide-openness of these texts of love and yet, not lose what else is essential about who we are The good news is that we do have something else to hold onto that helps us to refuse both the avoidance and denial that can be papered over in the language of “the search for the middle” and the fallacy of the slippery slope. There is an underlying substance to this faith of ours—a series of golden threads that stitch this story and our story together, a way of love enacted, enfleshed, that make a firm foundation of the slipper slope. There are deep values informed by story after story to which we are called to come back to again and again as we navigate our way. And while they do not tell us exactly what to do in every given moment or every age, while they do not invite us to cower at the top of the slope, but instead take the first step and then the next as we find our way, these values and the Spirit we find present in them and in us, give us solid footing by which we can negotiate the dips and turns and challenges we face in every age.

“I give you a new commandment,” Jesus said, “that you love one another. Just as I have loved you, you also should love one another.” And yet, it turns out it wasn’t really new at all. It was there all along, waiting to be rediscovered, remembered, and proclaimed. “By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another.” Thanks be to God. Notes: [i] See “Giant Octopus Revealed”, September 25, 2015 in Sound Magazine: http://southsoundmag.com/giant-octopus-revealed/. [ii] See “Is there really a giant octopus under the Tacoma Narrows Bridge?” April 19, 2016. Retrieved May 17, 2019 from https://kuow.org/stories/there-really-giant-octopus-under-tacoma-narrows-bridge/. [iii] See “Is there really a giant octopus under the Tacoma Narrows Bridge?” April 19, 2016: http://kuow.org/post/there-really-giant-octopus-under-tacoma-narrows-bridge. [iv] See nationalgeographic.com/video/octopus_cyanea_locomotion. [v] James Nestor. “A Conversation With Whales” April 16, 2016, New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/04/16/opinion/sunday/conversation-with-whales.html. [vi] James Nestor. “A Conversation With Whales” April 16, 2016, New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/04/16/opinion/sunday/conversation-with-whales.html. [vii] See, for example, Brad Plumer’s “Humans Are Speeding Extinction and Altering the Natural World at an ‘Unprecedented’ Pace” in The New York Times, May 6, 2019. Retrieved on May 17, 2019 from: https://nyti.ms/2J4zwfQ. [viii] Tayari Jones, “There’s Nothing Virtuous About Finding Common Ground”, TIME Magazine, October 25, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2019 from: http://time.com/5434381/tayari-jones-moral-middle-myth/.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed