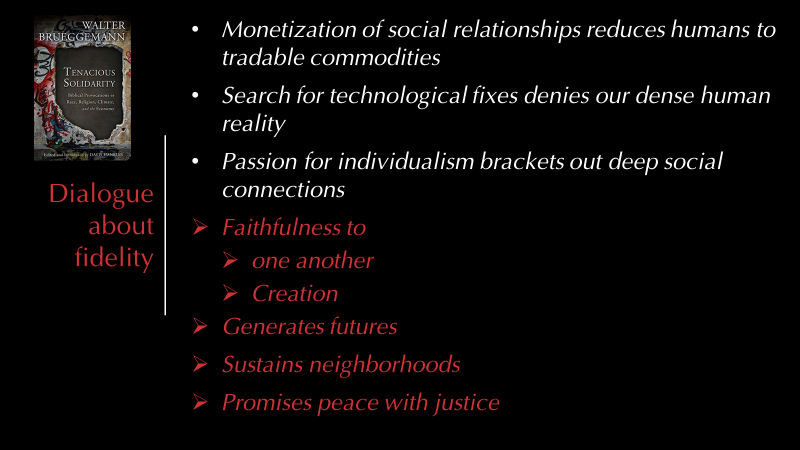

Scott AndersonActs 9:1-20 † Psalm 30 † Revelation 5:11-14 † John 21:1-19 If you were here last week, you may be wondering what we’re doing reading another section from the Gospel of John. “Didn’t we finish that last week?” you might ask. And my response to you is to say, give yourselves a pat on the back for your insightful and close listening. We should all be proud! Check out the last paragraph from chapter 20, the previous chapter in John, from last week’s reading: Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not written in this book. 31 But these are written so that you may come to believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that through believing you may have life in his name.[i] It is clearly the ending to the story—a hopeful summary statement by the gospel writer reminding us what the work of Jesus’ disciples has been about. Case closed. Time to move on. And then we have this afterthought: After these things Jesus showed himself again to the disciples by the Sea of Tiberias… It reminds us, of course, of the alternate endings to Mark’s Gospel, which, as we will remember, the careful readers we are, seems to try to “fix” the rather unsettled ending to Mark by having Jesus offer a great commission or appear to Mary Magdalene. Biblical scholars tell us these alternate endings are most surely later editions from scribes who wanted to make things a little easier. And, although they are included in our bibles, they are included with flashing neon caution signs warning us these endings are absent from the most ancient resources, and they are rarely read in our assemblies. There are no such warnings in John, although these same scholars have long debated the origin of the chapter. Not only does it continue after a clear summary statement, but the writing style and theological imagery is different and it bears close parallels to the story of the catch of fish in Luke 5[ii]. Loaves and fishes remind us of those feedings of the multitudes. If this is original to the gospel, then we should assume a number of hands over a period of time ultimately shaped John. Yet these concerns do not keep us from these stories. In fact, unlike those add-ons in Mark, we seem to love them and have paid close attention to them over the ages. And I am among this group. It feels a little to me like someone has thrown open the windows and doors that were closed in the previous stories set in locked, stifling rooms that the risen Lord had to get into as if by magic—walking through walls and finding a way in past locked doors, forgiving sin, breathing peace to you and you, and see my hands and my feet and believe even and especially as you are racked by fear and gasping for hope. And then we suddenly find ourselves out in the open—along the sea. We can lift up our eyes and see for miles. And not only that, we can settle into the comfort of known routines and remember life goes on. And that’s where the disciples are, back to fishing, back to what they’ve known. I don’t know about you, but many of my dreams have turned rather dark these last few years. For me, there is something of a pall over our life, and it takes its toll. And one of the things I’ve noticed is the gift of coming to work, of coming to be with you, of returning to a place where I’m invited to lift my gaze from my own concerns and doubts, to those who are in front of me and precious, to the privilege and joy and even the struggle and certain unpredictability of being with others. My spirits are lifted as they are when I find myself in an expansive wilderness, drawn to this wide and sublime beauty that can never be fully captured by words, but buoys my soul. And we seem to get that here, don’t we? An expansive lake, a wide world filled with possibility and promise. And an experience of memory and forgiveness and challenge that elevates these disciples, reminds them of what they have seen and known, and fills them with courage and purpose that is echoed in the heavens: “Worthy is the Lamb that was slaughtered to receive power and wealth and wisdom and might and honor and glory and blessing!”[iii] Blessing and honor, glory and might, forever and ever. By the end of the story, all that doubt is once again washed away for Peter as he splashes into the sea as if he is once again baptized and new, and for the other disciples as well as they are filled again with the possibility of this One and this story. And I love that this story, unlike the others the past few weeks, is not set on a Sunday. It is not an eighth day. It is not the first day of the week. It is just sometime “after these things.” It’s after the commute. It’s in the middle of the work-week. It’s while you’re doing your chores, or running to the grocery store, or watching Youtube or taking a hike. It’s that unexpected, unremarkable time when God just shows up, uninvited, and reminds us what’s possible, and asks again, “Do you love me?” Are you still a part of me? Do you remember what you’ve seen and heard? Are you strong again? There is something profoundly humane about this story. There’s gentleness and generosity that shows up quietly, not advertising itself, but there for the taking—a calm morning, a breakfast prepared, a warm fire, a respite in the midst of the work day. Bread offered, companionship. There’s no public shaming here. There’s no storm. No one draws a sword or even engages in a battle of wits. Jesus’ conversation with Peter is honest. It does not shirk from the truth, but his prodding elicits a largeness in Peter’s spirit that he didn’t know he possessed prior to that moment. The only viciousness we see is in Acts with Saul as he breathes threats and violence against the disciples of the Lord as if this is in his very nature, as we imagine it is in those we have identified as our adversaries. And yet, even here, it is Saul’s ultimate awareness of the loving sacrifice of the Christ, and the astonishing hospitality of those early Christian followers who take him in, that transforms him into Paul, who like Peter and the many women, became one of the foremost examples of courageous discipleship and social change in early Christianity. I believe that, even in these times, there is remarkable room for us to practice generosity and kindness even as we seek to be truth-tellers. If there is a hallmark of Christianity according to this gospel, it is the tenacious commitment to the value of all life. It is the persistent commitment to humanize our reality in the midst of the dehumanization so common in our current cultural moment. Walter Brueggemann provides something of a summary of this dehumanization and Christianity’s counter in his book Tenacious Solidarity, which you’ve heard me refer to before. He notes that we are witnessing a monetization of social relationships, which make our relationships transactional rather than relational. As a result humans become objects—tradable commodities in which inequality can flourish and vulnerable people are sacrificed. Likewise, he suggests we are witnessing in our breathless search for technological fixes a denial of our dense human reality. Our hope for simple fixes ignores, he says, the “organic” and decidedely complex “truth of the human body and the body politic.” Finally he suggests that our passion for individualism reduces our imagination to myopic categories of money, commodity, and technology. Questions of fidelity—of our belonging and our deep, organic connection to one another have been largely bracketed out. The counter to these onslaughts of dehumanization, Brueggemann asserts, is the “continuation and maintenance of a dialogue about fidelity”—about our faithfulness to one another and to this creation—“as an urgent task. It is that dialogue that generates futures, that sustains neighborhoods, and that holds prospect for peace with justice.”[iv] Muhamad Yunus, the Nobel Prize-winning economist and “banker to the poor” echoes Brueggemann’s sense in deeply practical terms. In his book A World of Three Zeroes he reminds us that the persistence of poverty, unemployment, and environmental destruction is not a matter of natural calamities. These are choices that speak to human values. They are matters within human control. They are failures of our economic system, which was created by humans, after all, and so can be corrected. Remember,” he says,

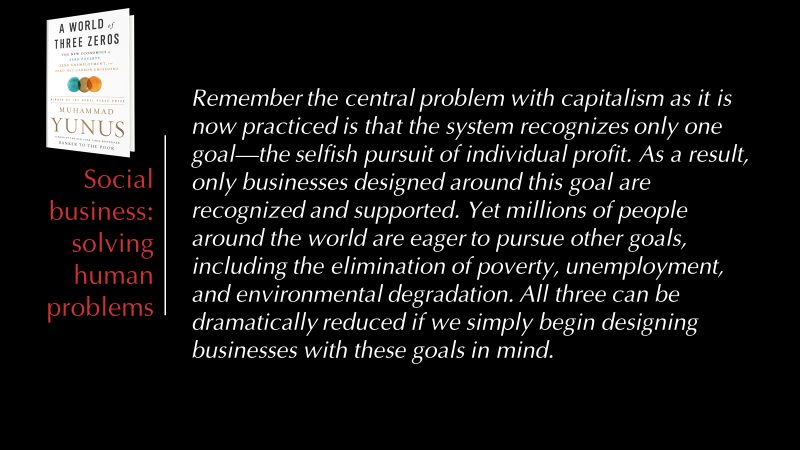

the central problem with capitalism as it is now practiced is that the system recognizes only one goal—the selfish pursuit of individual profit. As a result, only businesses designed around this goal are recognized and supported. Yet millions of people around the world are eager to pursue other goals, including the elimination of poverty, unemployment, and environmental degradation. All three can be dramatically reduced if we simply begin designing businesses with these goals in mind.[v] Yunus defines businesses that have human welfare in mind as social businesses, which he defines simply as a non-dividend company dedicated to solving human problems.[vi] I love this story from John because it reminds us that God is God not just in here on a Sunday where we remember this story, where we share this bread and drink this cup and are reconstituted as Christ’s body for the world. God is the God of all creation and all human life—at work and at play, in the day-to-day moments when we sometimes imagine we are on our own. We are not. This is the good news of Easter. Life is always waiting to burst forth. The Spirit is always ready to rise again in you for the sake of the world. Amen. Notes: [i] Luke 5:4-11. [ii] John 20:30-31. [iii] Revelations 5:12. [iv] Brueggemann, Walter. Tenacious Solidarity (Kindle location 7369ff). Fortress Press. Kindle Edition. [v] Yunus, Muhammad. A World of Three Zeros: The New Economics of Zero Poverty, Zero Unemployment, and Zero Net Carbon Emissions (pp. 39-40). PublicAffairs. Kindle Edition. [vi] Yunus, Muhammad. A World of Three Zeros: The New Economics of Zero Poverty, Zero Unemployment, and Zero Net Carbon Emissions (p. 27). PublicAffairs. Kindle Edition.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed