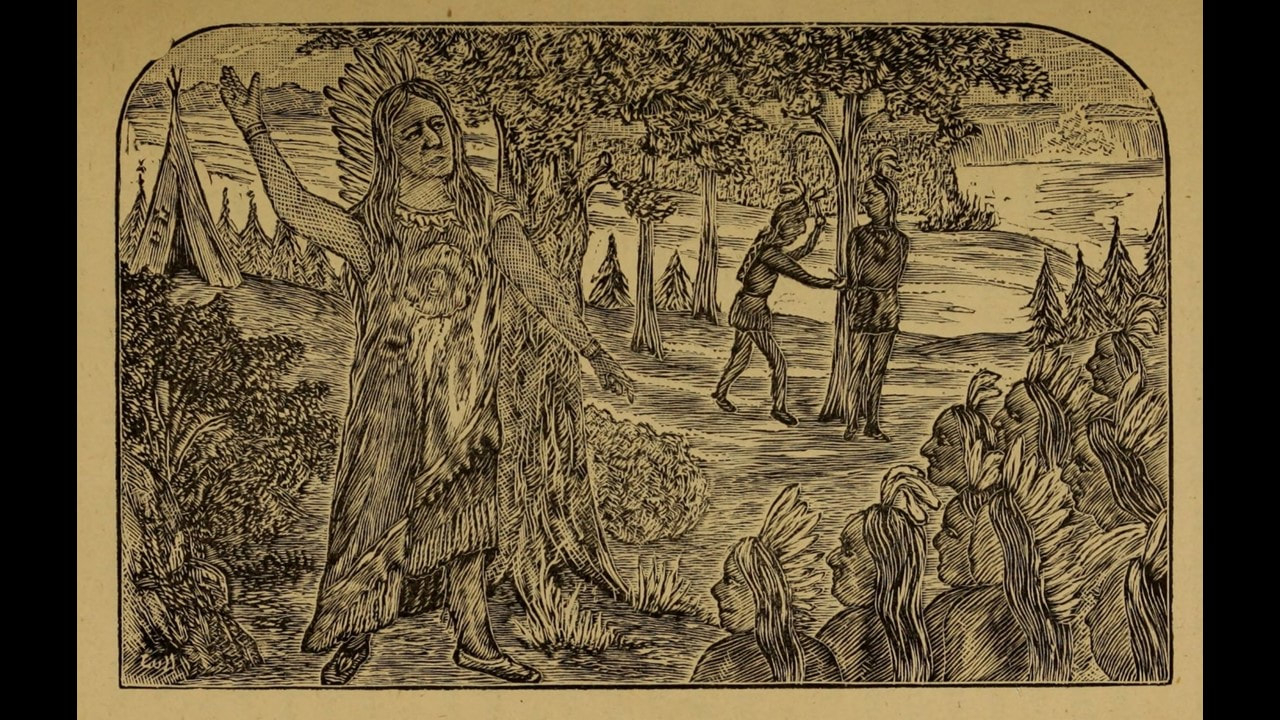

Scott AndersonIsaiah 5:1-7 † Psalm 80:7-15 † Philippians 3:4b-14 † Matthew 21:33-46 Long before our country was founded, this land belonged to the many indigenous tribes who had lived here for thousands of years. The tribes had their own customs and laws. They were deeply connected to the land and maintained rich wisdom traditions that were lost on the Europeans who came to conquer and colonize to sow a trail of tears through the continent. It is also true, of course, that even before European colonization, they fought one another. They were not unfamiliar with the cycles of violence we often find ourselves trapped in. One of the reasons for the constant conflict was a practice known as “mourning wars.” Tribal people had come to believe that the only way they could ease their pain when someone they loved was killed was to return like for like, to take revenge—to kill people from the offending tribe. One day, as the story goes, Hiawatha, an Iroquois chief was wandering the forest, mourning the death of his daughters and plotting his revenge. That’s when he met Deganawidah, also known as Peacemaker. When he spoke words of sympathy and compassion to Hiawatha, Peacemaker offered him a new way to deal with his grief. Hiawatha’s weeping stopped. Peacemaker said that more killing only led to more grief. People instead should offer words of kindness and gifts of sympathy as the way to deal with grief. Hiawatha was changed. He gathered all five Iroquois chiefs and told them of Peacemaker’s message. They came together gathered around a white pine tree for a ceremony where Peacemaker stood in their midst. Peacemaker pulled the tree up by its roots, leaving a huge hole in the ground. He told all the warriors to throw their weapons into the hole as a symbol that they would not fight any more. They did so, and the terrible “mourning wars” were over. When we make peace with each other today, someone may say we have “buried the hatchet.” That saying comes from this story. The wisdom of the Iroquois tribes enabled them to work and live together largely in peace with each other. They even tried to teach the lesson to the representatives of the thirteen colonies who came together in Philadelphia for the first Continental Congress in 1776. The chiefs shared their stories of the Tree of Peace and urged the colonists to unite.[i] Some of you may remember when we first told this story way back in 2008. At the end of worship we went out into the yard and planted a tree on that Sunday to remember that story and the call it shares with our own faith to ways of forgiveness that lead to peace. Before we placed our tree in the ground, we placed symbols of our own acts of peacemaking, we buried our own hatchets under the root ball of that new tree. As we know all too well in these days of chaos and uncertainty and perhaps the most tension and conflict this country has known in our lifetimes, peace is a fragile thing that is only as strong as our next act of self-giving, our next act of advocacy, our next act of forgiveness. And it is no simple thing to hold out the ideal of peacemaking and goodwill toward others, without giving up the idea of justice. Well, here’s a rather embarrassing thing: That tree that we planted back in 2008 is long gone. Over time the branches turned brown. It began to show signs of disease and neglect. I should note that I wasn’t the only one who noticed. Around that same time, before I had said anything to anyone, I saw Andy Resor dragging a garden hose across the front lawn to bring water to it. You can just see the tree in the background of this 2011 picture of Bob Seel. Alas, it did not survive. It was eventually replaced in 2013 by one of the lovely crabapple trees that now line the street on the church property. And yet, this does nothing to take away from the fact that those symbolic “hatchets” we buried together on that day are still buried. And we have buried others since then. And it makes a difference. Each act makes a difference and does not get lost in the arc of history. You probably remember the trouble the 49er quarterback Colin Kaepernick got into a few years ago when he started to kneel during the anthem before NFL games. It has not gone well for him personally. It effectively marked the beginning of the end of his football career—at least to this point. But consider how we have advanced in our conversations around the systemic structures of racism that have persistently privileged white lives over those of black and brown lives. Consider how the issue of police reform has become a national conversation in a way it was not when Kaepernick first began to kneel and got punished for it. Just because something starts out quietly, or is unpopular at the beginning, it does not mean it will end that way. “In Iroquois society,” says Wilma Mankiller, the first female chief of the Cherokee Nation, “leaders are encouraged to remember seven generations in the past and consider seven generations in the future when making decisions that affect the people.” [ii]

As we consider these texts for today, especially this deeply challenging and unsettling parable that Jesus tells to a group of church leaders that are, to be plain, already plotting to kill him, I am reminded that this faith of ours does not deny the power of evil—nor the ways in which religion and governance can be misshapen into a tool for violence and malice. This landowner and this faith are not naïve. The Late Night host Seth Meyers commented this week on the news that came out about the president and his taxes. Four years ago as a candidate, Meyers noted, he bragged about how his avoidance of taxes made him smart. Meyers rightly corrected that his ability to hold onto his wealth and not pay his fair share, while perhaps not illegal under a tax system that provides all sorts of loopholes for the privileged, does not in fact make him smart. It just makes him powerful. “There are plenty of smart people who pay their taxes in full every year, he said, because they don’t have the arm of accountants and lawyers rich people like Trump or companies like Amazon have.”[iii] And while we certainly hope and pray for health and well-being of the president and his wife, as we do for all of those who are suffering mightily in the midst of this pandemic, our genuine compassion does not require us to lose sight of the unsurpassed care they will receive that many others do not have access to, nor the mixed messaging and reckless behavior that has sowed chaos and presented a clear and present danger to many others who have crossed their paths. Nor does this story of ours deny the hope faith has that the justice and goodness of God’s kingdom has even greater power, is a far more compelling and life-giving way, and ultimately prevails. Here is the thing that I am most struck by in this story—it is the persistence of the vision of the landowner. It is the unwavering, unfailing belief of the landowner that the abundance of the vineyard can be made available to everyone. It is the persistence of this One who imagines a world that does not compete for resources, but shares them, that does not get lost in the death spiral of senseless rivalries, but builds coalitions and realizes better and better outcomes through creative partnerships. It is the vision of a creation that simply has no experience of fear but moves forward freely and confidently, from strength to strength. I so miss that we are not able to gather together these days around the table. It is, you see, no decoration and it is no weapon. It is a gift, a physical sign of the landowner’s vision of sufficiency and abundance—that every time we come to it we remember that we are fed because we hunger, we remember we are given a community to eat with because we need one another. We remember we join with the church throughout the world as Christ’s body broken for the sake of others, Christ’s life poured out for creation, a river of life flowing from the sanctuary to heal the nations. This is our way to God and to one another. This is our way to peace. That has not changed. And it will not. Thanks be to God. Notes: [i] Sources: White Roots of Peace by Paul A.W.Wallace, Clear Light Publishers, 1994; Linking Arms Together by Robert A. Williams, Jr., Routledge, 1999. Found in 2008 Peacemaking Offering resources (PDS 11142-80-288). [ii] “Greetings All, In Observance of American Indian Heritage Month.” USDA Forest Service. Retrieved on October 2, 2020 from: https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/npnht/news-events/?cid=FSEPRD480422. [iii] “Late-night TV roundup” The Guardian, September 29, 2020. Retrieved on October 2, 2020 from: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2020/sep/29/stephen-colbert-donald-trump-hair-late-night-tv. Recording retrieved on October 2, 2020 from: https://youtu.be/MufkLBSzE3Q.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed