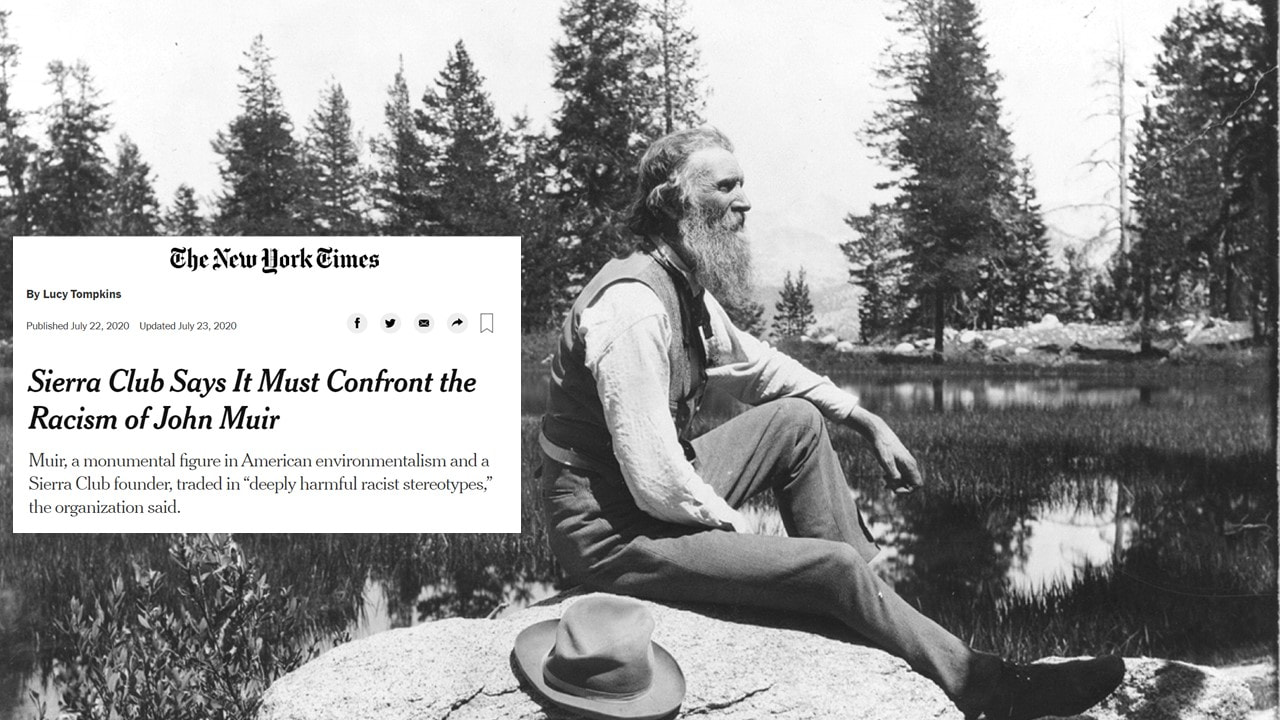

Scott Anderson1 Kings 3:5-12 † Psalm 119:126-136 † Romans 8:26-39 † Matthew 13:31-33, 44-52 The naturalist John Muir once said, It is a powerful sentiment, one that resonates deeply with me, and I suppose is one of the reasons I am drawn to those yearly walks in the woods that I’ve just come back from. There’s something deep to experience. A sensibility, an understanding that words more often than not fail to unearth. But it’s there, beneath the feet. Deep underground, and yet, all around, if we choose to see it. It hasn’t been a good week, though, for our friend John Muir. Muir is a hero of American conservation. Schools throughout the country bear his name. Countless hikers have walked the 200 miles of the John Muir Trail through the Sierra Nevada. His writings have inspired generations of naturalists and along with Aldo Leopold and Rachel Carlson, shaped the preservation movement that grew the American National Park system.[ii] But he also trafficked in deeply harmful racial stereotypes and propagated the ideal of the lone white man in the wilderness at one with nature, that not only misses the deep connections of all life, but has supported the system of white supremacy and done great harm. Lucy Tompkins, in this recent article offers us this reminder: Some of Muir’s writings characterized Black Americans and Native Americans as dirty and lazy, and while white settlers had already forcefully displaced many Native Americans from the Yosemite Valley by the time Muir arrived, he considered their presence in the Sierra Nevada as a blemish on an otherwise picturesque landscape.[iii] I suppose it is not unlike the story of Solomon that we encounter in the first reading this morning. Here we have that beatific vision of a king who is an inspiring leader. Humble. Filled with wisdom and faithfulness. A righteous person, perhaps. Longevity, wealth, and vengeance are all absent from his wish list. We should also be so discerning, and so fortunate. We know that these stories were compiled and edited together during one of the worst periods of Israel’s history—in the midst of Babylonian exile. Everything had fallen apart. The mythology of Israel’s exceptionalism as uniquely chosen and blessed by God had decayed. There was a need to remember, to reshape the understanding of those who had lost so much to provide meaning, and some hope and courage to a defeated people. It remains a remarkable example of pastoral work that teaches us and perhaps inspires us in our own time of disorientation. The problem, though, is it wasn’t true. At least not completely true. If you look closely at the text, and around the edges, you can see it. There are hints of the way in which Solomon tried to have it both ways, how he succumbed to the pull of his own need for greatness. Forced labor, the concentration of wealth in one place, religious zeal filled with compromise. His was a governance that was ruined by idolatry and indulgence. And the end result was the tearing apart of a fragile alliance of the 12 tribes of Israel that would never be put back together again. We can, of course, see the value of origin stories that remind us of our ideals, of who we aspire to be, but when they are divorced from the true and complex realities of our lives and our histories, they can create even greater problems. Being able to tell the difference between good and evil lies at the heart of many biblical narratives. The second creation story (Genesis 2-3) is a good example. It is worth noting that there were many trees in the garden, among them the tree of Life and the tree of knowledge. Here, though, is what I’ve missed before. On the same tree, the tree of knowledge, two types of fruit—good and evil—grew together. Wisdom, it seems, is no simple thing. Discerning the difference between good and evil is often an ambiguous choice that brings a series of catastrophic consequences.[v] But this is no reason to despair. Only to look more closely. To look deeply at our story, to examine the edges, to look to the past and face it fully that we might have a future to live into. And even more importantly, to see what has been there all along, out of sight, underneath our feet, giving us roots to grow. Consider the mustard seed, Jesus teaches. It is such a small thing. A tiny seed, and yet it grows into something massive that provides shelter and shade and preserves life. It is a lovely image, but as you may remember, the Mustard plant is no real beauty. It’s a wild herb at best, a common weed, really. Gardeners spend their days trying to rid the garden of such things, but it keeps growing, spreading, festering. Life refusing to be tamped down by some flawed notion of how things ought to be. If Jesus were really on our game, he would have gone with the Cedars of Lebanon that Ezekiel celebrates, or the Doug Fir of the Cascadia forests. But he goes with this Mustard Shrub instead, that attracts not those apex birds of prey that mount up with wings of Eagles, but tiny birds that proliferate under these branches and eat up all the gardener’s good seed. It’s not quite what we are looking for, and I suspect makes the scenario at the end of this story in which Jesus asks if the disciples understand, and they answer confidently, “YES” one of the funniest lines of the Bible. We work so hard to bracket out anything that reminds us we are not in control, suggests Tacoma pastor Kris Rocke, when the truth seems to be that God “comes to us through the very things we work so hard to eliminate.”[vi] We so carefully cultivate a fragile, idealized vision of our selves when, in reality, God is blessing us through what we curse and dismiss and find inconvenient and even shameful. It is in the trouble, amidst the curse—fruits of good and evil side-by-side—by which salvation comes. This is the hard and holy context in which Paul can preach that all things work together for good. So we are again invited to look closely. Look into what we prefer to avoid, into what we would rather ignore than dig and get dirty for. Because like that big weed, like that yeast that makes its way throughout the dough, it isn’t going away. And even better it grows as a blessing if we give ourselves to it: the governance of God bubbling up to make us whole, reminding us we are one with it, a part of it, a part of each other and the whole of creation.

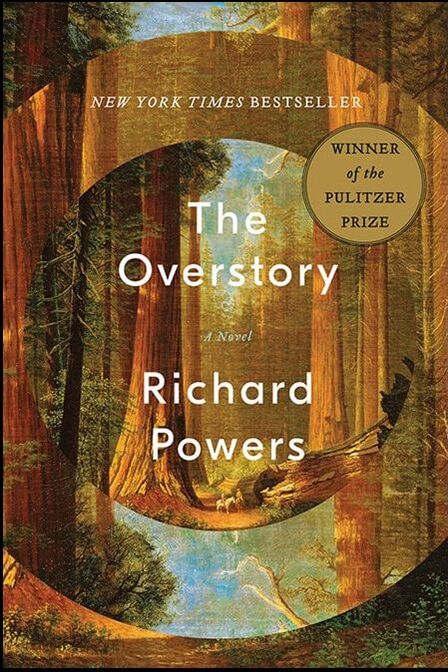

forest that has been preserved for research exists outside of the book as the Olympic Experimental State Forest and the work as that of federal research stations like this one. Using his characters, Powers tells us compelling stories of nature and what it might possibly mean for humans and our own governance and existence, and perhaps even the governance of what Jesus called the Kingdom of God.

Dr. Westerford finds her true home among a group of researchers she first encounters studying a dead log: “How long have you been at it?” she asks them. The two men trade looks. The younger man hands down another sample bottle. “We’re six years in.” Six years, in a field where most studies last a few months. “Where on earth did you find funding for that long?” “We’re planning to study this particular log until it’s gone.” She laughs again, a little wilder. A cedar trunk on the wet forest floor: their grad students’ great-great-great-grandchildren will have to finish the project.[viii] Now, I don’t know if funding like this truly exists, but it strikes me as one of those things that is so beautiful it must be true. In the story, Dr. Westerford gives herself to the research of the (slide 14) Douglas Fir, one of the patriarchs of our Cascadian forests. Let’s pick up the story here: The things she catches Doug-firs doing, over the course of these years, fill her with joy. When the lateral roots of two Douglas-firs run into each other underground, they fuse. Through those self-grafted knots, the two trees join their vascular systems together and become one. Networked together underground by countless thousands of miles of living fungal threads, her trees feed and heal each other, keep their young and sick alive, pool their resources and metabolites into community chests. … Her trees are far more social than even Patricia suspected. There are no individuals. There aren’t even separate species. Everything in the forest is the forest. Competition is not separable from endless flavors of cooperation. Trees fight no more than do the leaves on a single tree. It seems most of nature isn’t red in tooth and claw, after all. For one, those species at the base of the living pyramid have neither teeth nor talons. But if trees share their storehouses, then every drop of red must float on a sea of green.”[ix] Our lives are connected, deep underground, often out of our view, but it is no less true. Our kinship, according to Powers, “work[s] like an unfolding book. The past always comes clearer, in the future.”[x] Such is the way of our creator, such is the work of salvation, if we dare to look deeply for it. Amen. Notes: [i] Powers, Richard. The Overstory: A Novel (p. 124). W. W. Norton & Company. Kindle Edition. [ii] See Lucy Tompkins “Sierra Club Says It Must Confront the Racism of John Muir.” First published July 22, 2020 in the NYTimes. Retrieved on July 24, 2020 from: https://nyti.ms/2CWEqd2. [iii] Ibid. [iv] Genesis 2:9, NRSV. [v] Feasting on the Word: Year A, Volume 3: Pentecost and Season after Pentecost 1 (Propers 3-16) (Feasting on the Word: Year A volume) (p. 705). Presbyterian Publishing Corporation. Kindle Edition. [vi] Kris Rocke. Street Psalms blog, “Changing the Metaphor.” July 24, 2020: https://streetpsalms.org/. [vii] See this UW web page, retrieved on July 24, 2020: https://environment.uw.edu/faculty/jerry-franklin/. [viii] Powers, Richard. The Overstory: A Novel (p. 139). W. W. Norton & Company. Kindle Edition. [ix] Powers, Richard. The Overstory: A Novel (p. 142). W. W. Norton & Company. Kindle Edition. [x] Powers, Richard. The Overstory: A Novel (p. 132). W. W. Norton & Company. Kindle Edition.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed