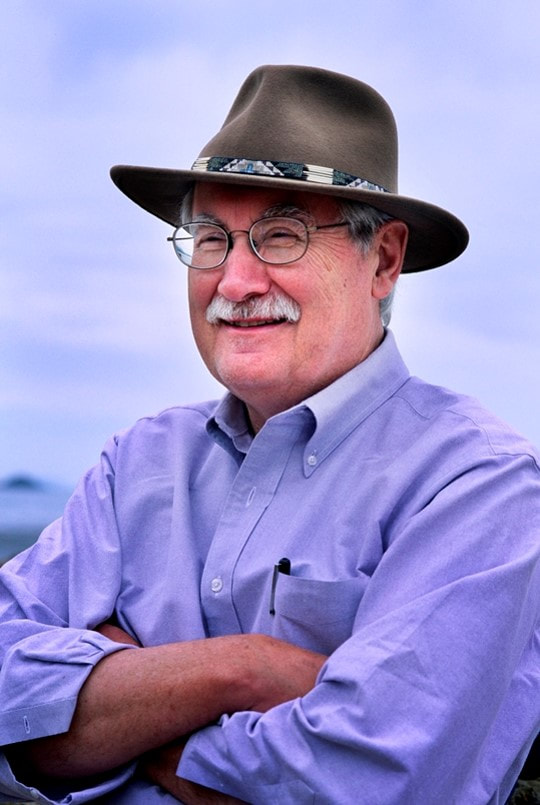

Scott Anderson

Franklin and a team of researches visited the scorched slopes of Mount St. Helens after the volcano exploded with the force of multiple atomic bombs in 1980. William Dietrich tells the now familiar story in his Pulitzer Prize winning book, The Final Forest.[i] The blast laid trees over like a giant comb, burning off the needles and covering the mountainsides with logs like matted brown hair. Ash covered the duff of the forest floor. Humans and large animals caught in the blast were suffocated and roasted. But scientists were surprised at how many small creatures and plants survived the searing heat and began immediately to repair the ecological fabric. Fireweed poked through the ash. Ants scuttled across the gray powder. Gophers burrowed to the surface, beginning to mix the old soil with the new deposits. Insects and seed began to blow across the moonscape. Dietrich’s book is about the great logging battles of the 1980s and 90s. I remember them well because my uncles and cousins on my mom’s side were in the thick of it, dependent on logging and forest service jobs that looked to our ancient forests to produce the wood that built our country’s homes in the 20th century. If you don’t remember that, you probably remember the spotted owl.

For years the sense of best practices shifted. Forests were seen as little different from the massive farms that provide our food, just one more crop to be harvested and replanted in absolute uniformity. So forests were clear-cut and then replanted with a sea of identical saplings. Jerry Franklin and his team changed all of that when they looked out over a moonscape of volcanic ash that had once been old growth, and discovered something more. Ants scuttling across the gray powder. Gophers amending the bad soil and making it fertile as they burrowed to the surface. They discovered a rich, fertile, durable ecosystem. Dietrich continues the story: It dawned on the scientists that leaving woody debris behind speeds the recolonization of the forest after a disturbance, be it volcano or clear-cut. Musing later on the twists and turns of his life that made him one of the Pacific Northwest's most famous and controversial scientists, Franklin remarked on the propitious timing of the eruption that jolted ecologists' thinking: if the blast had not leveled those 150,000 acres of trees, the campaign to preserve millions of additional acres of forest may not have developed quite the same way. That story got me thinking about this one, and about what seems to be at first some pretty depressing odds, or, if you prefer, a pretty poor performance on the part of this sower who casts his seeds far and wide—recklessly, we might say—finding success only 25% of the time. On the path, on rocky soil, among thorns. All this seed, wasted. What farmer is this careless? What sower would waste such precious seed.

Pete had dug the hole after he died. It was a perfect hole chiseled with some effort through the layers of rocky soil and clay that make our back yard such a pathetic place for growing much of anything. I suspect it may have been just the kind of physical work he needed to do to say goodbye. A labor of love. Oh, here’s my current favorite picture. I really think it captures his best, part alien side, don’t you? After we buried him, I had my own moment. I took the mixture of rock and clay and dirt that was left over and I sifted it to separate out the rocks. I bought some peat moss and vermiculite and mixed it with what was remaining, and ended up with a mixture that I think would have made a gopher proud. And that’s when it hit me. Soil doesn’t just stay the same. The army of gophers and worms amend the soil far better than I ever could, transforming vast acres of rocky soil into fertile fields ready to bear the seed to a bountiful harvest. And those paths. Anyone who has walked along a forest trail knows that those paths are constantly in danger of being swallowed by tree and plant that know no boundaries. And the birds survive on the seeds that they find. It is almost as if this world is not a factory farm, but a rich, vibrant ecosystem that is constantly in motion, recklessly scattering seed, yielding new life, rewriting the story. Perhaps a little carelessness is warranted when it comes to the seeds we scatter. Perhaps we are the soil. Sometimes rocky, sometimes weedy, sometimes ripe for the harvest. Maybe this careless, reckless farmer knows a little more than we do—giving the story to the likes of these imperfect, conflicted, weedy people—Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebecca, Jacob and Esau, me and you.

And just maybe it isn’t about us anyway. Maybe its about this whole ecosystem and our role in the cycle, doing our part in making for life, fertilizing the seed, preparing, watering, tending, harvesting, and blessing. Taking the worst we see in our politics and our relationships and our societies, and amending it through faithfulness and love. Womb and tomb of this dazzling creation God has created the church to care for. The only mistake we could make would be to think it is about us, rather than about this great goodness of which we are a part, this ancient forest, this sublime creation that was here long before we were, and will be long after we find ourselves once again one with the dust and ashes, fertilizer for what comes next. Beloved of God. Do not fear this time. Do not doubt that the Sower is sowing seeds of life far and wide. Only continue in this way. Give your life away and watch it come back to you. Amen. [i] Dietrich, William. The Final Forest: The Battle for the Last Great Trees of the Pacific Northwest (Penguin Books, 1992), 99.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

St. Andrew SermonsCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed