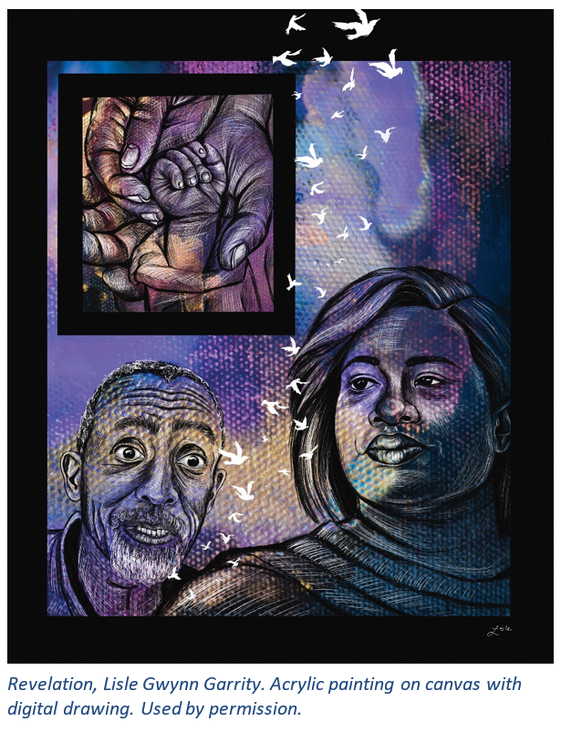

The old man held the boy, but the boy held the old man. ~ Antiphon from the Feast of Simeon Ritual is something of a dirty word in these days in which institutions and their traditions are in question. There is, surely, good reason for the distrust that has grown around our institutions—all of them, our religious ones among them! Traditions and their rites are designed to bless society, to pass on life-giving mores and practices, to ensure that justice and equity and wonder and peace have a firm hold on us, that we progress in the ways that make for life to the full. When they don’t, when they have lost their value, then a change is going to come. It must! The tension, then, that we are presented with in these ancient texts is deserving of our attention. Here this family, with their child of promise, their child of revolution—the “consolation of Israel” is presented, and Anna and Simeon, representing all that has been, all that was, see in this moment what might be: “This child is destined for the falling and the rising of many in Israel, and to be a sign that will be opposed so that the inner thoughts of many will be revealed—and a sword will pierce your own soul too.” How does a weary world rejoice? I would guess soul by soul and day by day. But if you ask me, I bet most of it counts. ~Sarah A. Speed @writingthegood, December 4, 2021 How does a weary world rejoice? We root ourselves in ritual. In ritual, that is, that prepares us for what is to come, that opens us to the wisdom that holds us in our weariness, and that compels us to life abundant, no matter what must be sacrificed for it. Enter into worship this Advent Sunday. Readings: Isaiah 61:10-62:3 † Psalm 148 † Luke 2:21-38 About the art: Revelation. Lisle Gwynn Garrity. Acrylic painting on canvas with digital drawing. Inspired by Luke 2:21-38. Used by permission.

From the artist:

I wonder what Mary and Joseph expect when they enter the temple to dedicate their newborn son. This customary ritual quickly unravels into an astonishing scene. A stranger named Simeon pronounces Jesus to be a “light” and “revelation,” and his dying wish is fulfilled. A prophet named Anna also draws near to the child, praising God for the redemption he will bring. Simeon and Anna’s words fill Mary and Joseph with amazement. But that can’t be the only emotion taking up space in the room. For Simeon turns to Mary, perhaps privately, to continue sharing his message: the boy will also become the cause of great turmoil, the catalyst for opposition. He will expose the inner thoughts of many. A sword will pierce her innermost being. The mother of God will grieve as she bears witness to the suffering of the child she birthed. In this image, Simeon bestows his blessing and prophecy with the urgency of a man desperate to say everything that needs to be said before his time runs out. Anna looks off into the distance, as if peering into the future. Her devotion to God over the years has sharpened her gaze; she knows redemption when she sees it. In the top left, I depicted Jesus’ hand being cradled by the hands of his parents. This tender moment is frozen in time, like a Polaroid photograph placed in a scrapbook. Mary and Joseph treasure their child as they receive the fullness of his calling. I imagine them memorizing each wrinkle and tiny fingernail, treasuring the smallness of a hand that will one day become a strong fist, fighting for justice for the oppressed and liberation for those held captive.

0 Comments

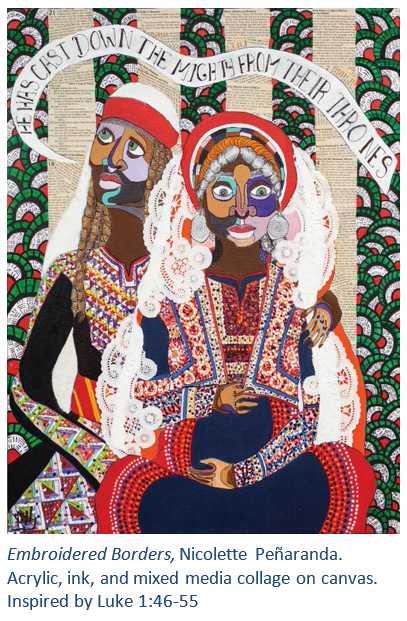

My heart shall sing of the day you bring. Let the fires of your justice burn. Wipe away all tears, for the dawn draws near, and the world is about to turn. ~Canticle of the Turning, Rory Cooney, 1990 How does a weary world rejoice? One answer is while singing songs of hope. Or to be more specific, singing together songs of hope. Hope for a world where there is no more war, no more hunger, no more crying, no more homelessness. No more of all the things that we seem to have taken a millennium or two to try and navigate and that are still present. So what is it about the people’s song that seems to be so important? This week’s readings include two of the central canticles (sacred hymns) of the birth narrative in the Gospel of Luke: the song of Mary (Magnificat: I magnify) and the song of Zechariah (The Benedictus: Blessing). So much singing! And in the daily prayers of people throughout the world, these canticles are sung every day. We now know that singing together makes things happen. Our heart rates start to match up, our anxieties lessen, and communities are formed. The science of it all is something that singers have known all along. Our Christmas celebrations are sometimes planned around singing and music. If it was good enough for the angels, it must be something we do too! But singing is something we also do to keep going when times are tough, when we are weary. We know of singing during times of protests. In our country, the civil rights movement was filled with songs of hope, songs of what the new world could be like. We also know that songs can be something that distracts us from reality. We can be nostalgic for carols that take us out of the world, that takes the humanity out of Jesus (no crying he makes?) , or are just too much fun to sing for us to also think about the text. “O Holy Night” has a verse that is left out many times because it is too “political.” But the birth of John and the birth of Jesus were smack dab in the middle of political times where the powerful threatened the voiceless people with torture and death, many times to keep them voiceless. And yet, the people continue to sing. Readings: Zephaniah 3:14-20 † Luke 1:46-55 † Luke 1:67-80 Join us for worship. Sunday morning at 10:00am in-person or online. About the Art: Embroidered Borders, Nicolette Peñaranda. Acrylic, ink, and mixed media collage on canvas. Inspired by Luke 1:46-55.

From the Artist:

Two years before the birth of Jesus, during the Pax Romana, one of the worst public executions happened a half day’s walk away from where Mary grew up. She came of age during a time of occupation, more than likely unable to recall a time of true peace and liberation. Mary’s song rings of a dream that not only she but her ancestors dreamed of, and she would be the one to give birth to the savior of her people. Fast forward thousands of years and the same land where Mary grew up is still being occupied. One can imagine that the cries for liberation and the prayers for justice still ring down the streets of Bethlehem. To me, Mary’s song of praise is still valid for the women of Palestine and for the people who still raise their children under the duress of war and occupation. This image is a nod to Palestine. The background operates as a foundation, built with the colors of the Palestinian flag and with collaged scriptures that celebrate women. Elizabeth and Mary are both in Palestinian regalia but from different generations. Elizabeth, centered and holding her belly, is in an outfit inspired by a photograph of a woman from Ramallah, dated sometime between 1929-1946.4 This was intended to emphasize the generational differences between the two. Mary, on the other hand, is in more contemporary Palestinian fashion. A stipple effect was used to highlight the intricacy of Palestinian embroidery in both garments. What felt important to me is the placement of Mary and Elizabeth. Rarely does Elizabeth get to be the center of the story, as her pregnancy becomes an accompaniment piece to the birth of Jesus. But here, Elizabeth is in the foreground. She gets to be the star while Mary places her arms around her, comforting her, and proclaiming the good news of what is to come. Mary is the hope that we see in all youth.  What was achieved in the body of Mary will happen in the soul of everyone who receives the Word. ~ St. Gregory of Nyssa, 4th century There is something about Christmas Eve and its worship. It is a comfortable space for many, and many of us—especially in times of such upheaval, in times of weariness—crave the familiarity and company of tradition. Those carols and hymns that ring with such strong affirmation, that hold us in the deep, in the mystery and awe of (in the Northern hemisphere) our longest nights. When it is hard to see with our eyes, we long to look to our memories and our stories for visions of what holds us. How does a weary world rejoice? We make room. We make room for memory. We make room for new life. We make room for family. We make room for one another. We make room for all who wander and wonder looking for home. Enter into worship this Christmas Eve. Readings: Isaiah 61:1-4, 8-11 † Psalm 126 † Luke 1:57-66 About the art: Surrogacy. Hannah Garrity. Oil paint, charcoal, and copper leaf on canvas. Inspired by Luke 2:1-20. Used by permission.

From the artist:

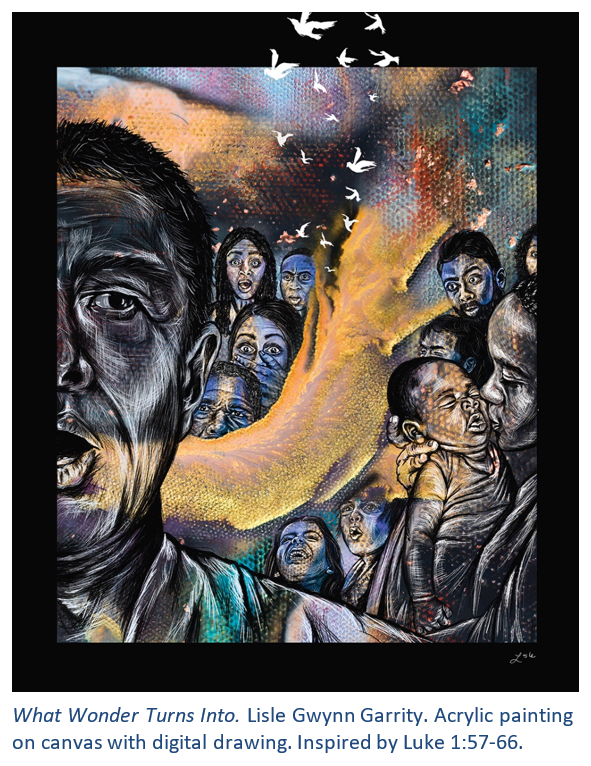

Dr. Christena Cleveland published a book in 2023 called, God is a Black Woman.5 In it, she shares her powerful testimony describing her journey to meet the Black Madonnas carved centuries ago from lava rock. This resonates with my lifelong yearning for Mother God. Male language for God has always been a wall to my ability to connect in worship. Now, it is a wall that I break through every week—changing words, rewriting liturgy in the moment, saying “Mother” where “Father” is printed, trying “Lady” where “Lord” is printed. In this case, “Yahweh” is actually best. Who are we to squash God into patriarchy so perpetually? But when someone else joins me in this necessary work, that is when the barrier is removed. I hear it sometimes: “She,” “Mother.” Almost always, the liturgist feels the need to explain themselves. In liturgy discussion, gaslighting is common. “We should be more inclusive.” All of a sudden? Recently, I was standing at The Dwelling at Richmond Hill.6 The former slave quarters are open and offered for visitation. After our tour, the idea that one should remove their shoes before entering this holy haven came up. Our tour group was all white people and we discussed this idea from a theoretical standpoint. But earlier, before we entered, I felt it. I was holding a seltzer water can from lunch and felt incredibly rude entering the space with it, so, without understanding, I backtracked and placed my purse and the can outside. I knew not why. After the tour, in our discussion about shoes, our white tour guide mentioned that Black members of the staff felt a great reverence, a holy presence at The Dwelling. The space held the presence of God; it was like entering a sanctuary. I remember the same feeling when I was young, touring the slave quarters at Monticello. But now, listening to the Richmond Hill staff testimony, I understood these spaces in a new way, with a reverence for the God-like presence of the Black mother in the depths of oppression. “Listen to Black women.” This cry has become a mantra over the last few years. I saw in that moment what Cleveland so eloquently explains in her book. In the pigmentocracy we inhabit, the Black mother is the closest figure to God, and “whitemalegod” is the very farthest. He promotes oppression; She is the savior of the most oppressed. And so I listen. In this painting, Black Mother God has asked her daughter Mary to hold the role of surrogate for the pregnancy of infant Creator. Mary has carried the child to term. She has given birth. God embraces Mary as well as the Holy Infant in gratitude. For without Mary’s surrogacy, the incarnation could not be.  people come and people go – the earth goes on and on the sun rises, the sun sets – it rushes to where it rises again the wind blows round, round and round – it stops, it blows again all the rivers run to the sea, but the sea is never full – from where the rivers run they run again these things make me so tired – I can’t speak, I can’t see, I can’t hear what happened before will happen again I forgot it all before. I will forget it all again. ~ again (after ecclesiastes), David Lang, 2005 The Hebrew Bible is composed of three sections: the five books of Moses, the Prophets, and the Writings. It has the same books as our Christian Old or First Testament but they are ordered just a bit differently. While all these texts play a role in Jewish worship, five books from the Writings are associated with and provide structure for Jewish holidays through the year. The scriptures have, in other words, a liturgical function, charting the course of human experience through the year and from one year to the next in the midst of the assembly. The deeply philosophical book of Ecclesiastes provides the context for Sukkot, the feast of booths or tabernacles, a harvest feast that occurs in the first month of the civil year (usually September or October in our calendar). The book is read aloud in some synagogues as a part of the celebration. Sukkot, then, is both end and beginning in the yearly cycle of Jewish worship. The modern composer David Lang was struck by the linkage of Ecclesiastes with a fall harvest celebration. In his notes on his 2005 piece titled again (after ecclesiastes)—performed to powerful effect by the Northwest Chamber Chorus this season—Lang reflects: “Somehow it seemed very poignant to me that Judaism might link together such a dark and philosophical text with a joyous religious festival celebrating abundance.” He embraced the idea that these celebrations, like our own Christian celebrations chart a cycle of celebrations that move us from one year to the next. They underline the breadth and depth of human experience. Lang again: It seems to me that the point of connecting each book to its holiday is that these books are very human, very personal. Much of religion is mysterious and unknowable, but these books are all about people and their emotional lives – life and death, courage, love, companionship, regret. His complete work the writings, written over the course of 14 years, reflects this awe-inspiring cycle of human life and human emotion. He begins and ends with the movement again (after ecclesiastes), yet the score “instructs the performers to sing it differently. The cycle, like the year, may repeat, but never exactly.” How does a weary world rejoice? I would guess soul by soul and day by day. But if you ask me, I bet most of it counts. ~Sarah A. Speed @writingthegood, December 4, 2021 How does a weary world rejoice? We allow ourselves to wonder at this world, at this human experience, at the ebb and flow of loss and gain, death and new life. We allow ourselves to be amazed. And like old Zechariah and Elizabeth, it may change us forever. Enter into worship this Advent Sunday. Readings: Isaiah 61:1-4, 8-11 † Psalm 126 † Luke 1:57-66 About the art: What Wonder Turns Into. Lisle Gwynn Garrity. Acrylic painting on canvas with digital drawing. Inspired by Luke 1:57-66. Used by permission.

From the artist:

When was the last time you were truly amazed? I don’t mean surprised; there is much about this world that should shock us. I mean amazed—wrapped up in wonder, absorbed in an unexpected delight. I love witnessing the moments when my one-year-old daughter allows amazement to wash over her like a gentle rain: her jaw drops open, her eyes widen and stay fixed, and for a rare moment, she gets very still. This recently happened when she discovered the kids across the street playing basketball for the first time. Her senses have not yet grown dull to the magic surrounding her. In this image, I wanted to capture the moment Zechariah’s voice returns to him. I decided to depict only half of Zechariah’s face; this miracle is not really about him, but about what happens through him. When he confirms John’s name, he sheds his distrust of the angel’s impossible news. His skepticism and weariness subside as he awakens to the joy in his midst. He allows himself to be amazed. Zechariah’s voice pours out of him, parting the surrounding crowd like the Red Sea, stirring each person into confusion and bewilderment. The blessing of his song spills over to his son, who is held tenderly by his mother. Elizabeth is the only person in this scene who is not presently swept up in wonder. I believe Elizabeth has spent months allowing herself to be amazed. She was in isolation for the first five months of her pregnancy (Luke 1:24). Perhaps she needed that time to go inward—to heal from the trauma of her infertility, to trust the promise of life in her womb, to attune herself to her child. She was capsized with awe the day Mary showed up at her doorstep. And so, when Zechariah’s voice returns, Elizabeth’s senses have not grown dull. Instead, her amazement has metabolized into something new: attunement for her child. It has transformed into love and deep trust. It has turned into joy. When we allow ourselves to be amazed, we might be surprised what that wonder can turn into.  Enter into worship this Sunday at 10:00am in-person or online. Readings: Isaiah 40:-11 † Psalm 69:30-36 † Luke 1:24-45 About the Art: Two Mothers, Nicolette Peñaranda. Acrylic, ink, and mixed media collage on canvas. Inspired by Luke 1:24-45. From Sanctified Art (sanctifiedart.org). Used by permission. From the artist: A couple of months before I took on this project, I was forced into early labor and birthed our second child. Needless to say, I was still pretty raw with emotions and was processing the trauma. During that time, I found myself in isolation. Our days were spent driving back and forth to the NICU to check on our 3 lb. infant. It was terrifying and tiresome. But during that time, so many wonderful people sought us out. We were gifted food, baby clothes, childcare, and rest. But the greatest gift was the comfort I received from other people who had given birth. There was this sacred sharing of birth stories and postpartum depression. Parents passed on beautiful garments that they, too, received after birthing a preemie. Some of these pieces looked like they had been passed down many times before, like each thread held a memory from a different family. We were connected. It is because of this connection that parents share that I felt instantly connected to paying homage to Frida Kahlo’sTwo Fridas. Rather than being connected from veins of the heart, Mary and Elizabeth would be connected through the uterus. Nearly a quarter of Black women between ages 18 and 30 have fibroids while also being the racial demographic with the highest maternal death rate in the United States. More than 100,000 women undergo some form of mastectomy each year. Globally, an estimated 14% of girls give birth before the age of 18. Where do these realities meet the heart of scripture? How do we see the struggles of infertility or empathize with the vulnerability that comes with not being a socially-accepted pregnant person? While Elizabeth is crowned with holy gray hair and a dress marked with the blood of previous miscarriages, Mary sits next to her holding a childhood doll, draped in the jewelry, flowers, and silks of a traditional Middle Eastern Jewish bride. Their stories and experiences are vastly different. But Mary sought out her kin. This reminds me that we do not need to do the hard things alone. There is power in connection.

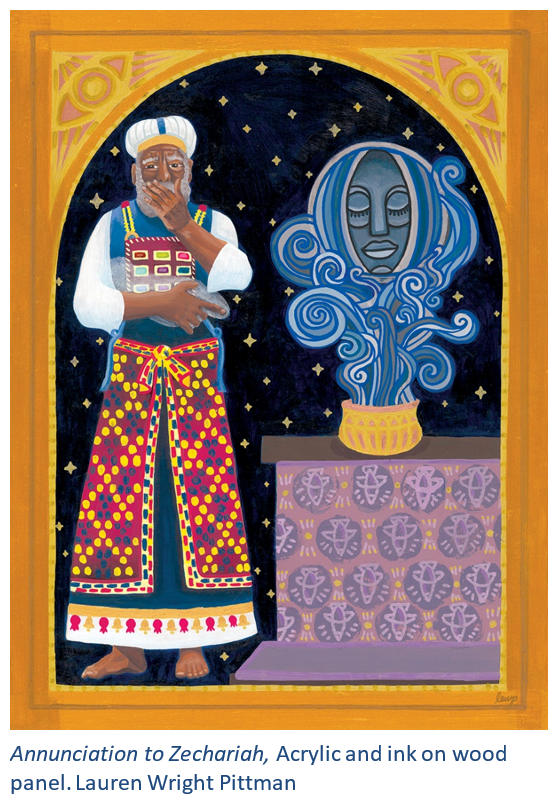

O Holy Night! the stars are brightly shining; It is the night of the dear Savior’s birth. Long lay the world in sin and error pining, Till He appeared and the soul felt its worth. A thrill of hope- the weary world rejoices… ~O Holy Night, Placide Cappeau, 1847 How does a weary world rejoice? This is a live question for us as Advent once again breaks into our yearly cycle. Weary, to be sure! There are no shortage of events and conditions and realities that we can point to as catalysts for our weariness. So this year, we are straying a little from the usual cycle of readings to attend to a few stories in Luke that don’t get as much attention, to ask how do we rejoice in this moment? Where does hope and resilience come from? To ask, how does a weary world rejoice? As we move through the season we will propose some answers to the question. This first Sunday, Advent 1, we sit quietly with Zechariah (and Elizabeth) and a text that does not make it anywhere into the lectionary cycle and suggest that a weary world rejoices by acknowledging it’s weariness. And so shall we. May we too rejoice. How does a weary world rejoice? I think delayed Christmas cards count-- the ones with the haphazard stamps, mailed three weeks late. I think the way you get down on all fours to be close to your dog And your cousin’s baby counts; it’s a holy routine. I think the way you stretch your body awake and breathe deeply when you rise counts; that’s Yahweh in your lungs. I think the extra second you spent looking at the sky last night, and not being afraid to dance counts. So does giving up your seat on the subway for someone’s grandfather, helping her carry the stroller up the stairs, and running to catch the man who dropped his bag in the crosswalk. Lighting candles when the sun disappears, laughing so hard others begin to stare, and pausing to look at trees every once in a while to say “Good job with that one God” all definitely counts; as do mumbled prayers and children’s prayers and every measure of music. How does a weary world rejoice? I would guess soul by soul and day by day. But if you ask me, I bet most of it counts. ~Sarah A. Speed @writingthegood, December 4, 2021 Enter into worship this Advent Sunday, in-person online. Readings: Isaiah 64:1-9 † Psalm 80:1-7, 17-19 † Luke 1:1-23 About the Art: Annunciation to Zechariah, Lauren Wright Pittman. Inspired by Luke 1:1-23. From Sanctified Art (sanctifiedart.org). Used by permission. From the artist: Zechariah stands in the Holy Place wearing the most meticulous of garments. Does he expect to encounter the divine? Or is he just going through the motions, lighting the incense as an all-too-familiar scent fills the air?... I ruminated on this image… a weary priest wrapped in layered fabrics, colors, symbols, textures, and rare stones that proclaim God’s providence and power. The contrast is not lost on me… I often try to neglect my weariness by putting on a veneer of unwavering trust in God—while feeling like I may suddenly unravel into a pile of beautifully-curated threads, stones, and gold accessories.

|

worshipYou'll find here links to weekly worship and, where applicable archived service videos. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed