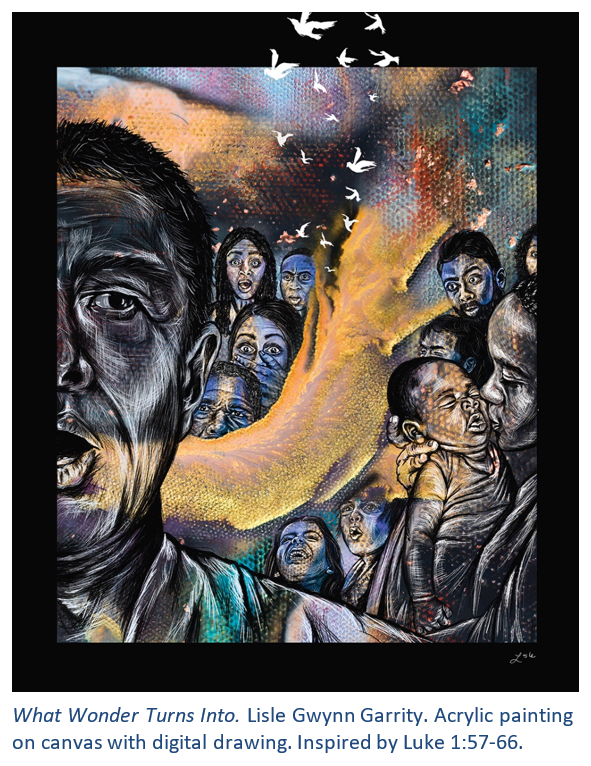

people come and people go – the earth goes on and on the sun rises, the sun sets – it rushes to where it rises again the wind blows round, round and round – it stops, it blows again all the rivers run to the sea, but the sea is never full – from where the rivers run they run again these things make me so tired – I can’t speak, I can’t see, I can’t hear what happened before will happen again I forgot it all before. I will forget it all again. ~ again (after ecclesiastes), David Lang, 2005 The Hebrew Bible is composed of three sections: the five books of Moses, the Prophets, and the Writings. It has the same books as our Christian Old or First Testament but they are ordered just a bit differently. While all these texts play a role in Jewish worship, five books from the Writings are associated with and provide structure for Jewish holidays through the year. The scriptures have, in other words, a liturgical function, charting the course of human experience through the year and from one year to the next in the midst of the assembly. The deeply philosophical book of Ecclesiastes provides the context for Sukkot, the feast of booths or tabernacles, a harvest feast that occurs in the first month of the civil year (usually September or October in our calendar). The book is read aloud in some synagogues as a part of the celebration. Sukkot, then, is both end and beginning in the yearly cycle of Jewish worship. The modern composer David Lang was struck by the linkage of Ecclesiastes with a fall harvest celebration. In his notes on his 2005 piece titled again (after ecclesiastes)—performed to powerful effect by the Northwest Chamber Chorus this season—Lang reflects: “Somehow it seemed very poignant to me that Judaism might link together such a dark and philosophical text with a joyous religious festival celebrating abundance.” He embraced the idea that these celebrations, like our own Christian celebrations chart a cycle of celebrations that move us from one year to the next. They underline the breadth and depth of human experience. Lang again: It seems to me that the point of connecting each book to its holiday is that these books are very human, very personal. Much of religion is mysterious and unknowable, but these books are all about people and their emotional lives – life and death, courage, love, companionship, regret. His complete work the writings, written over the course of 14 years, reflects this awe-inspiring cycle of human life and human emotion. He begins and ends with the movement again (after ecclesiastes), yet the score “instructs the performers to sing it differently. The cycle, like the year, may repeat, but never exactly.” How does a weary world rejoice? I would guess soul by soul and day by day. But if you ask me, I bet most of it counts. ~Sarah A. Speed @writingthegood, December 4, 2021 How does a weary world rejoice? We allow ourselves to wonder at this world, at this human experience, at the ebb and flow of loss and gain, death and new life. We allow ourselves to be amazed. And like old Zechariah and Elizabeth, it may change us forever. Enter into worship this Advent Sunday. Readings: Isaiah 61:1-4, 8-11 † Psalm 126 † Luke 1:57-66 About the art: What Wonder Turns Into. Lisle Gwynn Garrity. Acrylic painting on canvas with digital drawing. Inspired by Luke 1:57-66. Used by permission.

From the artist:

When was the last time you were truly amazed? I don’t mean surprised; there is much about this world that should shock us. I mean amazed—wrapped up in wonder, absorbed in an unexpected delight. I love witnessing the moments when my one-year-old daughter allows amazement to wash over her like a gentle rain: her jaw drops open, her eyes widen and stay fixed, and for a rare moment, she gets very still. This recently happened when she discovered the kids across the street playing basketball for the first time. Her senses have not yet grown dull to the magic surrounding her. In this image, I wanted to capture the moment Zechariah’s voice returns to him. I decided to depict only half of Zechariah’s face; this miracle is not really about him, but about what happens through him. When he confirms John’s name, he sheds his distrust of the angel’s impossible news. His skepticism and weariness subside as he awakens to the joy in his midst. He allows himself to be amazed. Zechariah’s voice pours out of him, parting the surrounding crowd like the Red Sea, stirring each person into confusion and bewilderment. The blessing of his song spills over to his son, who is held tenderly by his mother. Elizabeth is the only person in this scene who is not presently swept up in wonder. I believe Elizabeth has spent months allowing herself to be amazed. She was in isolation for the first five months of her pregnancy (Luke 1:24). Perhaps she needed that time to go inward—to heal from the trauma of her infertility, to trust the promise of life in her womb, to attune herself to her child. She was capsized with awe the day Mary showed up at her doorstep. And so, when Zechariah’s voice returns, Elizabeth’s senses have not grown dull. Instead, her amazement has metabolized into something new: attunement for her child. It has transformed into love and deep trust. It has turned into joy. When we allow ourselves to be amazed, we might be surprised what that wonder can turn into.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

worshipYou'll find here links to weekly worship and, where applicable archived service videos. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed